Absolutely relating to the Absolute

To reject relative means towards relative ends

Before we start, be sure to consult the position we critique here:

To move beyond the problem of absolutely relating to the relative, we must first emerge from the cave through a relative relation and then into a proper absolute relation. This, presumably, sounds wonderfully esoteric at this point. However, as Rudd’s terming of the entire Kierkegaardian corpus as “Platonic Realism”1 removed the scales from my eyes, we should understand S. K.’s overall mission to remove the scales most stubbornly unremovable—the scales that only the offence2 could lift. We might consider S. K. a mystic of sorts, but only inasmuch as the architect or the mechanic who “sees” construction and cars in a way that the non-architect or the non-mechanic cannot; only by having crossed the threshold into faith can one recognise the demarcation between “this world” and “not of this world”. The movement from a relative relation to the absolute relation to the absolute views the Anselmian fides quaerens intellectum not as a simple want, but the boundary of a genuine ontological change in the life of the believer.

Relative relations and the absolute

All relations are either absolute or relative—if we are not committed in full towards some particular thing, then we are related to it relatively. This is not a moral note, but merely a metaphysical one; there is no necessarily moral problem that arises from relatively relating to aspects of the world around us, especially considering that i) we—due to our finite nature—have a finite amount of time in this world and, therefore, must make priorities about how we intend to spend our time amongst the living, and ii) as a fact of our temporal existence, there are certain demands that conscious existence forces onto us in the way we relate to the world around us. In short: we don’t have infinite time to relate to all things and that finite time requires us to prioritise. Hopefully, at this stage, our assessment will not be too controversial or psychologically speculative.

As we have covered elsewhere, these relations have serious implications on how we interact with our social reality, the Hegelian Sittlichkeit3. There are certain facts of our social world which mean that particular worldviews are expected of the individual and collections of individuals within any given society and there is a level of relativism in these social exceptions—S. K., anticipating a world that could no longer hold to grand narratives, doubted the Hegelian confidence in a Whiggish understanding of history as constantly developing, always progressing towards some form of the Ideal4. These “relativisms” exist across two axes: i) socially, by which I mean that different communities will exist relatively to other communities in the particular values they hold as more or less important, and ii) temporally, by which I mean that “travelling through time” delivers us into different epochs, different “given actualities”5, that bring with them different ways of thinking. In this sense, we recognise the role of ideology, much as the Marxists have done so thoroughly in the past; however, we do not pretend that we are capable of stepping out of these temporal spheres.

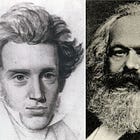

Much like Hegelianism, many Marxists have viewed the temporal reality they exist within to be “a step along the way”, an inevitability, towards the Platonic form of society. To some extent, we might also view certain anarchist thinkers of this glassy-eyed utopianism as well—most notably, the anarchist prince Pyotr Kropotkin. In truth, this Hegelian understanding of social change is not a higher understanding of reality, but an aesthetic, detached, and concerningly objective understanding of reality as “[a]esthetic individuals either relate relatively to an absolute or relate absolutely to what is relative.”6 The perspective is itself only a reflection of the period it emerged from in that presupposes that, like all things(!), we can provide a rigorous and “scientific” mode by which to understand it. As Ryan notes in his reflection on S. K.’s ironic relation to his German contemporary:

“Shortly before the revolution of 1848, Marx and Kierkegaard lent to the demand for a resolution a language whose words still claim our attention: Marx in the Communist Manifesto (1847) and Kierkegaard in A Literary Review (1846). The one manifesto ends “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” and the other to the effect each person must work out his own salvation, prophecies about the course of the world being tolerable only as a joking matter.”7

In short: the Marxian prophecy is an inappropriately confident prophecy that we simply can’t take on any level of assurance. Perhaps we find its bold, sabre-rattling rhetoric inspiring and even convincing within our epoch—however, there is no reason to believe that humanity has learned the secret of constructing rational proofs that provide us with the intellectual equivalent of divine revelation. But, this does not mean that a particular will cannot be directed to understand the divine:

