The transcendental imperatives to “love thy God” and to “love thy neighbour” are ethical maxims that undercut the immediacy of political thought—they are impossible through the mode of politics (the political agent neither acknowledges nor recognises the neighbour due to their objectivity), therefore to act politically is to act against—or, at very least, indifferently towards—Christ’s commandments. It is to relate relatively to God and to relate absolutely to politics.

The Christian Politician—an oxymoron

I have given them Your word; and the world has hated them because they are not of the world, just as I am not of the world. I do not pray that You should take them out of the world, but that You should keep them from the evil one. They are not of the world, just as I am not of the world. (John 17:14-16)

I. Christians are not of this world. But what does it mean to be not of this world? It means to be opposed to this world in its immediacy as “the evil one” and instead be present in the Body of Christ in transcendence—eternally and necessarily. As the world is contingent and is necessarily contingent, it can only ever offer contingent solutions to contingent problems; Christians, capable of rejecting the ressentiment of contingency, are not of this world.

II. If Christians are not of this world, does that mean that the world’s interests are incompatible with Christ’s? No, not necessarily—only aesthetically. As the world is contingent and necessarily contingent contra God’s necessity, we find that the world is not capable of grasping either the “reason for” or the “in order to” that provides action and belief with their objective value. When those of this world are interested (Inter-esse) in acting in a way which is aesthetically similar to Christ’s interests (Esse), they appropriate His message into their own “reason for” and “in order to” as an attempt to grasp authority from the authority of all authorities—fundamentalists, Social Gospelers, Christian nationalists, Christian communists, etc. are all guilty of taking Christ’s interests (Esse) as equivalent to their own interests (Inter-esse), reducing the necessary to the contingent and turning the contingent into a false authority to wield against those without eyes to see or ears to hear.

III. If Christ’s interests are not like those of the world, does that mean a Christian’s interests are identical to Christ’s? Not necessarily—potentially, not at all. As the Christian is immediate and Christ is both immediate and transcendent, there is an essential and contradictory difference between the two; from this position, the “criteria of verifiability” hangs over us: how would we know if our actions are at one with God? Do we hope for fantastic revelation at every turn? Do we hold to the fantastic subjectivity of the Quakers and insist that all perceived episodes of the Spirit’s intercession are episodes of the Spirit’s intercession as such? No, such a position is tantamount to the rejection of God’s existence as transcendent and our existence as immanent; it is the assertion, as such, that what I desire to be God’s will is God’s will, despite holding no “criteria of verifiability” concerning the transcendent that can be understood from within the immediate. It is the misunderstanding that, while “subjectivity is truth”, subjectivity is, by its nature in the wake of the fall, “untruth”1. To speak of a fantastic unity in mysticism is to speak as if one’s interests (Inter-esse) are essentially Christ’s interests (Esse)—it is to speak as if not only is it possible to become Christ-like, but Christ again.

IV. If Christians are not necessarily at one with Christ, does this mean that they can have essential knowledge on how to deal with the world? In part, but not necessarily—the impossibility of the imitatio is not a cruel joke on humanity, a piece of divine mockery given to the sinner in their sin; it is a guide, a “grammar”, a way of living that becomes unfolded through a life lived in pursuit of faith. Much as a child learns to love their parent in growing to understand them as who they are and not necessarily what they are, the Christian must learn to be like a child again in accepting that the Truth is not that which can be imposed upon the world in order to bring about some contingent end qua “demand of the times” from secularity imposed upon the Body of Christ—the Truth is a who and only in knowing that who can we become free in the relationship of freedom.

V. As such, the Christian does not know how to rule—he only desires to be in a relationship. The fundamentalist, the Social Gospeler, the Christian nationalist, the Christian communist—these do not appropriate Christ into their lives in their political bludgeoning; they colonise Him, export His goodness into their immediacy, and turn to the world with a vengence. The Christian is first aware of the joy—the joy!—in the thought that against God, we are always in the wrong.

