Christian pessimism and "The Unhappiest Ones"

A Kierkegaardian deliberation on depression, despair, and faith

Philosophical pessimism is already a strange thing - championed in drudging poetics by the likes of Arthur Schopenhauer, Philipp Mainländer, and Emil Cioran, it lacks any real core doctrine that would unite it as a real school of thought. Themes overlap, most notably that life is not worth living; there is a distinct lack of meaning in the universe, bordering or sometimes jumping two-footedly into nihilism; and generally creeping into the darkest aspects of human doubt, such as antinatalism and National Socialism.

Its antipathy leads us to think that maybe they are right - there really might be nothing for us in this life, that it might be immoral to bring children into this world, that maybe humanity is isolated and an aberration of nature - "[i]n the beast, suffering is self-confined; in man, it knocks holes into a fear of the world and a despair of life."1 Although the infamous work of David Benatar has found pockets of academic response (especially in regards to the questionable “asymmetry argument” from Better to Have Never Been), philosophical pessimism finds itself on the fringes on modern discussion; haunting ethicists like a cruel joke, the constant reminder that even the most well-established and well-regarded moral arguments will crumble to dust if we hold that these sagacious reflections are only “the art of masking inner torments”2.

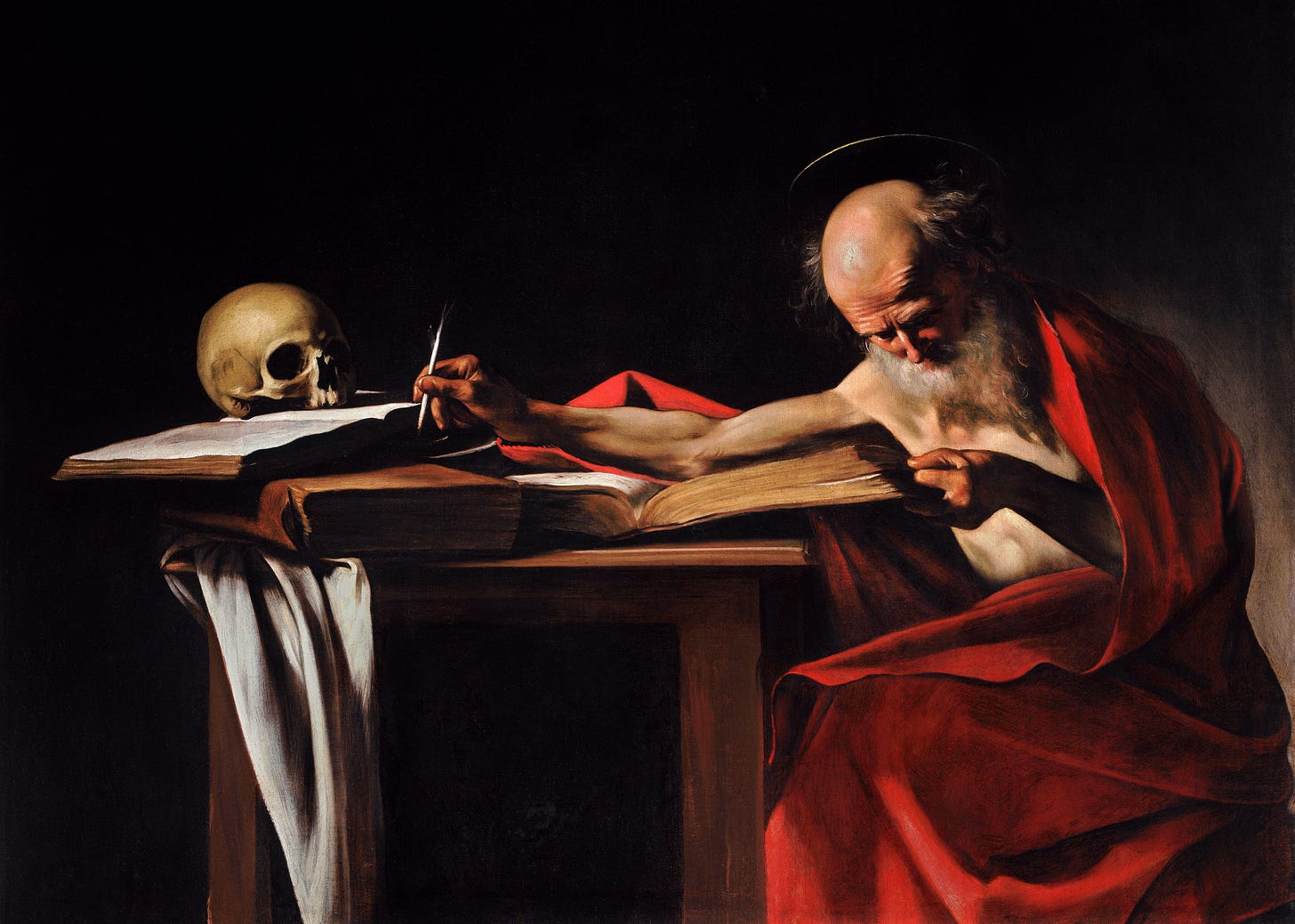

Of course, this then stands in an even stranger relation to the topic of the Christian faith: what precisely does the problem of evil manifest as a world-view have to do with the promise of Christ? How could anyone who has heard the good news still hold that life isn’t worth living; that suffering is the human condition? One such person was Søren Kierkegaard, the depressed Christian par excellence, who serves as our worrying figurehead, steadfast reprover, and Knight of Faith against the temptation of pessimistic depression.3 By analyzing Anti-Climacus’ complex phenomenology of despair in The Sickness Unto Death, the extended treatment of Angst in Vigilius Haufniensis’ The Concept of Anxiety, and the personal writings of Kierkegaard, we can create a picture of the Christian pessimist. But, for the sake of this short exploration, we will look at two looming figures of despair that appear in S. K.’s oeuvre.

The self-righteous moralism of theologians

Although it would be strange to suggest that Christianity doesn’t involve some kind of ethical thought (although it is decidedly less strange to wonder exactly about what kind of ethical thought that would be…4), S. K.’s particular approach to a Christian anthropology and his phenomenology of despair raised a great deal of fury from a variety of theological voices. As noted in Holmer’s On Kierkegaard and Truth, a number of significant voices turned very sourly against S. K.’s particularly morose approach to Christian thought:

Ernst Cassirer insisted that Kierkegaard was an unbeliever and that the early non-religious writings revealed the true man. The later Christian writings, he believed, were in consequence of a failure of nerve and a sense of filial duty. Walter Rehm argues that Kierkegaard was a seducer and, further, that he was not a believer, but was self-seduced. Another author, Giovanni Papini, once said: “Kierkegaard was a terrible man. He attacked Christianity and all Christian and civil virtues.” Papini is quoted to this effect by Walter Lowrie, who reported a conversation with him in a letter to Professor David F. Swenson.5

Love thy neighbour, indeed. Here we see some particularly barbed critiques of Kierkegaard’s character (all the more common than critiques of his work), specifically his apparent lack of faith, his apparent seductive temptation of others, and the outright assessment of him as a “terrible man”. I’m afraid my readers will have to wait for an update on which of these thinkers had the glory of casting the first stone, but it is slightly disappointing that Holmer saw it fit to leave out Kaufmann’s accusation of Kierkegaard’s unbridled authoritarianism6 - we would have had a full house.

Needless to say, any kind of defense of Christian pessimism will presumably draw similar ire. Having found similarly sweeping statements from contemporary theologians (such as ones who offer new translations of the Bible along with their apologism for universalism…), it would be reasonable to suggest that S. K.’s aims in outlining his dour understanding of Christianity are still misunderstood - if we didn’t know better, we might even say intentionally or, even worse, from a position of ignorance. Instead, I will try to outline some of the distinct pessimistic characters of S. K.’s work, situate his own depressive episodes, and show how this relates to his understanding of the human condition as “the absurd”.

The Unhappiest Ones

S. K.’s oeuvre has more than a few pessimistic characters. Starting from his own reflections on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where S. K. (in all his eccentricity) found himself in the despairing figure of the Danish Prince7, it seems that the young Søren had always struggled with a deeply melancholic view of the world that he couldn’t shake. Although it would be too much to point to this as the cause of his extensive literary output, it obviously played a part - although Christian in its overall aim, the aesthetic indulgences of S. K.’s body of work explored a variety of characters who teetered on the edge of absolute despair, “the demonic” anxiety about the good8 that pushes us away from God, love, and trust. In some ways, the overall autobiographical tone of the earlier works9 leads us to suggest that this fear of the demonic is a part of the way in which S. K. guarded himself against indulgent depressive “motionlessness”. In an almost cruel trick, however, this approach had a deeply pietist purpose: only through a genuine appropriation of pessimism is one capable of “coming out the other side alive”10 as a Christian.