“Then came 1848. Here I was granted a perspective on my life that almost overwhelmed me. The way I saw it, I felt that guidance (Styrelsen) had directed me, that I had really been granted the extraordinary.”8

To bring this back around to the matter at hand, my reader, the leap from the aesthetic to the ethical here is not a change in the information we hold, but rather the perspective from which we approach the information—the aesthetic, as a locus of existence9, is no longer related to absolutely, but relatively; it is not held as the absolute value or “first object” of our thought, but rather as something which we can draw upon as appropriate in relation to a different “first object”.10 And, in absolutely relating, we have chosen to make use of “the extraordinary”.

Absolutely relating

In an effort to avoid boring you with winding prose, my reader, I won’t repeat what I have written elsewhere on the difference between the absolute relation to the relative and a relative relation to the relative. You can read that here:

As explored in that piece:

What does it mean to relatively relation to politics and still take Christian political action that is absolutely related to the absolute? My reader, I leave you with an insight from Bartholomew Ryan:

“The concept indirect politics is not multi- or trans-disciplinary because it is a negative space within each discipline; it is inter-disciplinary because it nevertheless demands attention from those disciplines by asking them to rethink themselves.”11

It is not enough to simply state that we have moved from absolutely relating in a false way to relatively relating in the proper way to relative matters. When we have world negated the world around us absolutely, we hold a merely negative relation to the absolute12 as well as the rest of reality—we lack faith still, we lack the absolute choice. This would lead to the often caricatured, even more worryingly often actualised faith of the “hyper-Calvinist”; fear and trembling in relation to an empty concept13, either a total imagining on the part of the individual or an enforced social contagion objective to the individual. We would simply become nihilists: the enemy of the Christian anarchist.

This raises two problems: firstly, that we are no closer to actually finding the absolute to which we will absolutely relate; secondly, that we are merely reflective and sceptical. We exist objectively in relation to reality, therefore we have collapsed through the existence-spheres into aestheticism—and we’re back where we started. Much like the utilitarian, we will pretend that we are actually discussing something that might affect someone’s life and instead become content in faux-calculations and self-applause—neither hot nor cold (Revelation 3:15-16), we are indifferent to reality. Nihilism.

…in faith

To overcome this, we must turn to the most fearsome characters in the Kierkegaardian oeuvre. The flighty Johannes Climacus begins:

“[The subjective thinker] is conscious of the negativity of the infinite in existence, and he constantly keeps the wound of the negative open, which in the bodily realm is sometimes the condition for the cure. The others let the wound heal over and become positive; that is to say, they are deceived.”14

The infinite here, my reader, is the very thing which distinguishes the religious believer from the unbeliever—or, rather, the relation to the infinite, the expression of the infinite, the realisation of infinite possibility in the life of the who simply believes is that very point of ontological difference; like the difference between a child and an adult, there is a distinct difference between the way the Christian ought to see the world if we genuinely believe we are gifted something with the gift of faith.15 We hold it, like a child holds a special stone of no particular note to anyone else: “God is infinite wisdom, what the human being knows is idle chatter: therefore they cannot very well talk with one another.”16 Climacus notes that the subjectively existing religious individual is not someone who merely relates to their faith as an “object” to them, i.e., they have internalised outward signs of religious life into internally meaningful and passionately held principles that guide the way one lives. Without this personal devotion towards faith, we descend into a “crudeness” that blocks our very ability to be genuine selves at all:

“...in the world of individuals. If the essential passion is taken away, the one motivation, and everything becomes meaningless externality, devoid of character, then the spring of ideality stops flowing and life together becomes stagnant water - this is crudeness.”17

Climacus is pointing us towards something uncomfortable at the very heart of Christianity: we are called to absolutely relate to the absolute, the God who calls all things to an end and renews them in a new life and a new light—which is realised in the “open wound” of infinity which we are called to pull open, pull apart and suffer with. To “be the open wound to transcendence”, tearing open received wisdom with burning faith—this is the freedom of Christ’s gift for us18. Like Abraham at the foot of Mount Moriah, like Peter watching his beloved friend walk into the hands of the enemy, like Paul casting off his Pharisaic trappings and exposing the thorn in his flesh, Climacus identifies, in his unusual, detached understanding of Christianity, that to be a Christian is to be constantly prepared to be torn from life and recreated anew. And, in this stunning silence of subjectivity, where the wound is opened, faith is acquiring that which we don't have as in faith, we are born anew19.