The Problem of Christian Politics

Christians are both “not of this world” and also within the world, a popular piece of wisdom that is often shared as if it were scripture itself. This brings about a great many issues for understanding how Christians should interact with the world, how they understand their sin, and how they react to challenges which seem to push them towards sin—something that sits at the root of a Christian approach to politics and society in general, but is often missing from the most earnest and fanatical of accounts. This is why the arkys-faith of the fundamentalist, the Social Gospeler, the Christian communist, the Christian libertarian, etc. all collapse into simulcral reflections of their contemporary societies, i.e., “the world”—because they start from a position where their faith is the start of all faithful actions, because they start from immediacy. The political action of the Christian who attempts to think immediately about God’s good actions in the world, discontented by the apparent inefficiency of the Lord’s saving works, will become an amusing slush of anti-theological theology, where apparently all of scripture points towards workplace democracy, the minimal state, government-mandated fertility programmes, liberal human rights—and so on, into the neverending slush of secularity stamped onto the received Word of God. It seems, to the naive eye, that God’s decision to create humanity in the flow of time as contingent beings has undermined any possibility that we have for asserting a Christian faith into “the world”, i.e., our lives as immediate beings cut off any possibility for us being otherwise at all.

However, this is not necessarily the case.

A most curious ontological argument

Theologians have often thought of themselves as philosophers—for Augustine and Thomas, this meant the heroic illustration of the faith that allowed for Christians to talk intelligibly about what God has given them in every good and perfect gift to creation (James 1:7); sometimes, as with Descartes and Hegel, this has been the instrumental use of the divine before dismissing His glory as an inconvenient or noncognitive factor to a genuine understanding of reality. Along the way, a variety of arguments have been offered as to why it is rational to believe in God, i.e., how the immediate can understand the transcendent. While this throws up a wealth of philosophical problems that we do not have the space to explore here (and, indeed, we ought to explore them in the way of dismissing the kind of thinker who takes Hegel, Spinoza, or the Stoics as individuals worth quoting), it does lead us to an essential problem for the faithful: how on earth could we even hope to understand God’s transcendent being and becoming if the transcendent is beyond the realm of human experience? When our lives are so fundamentally based on the way we see the world around us and shaped by what is available at any given time, would it be even possible to understand the divine in a way that makes it possible to follow?

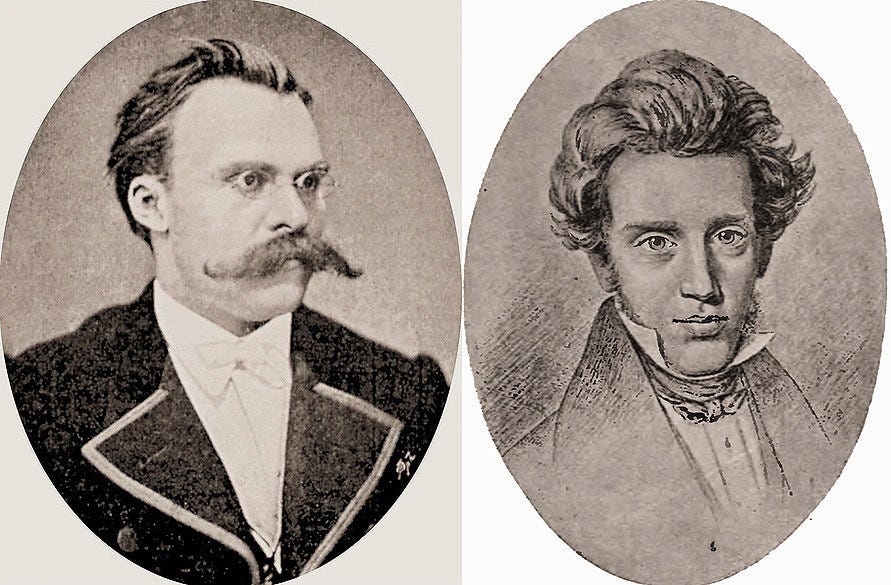

Here, a sceptical Danish thinker offers a sketch of an ontological argument that explains what he sees occurring in the life of the believer:

The idea of being helped by the god to come into existence—to be reborn—can have come only from the god incarnate in time; that is, the idea of coming into existence or being reborn could not have occurred to the one who has not yet come into existence or who has not yet been, and thus does not know what it means to be, reborn;

I have indeed come into existence;

Therefore, God necessarily exists.2

This, presumably, looks quite confusing at first glance. However, this will be key to understanding who these Christians are and how they act in the world.