But, to fully unpack this, we need to explore two characters: The Unhappiest One and the Unhappy Poet.

At a graveside with The Unhappiest One

Appearing in “A”’s writings in Either/Or11, “The Unhappiest One” is a character who is only referenced - we never see him, we never hear from him, we can only assume his existence from his empty grave. But the poetic melancholy rings through the text, stripping back the otherwise comedic and carefree pulse of “A”’ into a morose, lumbering self-reflection. Some of these are especially contrary to pervasive Christian thought, most notably:

"Happy is the one who died in old age; happier is the one who died in youth; happiest is the one who died at birth; happiest of all the one who was never born."12

For those of us who like to keep up with the more obscure side of philosophical thought, this echoes of David Benatar’s argument(s) for anti-natalism: that “coming into existence is always a serious harm”13. This morose starting point really sets the tone for the aesthete - life simply becomes more and more depressing as we age, as the curtains are drawn back; we are forced to settle for a lesser state by virtue of existing, with the greatest of all conditions is simply to have been forced to deal with the “sickness unto death”. Although many would disagree that Benatar’s argument hits the mark (hence the refusal to accept that procreation is prima facie immoral), there is a tempting poetic ennui here: wouldn’t it be simpler for us if we never have to deal with this pain and suffering? Would an all-loving God really subject us to these trials, even when the greatest of them might be nothing more than getting out of bed? The tone is set, the gauntlet must be run: how does the Christian overcome this problem?

For a religious tradition that has placed emphasis on the gift of life, the importance of children, and the joy of God’s creation, this hard turn towards anti-natalism is a shocking one. “A”, of course, was not a Christian - nor did he pretend to be a Christian. But this is exactly the kind of statement that is presented as evidence in the court of academic opinion, which surprisingly has taken a dim view of the sworn anti-academic armed with the Protestant Principle and the heavy burden of his own despair14. Before we can possibly explore what Kierkegaard meant in saying that faith could do more than move mountains, it can move despair, we should explore “A” in his indulgent praise of “the Unhappiest One”.

The most important aspect of “the Unhappiest One”’s unhappiness is that he can’t die.

As is well known, there is said to be a grave somewhere in England that is distinguished not by a magnificent monument or a mournful setting but by a short inscription-"The Unhappiest One." It is said that the grave was opened, but no trace of a corpse was found. Which is the more amazing - that no corpse was found or that the grave was opened? It is indeed strange that someone took the time to see whether anyone was in it. When one reads a name in an epitaph, one is easily tempted to wonder how he passed his life on earth; one might wish to climb down into the grave for a conversation with him. But this inscription-it is so freighted with meaning!15

But why does this lead to unhappiness? Because, quite simply, the individual cannot find rest from despair, he can’t find his solution for a longing for rest in the grave; doomed to existence, doomed to remain alive, the solution evades “the Unhappiest One”16. This comes, however, from the very distinct problem that pervades human existence: the nostalgia and longing for “the present”. Echoing Augustine, there is an important emphasis on this elusive notion of the present - that is where “the Moment” exists, where God acts in us17.

“The Unhappiest One”’s broken understanding of time plays an important part in S. K.’s philosophy, especially in his early works. “The Unhappiest One” is constantly chasing the solution to his unrest because he can’t recognize that he is lost; when he is lost in the "present" of the past or the "present" of the future, everything seems lost and there is no possible solution to his crisis - he will do anything but be in the present itself18. This continuous engagement with “time”, or, rather, “time running out”19 (something that evades “the Unhappiest One”) in S. K.’s work is a stark reminder of the importance of situating the self within the self - at least in part. The aesthete tries to escape their “finitude”, attempting to become God-like in their absolute freedom. No, says Kierkegaard; you are held in place and must wrestle with the fact, possibly even wrestle with God Himself, that you are not entirely free. Regardless of what “the Unhappiest One” wants, he is stuck in the present as a fact and his attempts to go beyond that fact lead only to his despair - ultimately, his undying despair about the nonexistence of his rest.