“God creates everything out of nothing—and everything God is to use he first turns to nothing”20

God’s infinite negation of humanity, the divine “no!” to humanity’s sagacity and overconfidence, shows us the most basic truth that united both Socrates and Kierkegaard: the truth is that we know nothing about God without God’s help and that we must first that we both know and are nothing without God’s help.

“To love God is to love oneself truly; to help another person to love God is to love another person; to be helped by another person to love God is to be loved.”21

Instead of the overconfident, Vordenken culture of the fundamentalists and the puritans22—where we presume what God has guided us towards, as opposed to listening for the path to forgiveness—S. K. rebukes us and rips open our wounds of infinity; who are we to wield the sword when Christ’s necessary revelation in time was marked with gentleness, encouragement, and forgiveness?

The openness of Christianity tells us that there will always be times when the earnest believer acting in earnest faith will transgress the boundaries of die Sittlichkeit and step outside of “the ethical” into an expression of earnest faith—we will ready ourselves to slaughter our firstborn (Genesis 22:10), we will allow a friend to walk into certain death (Matthew 16:23), we will abandon a spouse and travel to the corners of the earth in order to place the absolute in the highest because it is the absolute. Here, the crossover in “the aesthetic” and “the ethical-religious” becomes clear once more—meaning changes to our subjective perspectives as we are torn from the comfort of received religion, as if Christ came to administer formal baptismal ceremonies, afternoon tea, and handshakes; the relativism of the aesthete’s “absolute-hopping” is transformed into the journey of life in the body of Christ. An understanding of God’s “yes!” to the Christians, not as amor fati but amor voluntatis Dei. In those beautiful words of Isaiah which crush any possible reading of scripture as fatalist and determinist:

I heard the voice of the Lord, saying:

“Whom shall I send,

And who will go for Us?”Then I said, “Here am I! Send me.” (Isaiah 6:8)

Isaiah’s choice—the earnest cry of the one reduced to nothing before the everything—is not a story of a strange man from a desert culture, but the model for the believer. As Christ kneeled in the Garden of Gesemathe, as Isaiah turned his eyes skywards; “here I am! You have chosen me and I have chosen you!”

Regardless of who we are at any particular moment, within any particular social order, faith is always possible and there is always a choice for us to undergo repetition to express an absolute love for God in our actions. For the one who is caught up in Bayesian probabilities and formal proofs for God’s existence, I hope it is clear that they are speaking a different language to our Melancholic Dane, to Isaiah, to Christ Himself.

So, what does this mean for the believer?

“In Either/Or… the subjective decision to comport oneself as if there were a God and real values is seen as a necessary condition for the objective discovery that there is infact a God and real values.”23

We collapse the subject-object distinction here: only by making the jump into discipleship can we understand. The complete openness to the possibility of becoming a martyr is a choice that is always present; not a will to become a martyr, but an openness to offer ourselves up to the absolute if such a thing is required. Outside of that, there is nothing that den Enkelte can do24 because not one iota can be added to God’s plan.

…in the political

And here, possibly out of order, we come to our political reflection that follows from the theological implication. When we have related ourselves to the absolute absolutely, what does that mean for our political actions in a world where the political structure is a jealous God for our absolute relation?