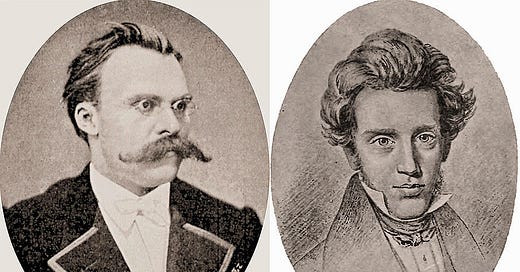

Starting from the life of the believer, there was, at some point, this event, this “quickening” in their life, where they were “born again”—a primitive experience where the glory of God broke through into the individual’s understanding and made Himself known to the one who would know Him. It appears, then, that this choice to recognise the self as being “otherwise than it was”, i.e., being “born again”, is central to any real Christian epistemology—for our purposes, where one has chosen to believe that there is no longer mere immediacy in their understanding, but also transcendent knowledge that pulls our understanding of the world first into incoherence and then into piety. Contra later thinkers like Nietzsche and Sartre, this view of the “radical choice” is rather unradical, though: for the “existential thinker” who radically leaps into the blackness of an unknowable future, their choice to leap is merely based upon their desires to be as such; there is nothing which upholds this choice aside from their particular way of being in the world at that particular moment.

Many people have no real problems with this—why wouldn’t I act in accordance with my desires? I desire them, therefore, it makes sense for me to satisfy those desires! For the aesthetic thinker, for the one trapped in immediacy, this presumably seems like a reasonable enough response for why someone might desire to do any particular thing or any other particular thing. It is a step into authenticity, an earnest choice where one chooses themselves over others and prioritises this genuine understanding of the self over other aspects of their lives. However, what grounds this choice? What makes this “radical choice” a choice which is radically correct for the chooser? Concerningly, there is not only the error of being absolutely related to the relative but also absolutely relating to the relative in the misunderstanding that it is an absolute relation to the absolute. We see that another Kierkegaardian pseudonym, seemingly in prophetic proclamation, turned the sword to Jean-Paul Sartre:

“But with the help of the infinite form, the negative self, he wants first of all to take upon himself the transformation of all this in order to fashion out of it a self such as he wants, produced with the help of the infinite form of the negative self... he himself wants to compose his self by means of being the infinite form.”3

The “radical choice” is the last gasp of desperation, the earnest cry for the gods to reach down into the fallen husk of Christendom and save humanity from their condition—the secular thinker, standing over the corpse of liberal theology in the early 20th century, looks around him and finds that there is no meaning for anything, no reason to go on, no grounding for his assertions. A haunting piece of scripture creeps up his spine as he remembers Micah’s weeping: “You took my gods that I made and my priest. What do I have left?” (Judges 18:24) This thinker finds their anxiety finds no rest, no terminus, in life and merely creates new questions that are each as unequally answerable as the each of the last.4 In his aesthetic movement, he springs from one saviour to the next, determined that this time, with this spring, there is truly meaning in this “radical choice” that gives his life his meaning that he will not reject when his aesthetic sense pulls him away again.

This desire is the desire to end all desires, this purpose is the purpose to end all purposes!—until it isn’t. The “radical choice” is exposed—in the flow of life, there is no radicality to this choosing, but only the impotence of an anxious thinker who finds themself straddled in the crashing wake of reality. Without his ballast set in a way which allows him to understand the world around him, he crashes into rock after rock—all the while captured by this explosive force of reality that, just as quickly as it appears and becomes the Pseudo-Petros on which his life shall stand, disapates in the flux of life.5

S. K. is not so groundless—although his scepticism carries him out over the “70,000 fathoms of the deep”, where no man treads as if he has found himself there through some internalised Babelic structure which resists the calling of the Cross.6 Instead, we notice that this ontologist offers us something slightly different: instead of the “radical choice” being based upon the ephemerality and nothingness of our desires, it is based upon this unmistakable, life-altering realisation that one has been “born again”7.

While many a great theologian attempted to usher in the “age of man”, where he could walk without the confines of religion in the simple pursuit of faith8, a certain Dane smiles from eternity at the idea that this possibility had ever not been granted after the saving grace of Jesus Christ—it was always possible to choose freedom in a way that matters through a “radical choice” that is only radical inasmuch as it sees the human agent “as he is” in the eyes of the Lord9. Or, to dress it up in all the more elaborate philosophical language, the choice rests not on the volitional immediacy of the individual but rather this transcendent ontological state of the believer in their belief. Think back to our argument: the recognition that one has ontologically changed can only have come about through the intervention of One Who understands the difference between immediacy and transcendence, yet no person can do this; if there is any truth at all in the claim that Christians can, indeed, be “born again”, become “a new creature” (2 Corinthians 5:17), then this realisation can only have come about through the individual realising that God has not only intervened in their life but also made it known to them that there has been an intervention—otherwise, there is no grounding for this assertion and Nietzsche presumably sounds like a keen interpreter of the will and not merely a sick man playing in the creations of imagined “past as present”10.