By trying to place the self outside the self, i.e., either in the nostalgic memories of times gone by or in the “imagination” of “hoping for eternal life”, there is a constant unrest, a constant despair, a constant failure to understand that a particular individual can only take particular actions20. Simply put: universality and particularity are not on the same plane21; how can we expect our simple finitude to achieve the infinite task of the promise of heaven on Earth? Here, we find ourselves in a strange position of pseudo-Pelagianism: not only is it our task to wrest salvation from God, but we will also wrest it from the Almighty to be realized right now! In this sense, specifically Christian attempts at creating heaven on Earth via our own power, which is especially prominent in the various liberal theologies of the late 60s to 70s (liberation theology, feminist theology, “Death of God” theology, etc.), are predicated on understanding the infinite task that lies before us and imposing that stress onto the finite self.

“The Unhappiest One” is unhappy as he can find no rest in the grave; the contextualist Christian may be no different here if they find no rest from the world.

The psychological assessment of the Unhappy Poet

There is something important to emphasize in “the Unhappiest One” - he is an aesthete, torn from desire to desire. In attempting to find a contingent solution to his problem, he finds himself essentially dealing with the absolute relativity of human desire. Eventually, we run out of passion towards our various sufferings - we no longer find paragliding particularly thrilling anymore and it becomes a chore; the beauty of the other fades into a comfortable security of the known; the responsibility towards those we bring into this world becomes a lot less miraculous when cleaning up vomit at 4 in the morning. In short: a life where we do not undergo “repetition” of our deeper wants when desire fades is a life without existence22.

But “the Unhappy Poet” isn’t in that situation. He has deliberated23 about what he must do, heard the promise, but still finds that he cannot believe - he is stuck in the collapse before the “leap”. The autobiographical insert isn’t particularly long, so it can be easy to miss it in the Moment:

Such a poet may have a very deep religious need, and the conception of God is included in his despair. He loves God above everything, God is for him the only comfort in his secret torment, and yet he loves the torment, he will not let it go. He would so gladly be himself before God, but not with respect to this fixed point where the self suffers, there despairingly he will not be himself; he hopes that eternity will remove it, and here in the temporal, however much he suffers under it, he cannot will to accept it, cannot humble himself under it in faith. And yet he continues to hold to God, and this is his only happiness, for him it would be the greatest horror to have to do without God, "it would be enough to drive one to despair"; and yet he permits himself commonly, but perhaps unconsciously, to poetize God, making him a little bit other than He is, a little bit more like a loving father who all too much indulges the child's "only wish." He who became unhappy in love, and therefore became a poet, blissfully extolls the happiness of love-so he became a poet of religiousness, he understands obscurely that it is required of him to let this torment go, that is, to humble himself under it in faith and to accept it as belonging to the self - for he would hold it aloof from him, and thereby precisely he holds it fast, although doubtless he thinks (and this, like every other word of despair, is correct in the opposite sense and therefore must be understood inversely) that this must mean separating himself from it as far as possible, letting it go as far as it is possible for a man to do so. But to accept it in faith, that he cannot do, or rather in the last resort he will not, or here is where the self ends in obscurity.24

Illustrated by walking the line between faith and despair, “the unhappy poet” is the pessimist qua disappointed optimist. In carrying out the deliberation to understand that the promise delivered to him from God is from the Almighty, the All-Knowing, the All-Loving, and that the promise is simply a matter of saying “yes!” in response to Christ’s own affirmative action, we find the “patient” to Anti-Climacus’ psychological approach is simply incapable of teetering over the edge into faith proper. The notion of the weight of “the temporal” acting as an imaginary eternal weight is the heart of this issue: when the despair of our life weighs on us so heavily, how can we possibly believe that God could remove it in the afterlife? God has created a stone so heavy that He cannot lift it - and it hangs around my neck.

Thinking back to the frantic prose of The Concept of Anxiety, Kierkegaard presents himself in the raw image of his failure to find the faith he desperately desires: “the demonic reaction against the good”. The poet of religiousness is simply caught in the same trap that he was trying to avoid - the trap closes on him and he longs for a “leap” which will deliver him to rest. Until that moment, there is only suffering under the weight of his sinful depression, the potentially self-righteous indulgence25 in the suffering of the failure to trust is a mysterious point of no return for the Christian: either “leap” into the ethical-religious and accept God openly, holding that through the Lord all things are possible, even lifting the immovable rock or accept that God cannot take a burden so heavy from me, even in the afterlife, even in death. Here, we find that depression and pessimism seem to go hand-in-hand.