“It suggests rather that one relativizes what was once central as a guiding principle in favor of a higher ideal that engenders a greater degree of ethical, social, and personal harmony. Hence the dominant metaphysical and ethical schemes are retained (repeated), but in the process they are kept open to change and continual correction.”25

Political intervention in the life of the believer, either by the state or the baying “Crowd” under its sway, is an intervention that is met with theological indifference; we hold onto our Christian perspective in opposition to the demand that we try out something more modern, more sagacious, more in line with those who would have us surrender our rootedness in the journey that began at the foot of a cross in Golgotha. “Politics is not everything” here means that we are not instantly torn from our life path simply because “the one” has clapped; crisis does not descend upon us due to political intrigue or an invasion or, possibly, even the telling signs of a genocide spilling out into reality—because we are related absolutely to the absolute. Don’t mistake this for inaction or bourgeois indifference to the plight of the neighbour, my reader, no! This is a simple statement that, regardless of what happens, we shall als wäre nichts geschehen [as though nothing had happened]26 because our lives are committed to, first and foremost, the understanding of the God-relationship in relation to us and then our relation, through the God-relationship, out towards the neighbour; because, first and foremost, “the vertical relationship “God to man” and the horizontal relationship “brother to brother” are inseparable”27. Our duty to the Ukrainians, to the Russians, to the Palestinians, to the Israelis, to the Burmese, to the America, to everyone is not from “the one” calling us into the chaos of “the vortex” as part of “the Crowd”, but rather that our actions proceed from an earnest love for God in the knowledge that our relationship to God is only fulfilled as long as it is extended to the neighbour.

Our political actions are expressions of our theological groundings, which means that a new crisis in a fallen world is merely a new situation in which we express the freedom of “the ethical-religious”—it is not an excuse to abandon ourselves towards new, sagacious goals.

And how did S. K. lead the charge, sound the trumpets towards this end in his own time? By absolutely relating to the absolute in theological terms and relating relatively to the relative in political terms:

“That the state in a Christian sense is supposed to be what Hegel taught—namely, that it has moral significance, that true virtue can appear only in the state… that the goal of the state is to improve men—is obviously nonsense.”28

“Christianity is political indifference; engrossed in higher things, it teaches submission to all public authorities.”29

In this way, S. K. was aware of the temptation of “worldly shrewdness”30—the pragmatic view that principles can be sacrificed because the world, in its fallen imperfection, can never approach the perfection of the Christian message. We are not improved for being absolutely related to a new relative problem from a relative state, but nor are we discharged from our duty to both God and the neighbour due to some particular desire to rebel for worldly goals; we are free from the nihilist imposition of the state and also from the despair of having to overcome the seemingly impossible object that stands against God31, something outside of our power. It is impossible to overcome all the evil of the world, to act as the Messiah—as such, we are released into God’s hands when it comes to the encroaching diminishing of possibility by the state.

However, that impossibility does not excuse the Christian from acting Christianly; to decide that we can do away with theology when the world becomes difficult means that we are no different than the Danish establishment, the Nazi collaborators in the Lutheran church, or the current American political circus. We have dismissed Christ, elected that our own authority precedes His and that He should wait for the appropriate moment for us to allow Him back in again. If we really believe that we have taken crosses in order to follow Him, then we should be aware that we are called to the impossible—even in the arena of the “art of the possible”. By acting Christianly towards the neighbour, we are reminded that “you shall love the neighbour” implies “you can love the neighbour”32, both in times of peace and in times of war—if our inaction when the enemy is not at the gate embarrasses us when the adversary appears, that is evidence that we had forgotten our duty to the neighbour due to worldly comfort. Again and again, Kierkegaard reminds us that the tree shall be known by its fruits33.

Let’s turn down the temperature: the point here is not to fall into the erroneous, but presumably well-intentioned, faithlessness of fanaticism. If to have personal faith requires us to have a personal self, then disappearing into “the Crowd” (albeit a “Crowd” that is, superficially, more to our tastes than any other particular “Crowd”) is a step away from the divine; we invite the social manipulation to create religious terrorists under the banner of whatever religiously-disguised statecraft suffices relative goals34. Becoming a part of a “Christian” “Crowd” is no better, so it must be dismissed. If we are to remain faithful, those horrible, terrifying words will hang over us: “If you can believe, all things are possible to him who believes” (Mark 9:23).

