Christian anarchism and the Problem of Nihilism - part IV

Creating contours via negativa

To read the other pieces in this series, see below:

Laying out a view of Christian anarchism that is broadly Kierkegaardian in flavour often comes with the exact same problems that all political thought has: either it is far too abstract and leads us into an apparently acosmic individualist stance where the existence of the other, the fellow believer, is, at best, a happy convenience where the other person acts as an object for us to exercise the divinely-mandated love for the neighbour before receding back into the lavish and self-indulgent holier-than-holy introspection of “hidden inwardness”, or disappointingly obvious statements which rise to the same level of insight as a lukewarm “what would [insert secular group here] do?” that fails to be Christian, faithful, and - worst of all - interesting. The radicalism of the theory sloughs away to leave a rather bare, ineffectual skeleton that, without the pomp to hide behind, could have been written on the back of a napkin. Tolstoyan anarchism, for example, could almost be reduced to “be nice and ignore Paul”1 - hardly radical and even less Christian.

In an effort to avoid that, we shall make Christian anarchism (as well as the negation of Christian anarchism) concrete. Through the thought of S. K. and Vernard Eller, we can show that Christianity is anarchical - and its radicalism, in the strangest sense, is in the quiet voice in the desert roaring through the quiet life of the faithful. Firstly, we assess the actions of two Christians who fell into arky faith; after that, we carry out a deliberation between our two wandering thinkers; and finally, we relate this account back to S. K.’s vision of folkekirken2 and how this overcomes the nihilism of modernity.

Sola fide or sola gladio?

For S. K. and so many Christians in the modern world, the Reformation is viewed as one of the great occasions that, even if largely romanticized in the popular understanding of the events, led to the church becoming unyoked from its medieval baggage that had led to a system which so unsatisfactory in the eyes of the faithful. Not only did it unleash a wave of theological and philosophical revolution in Europe that led to the very foundation of a distinctly new European view of life, it also set off radical changes in the Catholic Church and allowed for the emergence of the Anabaptists, sometimes erroneously considered another flavour of Protestantism. As Eller argued at length, the Anabaptists may be the most extreme form of theological revolution that the world has ever seen3 (although, it would be unwise to consider them like Protestantism taken “all the way”4, as is sometimes presented by Protestant dismissers5 and largely secular “Christian” anarchists6) and, as one might have expected by this point, this plays well for the broad themes of S. K.’s work - although his Lutheran understanding of the sacraments and various other matters of dogma make the comparison a little untidier than Eller might have wanted.

As Eller would carry on in his later work Christian Anarchy, however, the seemingly radical edge of the Reformation was dulled. There are two figures of note here, one you will most likely have heard of and another who you might not - and if you have, it may have been an altogether negative account.

Martin Luther - the failed anarchist

Calling Martin Luther an anarchist is a very odd thing to do. Of course, we’re not doing that, we’re doing something even stranger - calling him a failed anarchist. This is because the pulsing vein of Christian anarchism is found in Luther’s thought and was essential for his (initially unintended) opposition to the Catholic church to the point of the radical separation which still lies in the foundations of Western Europe today. In short, this passion for God against the indifference to the world can be captured in sola fide, sola scriptura, and the priesthood of all believers.

Why was Luther not a Christian anarchist, despite his commentary to the effect of the perfect Christian society of virtue? His praxis was political, i.e. arky faith7. He preached the priesthood of all believers whilst securing the arky-power distinction between clergy and laity. Although his faith professed the unstoppable force of faith alone against the scourge of the world, he became a politician and more concerned with victory than “how” he should be victorious. As evidenced in the reaction of those “radical” Reformers such as the Anabaptists and in Luther’s own fatuous Table Talks, the ethical-religious element of Protestantism initially “ripping through” the stagnancy of the post-medieval church whimpered into background of false essence, an ecclesiastical mauvaise foi8, that sinks into the comfort of mass conformity via the collapsed ethical or, even worse, the trickery and deception of the aesthetic that hangs high above reality. On two fronts, Luther failed the radicalism of his thought:

Arbitrariness

Firstly, by accepting that the turgid Catholicism which he viewed as fallen could be excused if it was pragmatic to excuse it. This seems like an arbitrary and strange view: by what criteria are certain elements of rebellion pragmatic and others unpragmatic? Menno Simons, an early Anabaptist and sometimes admirer of Luther, was altogether unimpressed with this weakness of will. As Horsch noted, reflecting on Simons’ polemics against the apparent continued Catholicism of the apparent Protestants:

“Luther and Zwingli were of the opinion, as has been pointed out, that from motives of consideration for “the weak” who must not be offended, unscriptural religious forms may be observed for a time.”9

“Luther as well as Zwingli did not forsake the Roman Catholic Church, but reformed it. They were willing to retain the unevangelical forms until the state ordered their abolishment. In the matter of the reformation of the church they took only such steps as would meet the approval of the state. Thus they enjoyed the protection of the state and were never subjected to persecution. Menno Simons on the other hand united with a people who had been summarily condemned to death in the Netherlands as well as in the German Empire.”10

In this arbitrary consideration for “the weak” (whoever they might have been - and Luther was certainly caught between who it was that shouldn’t be offended), we find that Christianity is forced to take a back seat to the social reality of contemporaneity. Abraham does not will to slaughter Isaac, but collapses in despair at the thought that he might. A lack of conviction underpins this worldview: if we are justified sola fide, how precisely can we place our trust in the wrong (from Luther’s perspective) faith until a time when more favourable social circumstances emerge? This seems like cruel mockery in the face of the apostles, whose blood was spilled for the idea that the truth must not be sacrificed at the altar of untruth nor should the Christian deny God at the point of a sword. Like a prophet breathing fire against the unfaith of Luther’s “muddleheaded” cowardice, S. K. roars forward:

“The very moment untruth has killed him, it becomes fearful for itself, about what is has done, powerless through its victory, and precisely this is the untruth's defeat.”11

To hide in pragmatism, often under the guise of a willingly worldly and servile interpretation of Romans 13, what would that mean for the Christian faith? Sabre-rattling aside: can we really say that the faith should gain consent from the state in order to exist?12 Or wouldn’t the faithful know (know) that God would not abandon the faithful, regardless of the perceived power of the world?

Worldliness

As alluded to above, Luther and the other reformers held that the Catholic perspective on the faith could be left uninterrupted as long as it passed this rather loose formula: “everything that is not prohibited in the New Testament scriptures, although it is forbidden in the Old Testament, may be retained [from Catholicism]”.13 Under the threat of iconoclasm in Carlstadt, Luther concedes his revelation again - it is not an immovable fact of the divine intervening on behalf of the holy elect, but a point that can be whittled down to a pragmatic thesis, a theory amongst theories, that we can put before a council and emerge victorious when God gains the democratic consent of the clerics. Because, apparently, the Almighty now needs the approval of a counsel in order to issue commands.

To some extent, a harsh view of Luther here would be unjust. He was, after all, just one man. S. K. did not hold him personally responsible, but exploited by secular interests to their benefit - although his political stance, for example in the Table Talks and his prioritization of princely consent, made this easy to do.14 But, in doing this, he had weakened his apparently radical position: the priesthood of all believers was second to the power of the state, thereby robbing Lutheranism of its faithful edge that would distinguish it from the world15. In his revulsion to the faithful bursting forward against their oppressors16, Luther ran back to the world.

If there is a way out, S. K. considered an inverse of the Reformation necessary to overcome the errors now rife in society. This “corrective” would play on one of S. K.’s favourite Lutheran sentiments - “as Luther says, the world continues to be like the drunken peasant who, helped up on one side of the horse, falls off the other side”17:

“The future will correspond inversely to the Reformation: then everything appeared to be a religious movement and became politics; now everything appears to be politics and will become a religious movement.”18

Of course, that is not to say that S. K. was without his overall respect for Luther - in fact, it would be safe to say that he saw a great, if somewhat incomplete, image of Christian existence in Luther’s life. This becomes especially obvious within the journal musings:

“Just as Luther stepped forward with only the Bible at the Diet of worms, so I would like to step forward with only the New Testament, take the simplest Christian maxim, and ask each individual: Have you fulfilled this even approximately—if not, do you then want to reform the Church?”19

But still, he was not in a state of armed neutrality. He was not “that holy anarchist” that we are searching for.