Transcendence, this real realisation that we are “new creatures” that could only come from God, then, becomes known to the immediate only through Øjeblikket. “The instant” or the blink of the eye, not in the sense that one closes their eyes to the world, but rather in that one’s eyes are finally opened to reality11. In this sense, the universality of Absolute Truth qua God’s self-revelation to humanity only comes through the individual in their particularity—the radically personal empirical evidence of God’s intervention in the life of the believer as the death of Adam and the rebirth in the Body of Christ with open eyes to see and open ears to hear. This idea of radical intervention by God is very much a taboo for intellectual conversation in the modern day; such unverifiable, subjective evidence is tantamount to mysticism and the opposite of the very Enlightenment values that we hold tightly in our attempts to understand the world around us. Appeals to “radical empiricism” seem like a silly way of proving anything to anyone, especially in the condition of our natural and necessary subjective separation.s. Evans illustrates:

“Imagine an individual who has come to believe, perhaps by reading Nietzsche or Ayn Rand, that compassion is in fact a vice, and that truly ethical people care only about themselves. Despite this objectively wrong belief, it might be possible for this individual to respond with genuine compassion and love when confronted by actual human suffering. Whatever the ultimate ethical and religious truth may be, human persons may be better—or worse—than their theories. The Kierkegaardian view is that it is subjectivity, the inward emotions and passions that give shape to human lives and motivate human actions, that makes the difference.”12

In short, it is an attempt to demonstrate to the other what can only be known to the self—but, as a possibility, it may be recognised by its fruits13.

For what it is worth, S. K. would agree still agree with that critique that this is no proof for the existence of God—the figure who proposed this semi-ontological argument was not “S. K.”, as such, but rather Johannes Climacus in Philosophical Fragments. Having stood outside the body of Christ, attempting to understand the what of Christianity as an object of science instead of understanding the who of Christianity as Christ’s figure of Truth1415, he fails to make that leap into faith where it is possible to understand the light of God’s revelation when it is grounded in one’s relationship with Christ; but who are these people that stand on this unsteady ground, contra Climacus, contra the Corinthians?

The truth, it appears, is that the ground of this faith is found not in some creed or doctrine—rather, it is found in the earnest realisation of the God-relationship, the recognition that the truth of this world is a who that wishes to love and be loved by us16. To begin to think as Christ’s follower is to begin to see the world as it truly is: nature, overflowing with the divine love of the who that is Truth.

“The realist rightly holds that the particular is nothing except as the expression of an idea, and the nominalist rightly holds that the idea is nothing apart from concrete realization. A pure particular, without any universal element, would disappear entirely from thought; and a pure universal, with no local habitation or name, would float in the air without contact with reality. There can be no living experience without both elements, and there can be no experience apart from an immanent intelligence.”17

Ontology, not Identity

“The claim that we love because God first loved us suggests that even in cases where its particular manifestations are not merited, precedented, or reciprocated, love is a reasonable and reciprocal response to the world’s pre-existing and indeed fundamental condition.”18

Identity politics is both a constant danger to Christians and the opposite of Christianity itself. In an aesthetic sense, there is a parallel to what we have already discussed and how this radical self-affirmation or collective-affirmation for the church polity structure leads onto the singular barb in the side of the enemy and the collective expression of power that proceeds from the polity expressing itself within reality. Without our desires ruling over us, it appears that Christian movements which attempt to engage in politics instantly collapse into the identitarian mob rule of the nihilism that we attempt to stand against. If there was ever a clearer case of this, American politics over the last twenty years seems to be a suitable example that “faith”, or, at least, the use of that word which finds no reflection in reality, can be used to justify anything and everything when it is said by the correct mouthpiece to the correct audience.