The point to take from this absolute relation, my reader, in terms of ethical action, is that neither Christ nor S. K. viewed a crisis as the impetus for a change in action. If not one iota can be added to God’s plan, then, it follows, that we are called to accept the world in its moments of beauty and its moments of violence. Some things are out of our control, but within God’s; some things will attempt to force us to act against our better judgement, but God will provide guidance. Becoming an ethical agent, for S. K., for the Christian anarchist, is to say that “I shall love my neighbour” implies “I can love my neighbour”—at all times. And, if you can believe it, all things are possible to him who believes: as such, the notion that I can love my neighbour is expressed in a potentially infinite number of ways.

So, how can and shall we love our neighbours?

“But let me give utterance to this which in a sense is my very life, the content of my life for me, its fullness, its happiness, its peace and contentment. There are various philosophies of life which deal with the question of human dignity and human equality; Christianly, every man (the individual), absolutely every man, once again, absolutely every man is equally near to God. And how is he equally near? Loved by Him. So there is equality, infinite equality between man and man.”35

“Kierkegaard and the Critique of Political Theology”, A. Rudd, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, p. 25, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

“The Obstacle” in Training in Christianity and the Edifying Discourse which 'Accompanied' It, p. 26, Anti-Climacus, edited by S. Kierkegaard

“Enough is Enough! Fear and Trembling is Not about Ethics”, p. 194, R. M. Green, from The Journal of Religious Ethics, Fall, 1993, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Fall, 1993)

Politics of Exodus: Søren Kierkegaard's Ethics of Responsibility, p. 45, M. Dooley

Ibid., p. 94

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 109, J. Climacus, tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

Kierkegaard's Indirect Politics: Interludes with Lukács, Schmitt, Benjamin and Adorno, p. 18, B. Ryan

Pap. X 5 A 146, 1853

“A New Way of Philosophizing”, from On Kierkegaard and the Truth, p. 54, P. L. Holmer, edited by D. J. Gouwens and L. C. Barrett III

Politics of Exodus: Søren Kierkegaard's Ethics of Responsibility, p. 118, M. Dooley

Kierkegaard's Indirect Politics: Interludes with Lukács, Schmitt, Benjamin and Adorno, p. 1, B. Ryan

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 70, J. Climacus, tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 81, S. Kierkegaard

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 78, J. Climacus, tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

"The Gospel of Sufferings: Christian Discourses", from Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, S. Kierkegaard, p. 294

The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air, p. 25, S. Kierkegaard

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 62, S. Kierkegaard

“Destitution of Sovereignty: The Political Theology of Søren Kierkegaard”, S. Brata Das, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

The Dialectical Self: Kierkegaard, Marx, and the Modern Subject, p. 64 J. Aroosi

Pap. XI I A 491

Works of Love, p. 107, S. Kierkegaard

Beyond Immanence: The Theological Vision of Kierkegaard and Barth, Kindle location 2955, A. J. Torrance & A. B. Torrance

“Kierkegaard's Metatheology”, T. P. Jackson, from Faith and Philosophy, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 75

Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship, p. 277, V. Eller

Politics of Exodus: Søren Kierkegaard's Ethics of Responsibility, p. 128, M. Dooley

Theological Existence To-day!, p. 9, K. Barth

The Theology of Anabaptism, p. 121, R. Friedman

JP IV 4238

JP IV 4193, in reference to Romans 13:1

“When is “the Instant”?” from The Instant, no. 10, from Attack upon “Christendom”, p. 281, S. Kierkegaard

Sickness Unto Death, p. 12 Anti-Climacus, ed. S. Kierkegaard

Works of Love, p. 265, S. Kierkegaard; Love's Grateful Striving: A Commentary on Kierkegaard's Works of Love, p. 60, M. J. Ferreira

“Foreword”, G. Marino, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

“The Crowd and Populism: The Insights and Limits of Kierkegaard on the Profaity of Politics”, p. 19, J. J. Davenport, from Truth is Subjectivity: Kierkegaard and Political Theology, ed. S. W. Perkins

For Self-Examination, p. 5, S. Kierkegaard

BEEN WAITING PATIENTLY FOR THIS ONE!!!!!!!