Thomas Müntzer - the first secular anarchist

Müntzer is an infamous figure for a variety of reasons. Engels viewed him as such:

Müntzer’s political doctrine followed his revolutionary religious conceptions very closely, and as his theology reached far beyond the current conceptions of his time, so his political doctrine went beyond existing social and political conditions. As Müntzer’s philosophy of religion touched upon atheism, so his political programme touched upon communism, and there is more than one communist sect of modern times which, on the eve of the February Revolution, did not possess a theoretical equipment as rich as that of Müntzer of the Sixteenth Century. His programme, less a compilation of the demands of the then existing plebeians than a genius’s anticipation of the conditions for the emancipation of the proletarian element that had just begun to develop among the plebeians, demanded the immediate establishment of the kingdom of God, of the prophesied millennium on earth. This was to be accomplished by the return of the church to its origins and the abolition of all institutions that were in conflict with what Müntzer conceived as original Christianity, which, in fact, was the idea of a very modern church. By the kingdom of God, Muentzer understood nothing else than a state of society without class differences, without private property, and without superimposed state powers opposed to the members of society. All existing authorities, as far as they did not submit and join the revolution, he taught, must be overthrown, all work and all property must be shared in common, and complete equality must be introduced. In his conception, a union of the people was to be organised to realise this programme, not only throughout Germany, but throughout entire Christendom. Princes and nobles were to be invited to join, and should they refuse, the union was to overthrow or kill them, with arms in hand, at the first opportunity.20

But this leads us to our important question: what was Müntzer's arky faith? Eller, taking a harsh and unforgiving stance with the radical German, said we should view him as the direct arky faith polar opposite to Luther - the revolution against the establishment for the poor and oppressed is God's sword21. There is something very attractive about this worldview, it must be acknowledged; not only do the Christians have the righteousness of God on their side, but they also wield His might directly to overcome evil as well. As a Romantic image, it does something to stir the innards. We might even feel that rush of blood, imagining a Teutonic Knight in all his regalia and emblazoned with the cross to vanquish evil from God’s good earth. We might again even be tempted to refer to Luke 22:36-38 in order to justify that position and the admiration for Müntzer we still find in minor, marginalized sections of the discourse.

However, it is not that simple when we consider what it means to have “arky faith” and whether Müntzer is a “better” or even passable figure for us to direct our hopes towards. Eller elaborates:

“Müntzer's is an arky faith the polar opposite of Luther's. He is the sixteenth-century representative of today's "theology of liberation." For him, revolution against establishment arky in behalf of the poor and oppressed is God's Sword manifesting itself in history. It is true that the Peasants War supported by Müntzer came to the same sorry end as the pre-Jesus Maccabean Revolt and the post-Jesus Zealot Revolt. Yet it is indubitable that all three of these were totally "just" revolutions, turning to violence only because there was no other alternative. Müntzer was every bit as sincere and religious as Luther - and had just as credible an argument for his position.”22

However, this doesn’t fully reflect the worldliness of Müntzer to the full extent. The willingness to prioritise violence as a tactic of overcoming sits uncomfortably with Christ’s life—when can we say that violence is faithful? Could we say that at all, or does it immediately render Christian sociality as worldliness with more singing? As Ellul stated elsewhere in his “fifth law of violence”:

“…the man who uses violence always tries to justify both it and himself. Violence is so unappealing that every user of it has produced lengthy apologies to demonstrate to the people that it is just and morally warranted. Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Nasser, the guerrillas, the French "paras" of the Algerian war—all tried to vindicate themselves. The plain fact is that violence is never “pure.” Alw^ays violence and hatred go together. I spoke above of the rather useless piece of advice once given Christians: that they should make war without hatred. Today it is utterly clear that violence is an expression of hatred, has its source in hatred and signifies hatred. And only a completely heartless person would be capable of simply affirming hatred, without trying to exonerate himself. Those who exalt violence—a Stokely Carmichael or a Rap Brown, for instance—connect it directly with hatred. Thus Rap Brown declared: "Hate has a role to play. I am full of hatred, and so are the other blacks. Hate, like violence, is necessary for our revolution." Carmichael has repeatedly spoken of the close relation between hate and violence. In one of his speeches* he declared: “As Che Guevara said, we must develop hatred in order to transform man into a machine for killing.””23

By choosing to take up the sword, Müntzer has relegated the second of the Greatest Commandments to the same importance it held for Mao, Hitler, or Nasser. While S. K.’s own view of violence and the use of violence allowed a degree of greater leniency (taking it as “the rod” wielded against nations that have gone to war24), the two cases presented by Eller and Ellul can be used to dismiss the violent sword-wielding of Müntzer and his cabal during the Reformation period. While we are on the topic, the idea that Luke 22:36-38 could justify the use of “righteous violence” fails under even the slightest of theological challenges:

“The further comment of Jesus explains in part the surprising statement, for he says: 'It is necessary that the prophecy be fulfilled according to which I would be put in the ranks of criminals' (Luke 22:36-37). The idea of fighting with just two swords is ridiculous. The swords are enough, however, to justify the accusation that Jesus is the head of a band of brigands. We have to note here that Jesus is consciously fulfilling prophecy. If he were not, the saying would make no sense.”25

Regardless of how lenient we view the Christian attitude to violence, the particular failing of Müntzer’s is his zealous urge to found an army to fight on behalf of the Lord (because “God and me make a majority”26) is the instant collapse of the apparently faithful into a collective noun of sword-wielders; a crowd that has no hands. The assignment of a quantitative value to the sum of the individuals creates “the Crowd” which transforms the church in the body of Christ into a corporate head. This corporate head then has the right to collectivise "I"s through abstract collectives and representative persona27. We trade human reality for arky unreality.

A possible faithful anarchist cleric…

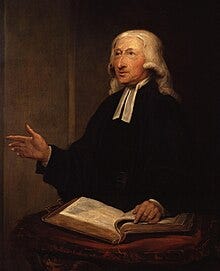

Before we move on, it might be worthwhile to consider a Protestant figure of importance who did fulfil the criteria of the Christian anarchist: John Wesley.

Although he never intended to undermine the Anglican Church28 or oppose the monarchist state in his contemporary England, he maintained that Christianity is available to all as everyone can be a member of the “priesthood of all believers”. This played an important role in his sophisticated ecclesiology where “radical discipleship is always possible”29. This, in turn, gave the Methodists such an explosive and passionate presence within England. Although his death brought deep problems for the Methodists (some or even many of which we might consider unresolved today), that tiny preacher from Lincolnshire may have been the most radical of all to have walked English soils in order to deliver εὐαγγέλιον.

Wesley’s case will need to be dealt with in the future, allowing for greater nuance on the particularities in which those earnest Methodists displayed the piety that turns the stomach of “arch-rationalists” and continues to inspire so many around the world. For now, let’s consider the relation between Christ, Luther, and Müntzer.

Christ’s Opposition to the Powers

In the most unusual agreement in the history of philosophy, the mild-mannered Vernard Eller walked the same path with the obstinate aristocratic philosopher, Friedrich Nietzche: Christ was indeed “that Holy Anarchist”. However, unlike Nietzsche, Eller took up the flag that S. K. carried so far towards a dialectical-smashing understanding of faith to the point where Nietzsche is left without recourse for his anti-Christian sentiments. Instead of viewing Christ or (potentially) the Christian stuck within a dialectic of moral decision, the dialectic itself is smashed - it is by faith that the individual smashes through the problem of aesthetic and ethical considerations of moral decision.

As laid out metaphysically in Concepts of Power, Nietzsche and other moral thinkers - despite their apparent radicalism - still find themselves stuck in the dialectic of moral decision. They fail to break out from the relation between “the universal” and “the particular”, the battle between the Eleatics and the Heraclitans. The terrible temptation of worldly moral decisions means that we are in constant danger of bringing the divine into relation with other options as if it is an option amongst options; God, instead of simply being God, requires that He deliver us moral reason in comparison with worldly reason. If we hold to any type of divine command metaethics, this is unjustifiable - God’s will is preferable because He is God, His will is both good and necessary; if we are asking God to impress us with sagacious arguments prior to the fact, we have already failed to understand the Lord. In this sense, it is the unity of the aesthetic and the ethical in the imitatio Christi, the ethical-religious, that leads us to cut across the dialectic and to break out from under the worldly decisionism that haunts secular appropriation of Kierkegaardian thought. Something happened during the infamous Corsair Affair which turned S. K.’s understanding of Christianity, or, more accurately, what it means for the single individual to be a Christian - the imitatio Christ is key to being Christian as to suffer like and with the Lord is, in essence, the meaning of Matthew 16:24.30