Identitarianism is rooted in the individual’s or the collection of individuals’ “radical choice” to view history in a particular way. As all good things, secularity and critical theorists in particular discovered the great Christian tradition of hermeneutics and quickly set it to task—however, without the grounding of the church (as a lesser body for maintaining order) or the Body of Christ (as a greater body for seeing humanity struggle in its impotence), these mechanations quickly turned into a fight over history for the rights to call oneself the true Messiah, the true innocent sufferer in the face of “the world”. By adopting the subjectivity of “radical choice”, these eminent scholars quickly become the facile reflections of their reactionary and conservative adversaries in that they adopted an aestheticism of comforting subjectivity19, a cudgel sub specie aeternitatis by which to beat their interlocutors and, when it becomes convenient, their allies. The identity is adopted in order to hide from the overwhelming realness of reality, the horrific exposure to “the Sublime” wherein one realises one’s finitude and temporality. As all bad radical philosophy, it doesn’t take long to identify the Epicurean root in their thought that exposes a constant terror of death, a constant terror of being forgotten by history—their hermeneutic justifies their struggle as it is all they can amount to. Trapped in immediacy, their “radical choice” justifies the sideways movement of the panicked aesthete, much like the character “A” in Either/Or.

No, this will not do. The Christian cannot collapse into this “radical choice” because, above all else, these commitments to choices amongst choices are already admissions that there is no such thing as being “born again”, no ontological change in the life of the believer, no freedom in Christ. But how do we escape this knot where our universal claim in our particularity can collapse into odiously non-Christian pursuits such as concerns over “falling birth rates” or “abolishing taxation”?

“In other words, we need the religious, as transcending the ethical, to prevent the ethical from collapsing into uncritical social conformism.”20

As Abraham understood, stood atop the mountain with dagger in hand over his beloved son, faith cannot be merely reduced to the particular choice of a perspective and an adoption of some ethical stance or other, we must be prepared to venture out into the unknown, over the deep, when the time comes for us to affirm that we are saved by faith and faith alone—even in those times where reason cannot provide us the ground on which we desperately wish to stand. Indeed, faith is a leap from one sphere of life, where meaning proceeds from our deeply held ethical convictions about how the world ought to be, to another, where we base our desires in the calling of the Lord; we are called to the kerygma and must be prepared to break out of our particular “reasons for” and “in order to” when it becomes apparent that our contingency in this contingent world is out of line with the necessary that proceeds from God’s will necessarily.

This is that which cuts the Christian off from identity politics when they learn to act “as they are” in being “born again”: we find it, but may mistake it, in the aesthetic unity but the religious opposition of the “radical choice” and the ontological realisation of Øjeblikket. Only those who now understand that they see the transcendent before them, that they are spilling over with love from the Lord that must find an object in reality, will be able to discern the identitarian from the Christ. Only those with “open eyes” can see what God wishes for the world, but all those with “open eyes” are also those who are trapped by their immediacy. Only those who have indeed begun the ontological task of “ethics as first philosophy” will be able to rise out, over, and against the received wisdom of secularity through the earnest refusal to take power and use what is not theirs. To do otherwise, to pretend that we can take this “God’s eye view” of reality as if we were the total conduit of the Lord on Earth (Christ Himself—again!) would be to deny our immediacy and falsely claim to have become some sort of transcendent begin that walks the Earth. For such people, presumably only a chuckle can ever be mustered against their ranting and raving, as it could only ever be a joke or a serious misunderstanding.

“The difficulty of authentic subjectivity, it turns out, is not in transcending the world, pushing oneself up to greater and greater heights; rather, the praiseworthy achievement is in how one brings oneself down.”21

An error here would be to assume that Christians hold some special key to help unlock the truth of reality and set humanity free into a new age of prosperity and accord. While noble in their aims for this world, the Social Gospelers are a prime example of this: if only the world could hear the proclamation of the Lord in the good deeds of the faithful, the world would come to be as good as Creation was intended to be. Of course, what happened here was that “the world” gnawed away at the message of the Social Gospelers until their work was reduced to little more than a meek whisper of approval for the genuinely successful work of their contemporary, secular, social-reforming contemporaries22. Even worse, we find the faithful often thrown from pillar to post by the political demands of a figurehead, “the one”, that displays all that is necessary for their piety through an offhand remark to the “special interest” of a particular interest group or a vague allusion to some snippet of theological concern. The pitiful excitement around “raising the birth rates” amongst a certain type of the faithful in the past year, for example, shows the complete ungroundedness of their theology and the delight with which they are whipped up into a furore (especially in the context of 1 Corinthians 7:8-9—Lord forgive a sinner like Paul). So, then, our position cannot be as a “civilisation mission” to the world23, an assumed position of authority over the unwashed masses that views them with contempt and tolerates them in their failure; the world that they live in is the same world that we live in, therefore we are pulled between the two kingdoms as a light in the dark and an ekklesia in the world. It is not a world beyond this world, but a mode of thinking beyond reason; our “epistemic humility in our encounter with reality.”24 Instead, it is an earnest admission that Christians do not know how to rule the world as this has not been revealed to them: “the world”, of course, is the opposite of the Christian, it is the assertion that one has no need for God and no need for God’s methods. This position of humility, this humiliation before the Lord in our finitude, then, is the first step towards a politics of indifference that sits paradoxically with “the world” and seeks to draw all unto us as Christ draws all unto Him (James 4:8).