But Anti-Climacus calls us beyond this - Kierkegaard qua “the Unhappy Poet” is called beyond his suffering and encouraged to go as far as possible in order to separate himself from his obsession with temporality. In this moment, he has the opportunity to “leap”. But this requires something of “the Unhappy Poet”:

"Christian heroism, and indeed one perhaps sees little enough of that, is to risk unreservedly being oneself, an individual human being, this specific individual human being alone before God, alone in this enormous exertion and this enormous accountability."26

This place “out on the 70,000 fathoms deep”27 is the place where Christian pessimism escapes the accusations of “disappointed optimism” - it is the assertion of a commitment to the fact that this world has nothing for the Christian - without holding God as the most important first. When we deliberate between the necessary and the contingent, we find that contingency is only a fleeting moment of time, suffering in time - even for an extended period of time - is nothing in comparison to the everlasting present of eternity. Much like “the Unhappiest One” searches for a way to escape his present through the “present past” and the “present future”, our “Unhappy Poet” clearly shows us that he recognizes the present; he understands the bird of the air and the lily of the field are his teachers28 and that he must vault past the despair of worldliness over the obedience of the bird and the lily into the commitment of the Christian: "[b]y dying the bird ceases to live, but the Christian lives by dying."29 In an obvious allusion to the call that “if any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me” (Matthew 16:24) and to recognize that “the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Galatians 6:14), S. K. laid the challenge at his own feet via the pen of Anti-Climacus: the genuine pessimist will recognize that, like the bird, the lily, the cross-bearer, and the apostle, the choice to disavow this world is a choice that we can make: we can renounce it and find rest in the body of Christ.

“The Unhappy Poet” is unhappy because he hears the promise, knows the truth, and still cannot believe; will this weight be lifted? Can we truly only suffer once?30

The Freedom in the Thought that Against God, We Are Always Wrong

This exploration of pessimism isn’t a para-academic curio dragged out over a few thousand words. Instead, it sets the basis of Christian anarchist thought: the deep pessimism and distrust for the capabilities of “arkydom” to provide any kind of real Christian solution, a Christian society to the world. In this sense, the Christian anarchist both holds to the Pauline passionate dying to the world (Galatians 5:24) and also avoids the Schopenhauerian “disappointed optimism” that is really a cover for a tantrum about one’s lack of recognition that S. K. diagnosed in his later years31. In the effort to truly cast off all accusations of Pelagian political theology, here we find Kierkegaard at his most committed to what would be called the Protestant Principle: nevertheless not my will, but thine be done (Luke 22:42); nevertheless not our political wants, but the God’s plan for us in this world.

Despite the obvious temptation to view this kind of approach as necessarily quietist (surrendering political will to an almost esoteric, almost Schleiermacherian(!) appeal to revelation and divine guidance), I am actually saying the very opposite as a statement of faith. If the Spirit does truly work in us, if God does reach out into his creation to offer us guidance, we should maximize that. And our mode for understanding that guidance is through scripture, through the church, and through the duty we have to one another. By rejecting the temptation to become either “the Unhappiest One” or “the Unhappy Poet”, we see what faith isn’t - and only by identifying what faith isn’t, says S. K., can we truly explode out into the rest in the body of Christ. Only by overcoming the absurd can we overcome the negative understanding of faith32 through the “leap”.

Lord, forgive me, a sinner. Have mercy on me for my lack of faith - increase my faith so that I can see that this life is not the end; that the quiet hope that the dead will wake up is more than a dream, more than a worry, more than despair made thought. Lord, forgive me for my lack of faith that my life can be worth living. Lend me the strength to recognize the duty that lies, but is not laid upon me; give me refuge in the body of Christ, so that I can find the freedom to do your will. If there is one thing and one thing alone that I will do: I shall be recognized as a Christian in the hereafter.

Amen.