A Politics of Transcendence

We have staged the challenge: a Christian politics cannot come from immediacy as God and God’s will is not merely immediate but immediate and transcendent. The paradoxical reality of our foundations means that we will fail to offer arguments that the one who doesn’t know Christ, that doesn’t see transcendence, could understand; indeed, our distant relation to that transcendence, then, means that we are not necessarily unbiased interpretators of what it best for us to do. The threat of immediacy is twofold: first, in risking the collapse into identitarianism that leaves the believer to grovel at the foot of the state in forcing the world to do their will; second, in exposing that our desires for God’s will to be as such are often taken to mean that our desires are God’s will. Neither position is defensible for the Christian on multiple counts and requires us to develop a new platform for political action that recognises the peril we find ourselves in.

Firstly, then, we start with the individual: the person, loved by God and aware of the transcendence gifted in being “born again”. This person, as a missionary to the world, is tasked not with giving the world a set of moral dicta that it must adopt at a distance. For this Christian to judge the world is not only to distrust that which is revealed to us in the Word of the Lord (Matthew 7:3) but also to expect the other to act in a way they cannot understand. If our “form of life” springs from this realisation of revealed transcendence, how can we expect the immediate to follow that path when they could not possibly understand it? Note, now, that the Christian is called to offer God to “the world” in the loving call to love thy neighbour, all neighbours, first and foremost—because, if God is love (1 John 4:16), then to love the neighbour as we love God is to offer God to the unbeliever in the hope that they may glimpse Øjeblikket. The centrality of the person here is due to their nature as a subjective being: “[subjectivity's] very first form is precisely the subtle principle that the personalities must be held devoutly apart from one another, and not permitted to fuse or coagulate into objectivity. It is at this point that objectivity and subjectivity part from one another.”25 This process is interpersonal and set of the triadic relationship that one holds Christ close as the Mediator for “the world” in its sin; something that is impossible for the impersonal, aesthetic movements of the political actor or the tone-deaf moralism of the ethical identitarian. As we are “born again” and see that it is possible through God that all things might find him, ethics and politics must then start from the position that the person opposite us, mediated by the love of Christ, is capable of turning to God through their own free choice that accepts the prevenient gracious gift of faith.

Secondly, we must also be prepared to admit our error in “the world” as we are neither on a “civilising mission” to teach “the world” how it ought to be nor “the Professor” who sits outside the flow of reality and judges it as an object of our science26. Indeed, to imply our expertise over how creation ought to be, paradoxically, ends in us denying our immediacy. No, we have been offered the tools to bring about the change that matters in this world: first, by finding the love of God; second, by showing that love of God to the neighbour; and third, by bringing the church into an age where it is the church proper, sojourning and missionary in character, not triumphal in its belief that anything it has to say represents anything that eschton will.

Thirdly, our opposition to worldly politics should sit in the basic understanding that Christians, in glimpsing transcendence, are aware that there is something that “the world”, in its opposition to Christ’s message by erecting the cross, will never understand. This is not a call to quietism nor a call for the collapse of Christian involvement in the world—it is the very opposite. It is the call that Christians, first and foremost, become aware that Christ’s message is not of this world and, therefore, “the world” must learn its message first through the light of the Lord shining into creation. And what is the fundamental fruit of that message? In the simple display of will that the one to whom I have a duty is my neighbour, and when I fulfil my duty, I show that I am a neighbour. Christ does not speak about knowing the neighbour but about becoming a neighbour oneself, about showing oneself to be a neighbour just as the Samaritan showed it by his mercy27. While the dead in spirit fail to see creation “as it is”, seeing only the dead matter through eyes that can only see “the real” from within contingency, and lack the humility to admit that only through the eyes of the Lord can we understand creation in full. They are, it appears, absolutely related to the relative. As the politician, in their faux-theological structure of the state, must rule over creation as if they had created it, they lack the proper perspective which gives us the mode for understanding it “as it is”.

“In many ways the Church Fathers’ descriptions of demons fits the politicians of our day. They lived in the air (they are far too windy to be able to keep their feet on the ground); they lived on the smoke of offerings and incense; they were very mobile and could pass over the whole world in a hurry.”28

All they can assert is “as it ought to be”, with no grounding for that ought to be found. To emerge from “the Crowd” contra political power is to become Hauerwas’ character, to become spirit before God in the joyous responsibility to God and the neighbour in love. For those who can stand this demand and the judgement that comes with it, the joyous idea that one could be judged by the all-knowing in the highest court of all29, is to become a Christian.

Fourthly, I turn to the words of Karl Barth, for the strength to understand that one’s actions cannot change the world in even one iota (Matthew 5:18):

“But keep your chin up! Never mind! He will reign!”30

An honest admission that, despite the pessimism that this world brings us to, we are optimistic about all the value it already has. To say this in earnest, despite how the world is, truly does reach S. K.’s insistence that the Christian message will always sound like “the most profound sarcasm, but genuine nonetheless”31.

For more, follow the links below:

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 207, [J. Climacus], tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

“Between Kierkegaard and Descartes: faith, reason, and the ontology of creation”, A. Kulak, from Inscriptions 4, no. 2, p. 131

The Sickness Unto Death, p. 244-245, [Anti-Climacus]

The Existentialists and God, p. 9, A. C. Cochrane

“Kierkegaard: Father of Existentialism or Critic of Existentialism?", p. 19, C. Stephen Evans

Works of Love, p. 363, S. Kierkegaard

Heidegger and Kierkegaard, p. 28-29, G. Pattison

E.g., Bonhoeffer: “God would have us know that we must live as men who manage our lives without him. The God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34). The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God and with God we live without God. God lets himself be pushed out of the world on to the cross. He is weak and powerless in the world, and that is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us.” Letters and Papers from Prison, p. 360, D. Bonhoeffer

“Kierkegaard's Metatheology”, T. P. Jackson, from Faith and Philosophy, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 83

“Envy as Personal Phenomenon and as Politics”, R. L. Perkins, from International Kierkegaard Commentary, vol. XIV: Two Ages, p. 130

Heidegger and Kierkegaard, p. 29, G. Pattison

“Kierkegaard: Father of Existentialism or Critic of Existentialism?”, p. 14-15, C. Stephen Evans

Works of Love, p. 14, S. Kierkegaard

“Paul and Kierkegaard: A Christocentric Epistemology”, H. B. Bechtol, from The Heythrop Journal 55.5 (2014), p. 942

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 203, [J. Climacus], tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

“The Inviter” in Training in Christianity and the Edifying Discourse which 'Accompanied' It, p. 41, [Anti-Climacus], ed. S. Kierkegaard

Personalism, p. 119, B. P. Bowne

“Anabaptist two kingdom dualism: metaphysical grounding for non-violence”, C. Zimmerman, from Religious Studies, p. 4

Carl Schmitt's Critique of Liberalism: Against Politics as Technology, p. 48, J. P. McCormick

“Kierkegaard and the Critique of Political Theology”, A. Rudd, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, p. 24, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

“Downward Bound: the Knight of Faith and the Politics of Grace”, H. C. Ohaneson, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, p. 65, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

“On Keeping Theological Ethics Theological”, from The Hauerwas Reader, p. 66-67, S. Hauerwas, ed. J. Berkman and M. Cartwright

“How “Christian Ethics” Came to Be”, from The Hauerwas Reader, p. 49, S. Hauerwas, ed. J. Berkman and M. Cartwright

“Common People: Kierkegaard and the Dialectics of Populism”, from Argument: Biannual Philosophical Journal 11(1), p. 180 R. Rosfort

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 73, [J. Climacus], tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

“John Alexander Mackay: The Road approach to Truth”, M. Alessandri, from Kierkegaard's Influence on Theology - Tome II: Anglophone and Scandinavian Theology, p. 78

Works of Love, p. 21, S. Kierkegaard

Quoted in The Controversial Kierkegaard, p. 3, G. Malantschuk

Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, p. 69, C. Constantius/J. Climacus, ed. M. G. Piety

Karl Barth: His life from letters and autobiographical texts, p. 498, E. Busch

“Thoughts That Wound From Behind - For Upbuilding: Christian Addresses” in Christian Discourses, p. 232, S. Kierkegaard