"The Last Messiah", p. 2, P. Zapffe

"On Death", from On the Heights of Despair, p. 27, E. Cioran

By no means should this be understood to imply that by faith and faith alone can we expect to overcome the challenges of depression, nihilism, and similar issues - while some have found success in these methods (possibly including Kierkegaard himself), it would be unwise to turn away from modern techniques for dealing with mental health issues in a strange act of self-justification: And the Lord God said, “It is not good that man should be alone. (Genesis 2:18)

"On Keeping Theological Ethics Theological", from The Hauerwas Reader, p. 53, S. Hauerwas, ed. J. Berkman and M. Cartwright

"A Glance at a Contemporary Effort in Danish Philosophy", from On Kierkegaard and the Truth, p. 36n, P. L. Holmer, ed. D. J. Gouwens and L. C. Barrett III

“Kierkegaard”, W. Kaufmann, from The Kenyon Review, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Spring, 1956)

"Kierkegaard and Shakespeare", J. E. Ruoff, from Comparative Literature, Autumn, 1968, Vol. 20, No. 4, p. 344

The Concept of Anxiety, p. 118, V. Haufniensis

Especially Either/Or and Repetition

"...the humorist himself has come alive to the incommensurable which the philosopher can never figure out and therefore must despise". JP 2:259 - my equation of “the humorist” and the Christian here is intentionally Kierkegaardian.

Specifically in the lectures to the συμπαρανεκρώμενοι, “The Unhappiest One”, p. 210-224, Either/Or, vol. I

"The Unhappiest One" from Either/Or: A Fragment of Life, p. 221, ed. V. Eremita

“Still Better Never to Have Been: A Reply to (More of) My Critics”, D. Benatar, from The Journal of Ethics, Vol. 17, No. 1/2, Special Issue: The Benefits and Harms of Existence and Non-Existence

"The Gospel of Sufferings: Christian Discourses", from Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, p. 235, S. Kierkegaard

"The Unhappiest One" from Either/Or: A Fragment of Life, p. 210, ed. V. Eremita

"To Die and Yet Not Die: Kierkegaard's Theophany of Death", S. D. Podmore, from Kierkegaard and Death, p. 48, ed. P. Stokes and A. J. Buben

"The Crowd is Untruth", S. Kierkegaard

"The Unhappiest One" from Either/Or: A Fragment of Life, p. 223, ed. V. Eremita

Especially in "At a Graveside", from Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions, S. Kierkegaard

"Derrida, Judge Wilhelm, and Death", I. Duckles, from Kierkegaard and Death, p. 225, ed. P. Stokes and A. J. Buben

"Equality: a Proposal Rooted in Kierkegaard's Theological Anthropology and Theology of Love", N. Marandiuc, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, p. 98, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

For two excellent commentators on S. K. in relation to Frankfurt and the need for the free choice to repeat our will, see "Frankfurt and Kierkegaard on BS, Wantonness, and Aestheticism: A Phenomenology of Inauthenticity", J. Davenport, from Love, Reason, and Will: Kierkegaard After Frankfurt, ed. A. Rudd and J. Davenport and Taking Responsibility for Ourselves: A Kierkegaardian Account of the Freedom-Relevant Conditions Necessary for the Cultivation of Character, P. Carron

In the Kierkegaardian sense of identifying the necessary and holding it in dialectical tension with the contingent self - see "The Gospel of Sufferings: Christian Discourses", from Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, p. 310, S. Kierkegaard

Fear and Trembling and The Sickness Unto Death, p. 376-377, Anti-Climacus, ed. W. Lowrie

Epistle to the Romans II, p. 276, K. Barth

Sickness Unto Death, p. 5, Anti-Climacus, ed. H. V. Hong and E. H. Hong

Works of Love, p. 363, S. Kierkegaard

The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air, p. 36 S. Kierkegaard

"The Cares of the Pagans" in Christian Discourses, p. 17, S. Kierkegaard

"States of Mind in the Strife of Suffering" in Christian Discourses, p. 97, S. Kierkegaard

"Kierkegaard's Pessimism", p. 37, P. Jepsen, from Danish Yearbook of Philosophy 56 (2023)

JP I, 9

Nihilism is so rampant in young people these days. If only we all had some Kierkegaard to inoculate us against this virus..

Wonderful work! Your posts always give me a bit of an intellectual shock. I'm not sure how else to describe it. I can't even begin to describe how much I look forward to these popping up in my RSS feed!

PS: Around 25 did you mean possible instead of impossible?