That idea of the imitatio became central to all of S. K.’s understanding of what it actually means to be religious in the Christian sense and what separates the concrete object of faith in Jesus Christ from the “superstitious” theism of other religions. Held at the perfect distance in the anonymity of history, S. K. held that the image of Christ was perfectly between both “overly close” immanence and “overly distant” transcendence, a foot in both worlds - as Hyde notes, “erroneous interpretations of God’s transcendence take two contrary forms: either, God is held “too close” by a religiousness of immanence and thereby encased within the temporal order of creation and made subject to its laws and limitations; or, God is held “too distant,” whereby people fail to recognize God’s intimate interactions with creation”.31 This particular view of Christ and Christianity is central to the radical discipleship that S. K. called his fellow Danes to because the imitation of Christ is “the one facet of Christianity without which the proclamation of all the other facets made a fool of God”.32 While, in his first authorship, the relationship between faith and reality is positive, in the latter, world-renouncing imitation becomes the central goal33; the “negative concept” of Christ becomes an inspiration for the individual and poses itself qua perfect example - against the living faith of the believer. The prototype [Forbillede] reveals God’s image [Billede] to us in a way we can understand - but, paradoxically in a way which shows the destruction of “the ethical” in the leap out up and over into the ethical-religious, the object of faith becomes impossible to imitate in totality. If it was possible that we could take up the mantle of Christ with our own hands, there would be no need for Christ to act as the prototype - we would just turn to other believers for the perfect inspiration and dismiss the need for the object of faith.34 Incidentally, this was central to S. K.’s rejection of Catholicism in particular: “to imagine that humans could become perfect and like Christ, thus usurping the role that belonged only to Christ”.35

When a man like Bernard of Clairvaux or Pascal, both of them significant characters let such a confusion go undisturbed as the Pope’s calling himself Peter’s successor [Eterfølger] (and thus nonsensically parodying the imitation [Efterfølgelse] of Christ), there is still the question of whether this is connected with their wanting to coddle themselves or their perhaps unconsciously and with instinctive cunning refraining from risking what would of necessity come to be martyrdom, a bloody martyrdom.36

Whether this is a fair critique of “popery” is one thing, but this shows the extremity of the contradictory demand of Christ qua prototype: we should all hold the image of Christ, up to the point of taking on the cross for the faith, but even the slightest claim that one is like Christ is to abandon the imitatio and turn Christ into the concrete but restrictive concept of “the ethical”. That constant tension between the conscious, existing individual and the prototype of Christ is the dialectical tension of faith qua faith; any attempt to assert a complete system of doctrine or a figurehead is an attempt to shield the believer from “the intrusions of dialectics”37 and holds faith at as an object separate from the believer as opposed something that causes the heart to beat, the blood to flow, and the will into this world. Nietzsche’s accusation of “life-denying faith” falls flat; only through Christ can one find oneself as an individual who understands their life whilst also remaining free of the restriction of “the ethical”.

Christ and the political

But how did Christ treat “the political”, “the numerical”? According to Jacques Ellul, “through irony, scorn, non-co-operation, indifference, and sometimes accusation”.38 When we take the imitatio seriously (and we ought to take it seriously, because to deny to do so would mean to show “evidence that someone's actions are unimportant or irrelevant to their being Christian”39) we do not hold Christ as “a cheap Christ”40 whose blood was spilt so that we might turn away from Him, but whose redemption allowed us to freely choose to follow Him into the dark.

“Lord Jesus Christ, you did not come to the world to be served and thus not to be admired either, or in that sense worshipped. You yourself were the way and the life—and you have asked only for imitators. If we have dozed off into this infatuation, wake us up, rescue us from this error of wanting to admire or adorningly admire you instead of wanting to follow you and be like you.”41

No longer do we hold Christ as a “great teacher” (as if that is praise) or a “revolutionary thinker” (as if that is praise) or as “an ascetic sufferer” (as if that is praise) - God is praised on the sole account that He is God and the imitation of Christ is held because His sacrifice, His guidance, offers us the necessary, unreconcilable will of the Lord in this world as a path, as footprints in the sand, that we can follow. Christ knocks at the door (Revelation 3:20), but shall we follow Abraham in replying “here I am!” to his call? This, for S. K., was the central knot of the Christian life and the “postpolitical” calling of Christ - it is not a political stance of particular, crowd-constructing dicta that is handed down immanently, but a call to transcend, to become oneself, in the image of God and the prototype of Christ. We must become contemporary to Christ in his obstinacy for “the political”.

“By becoming contemporary with Christ (the exemplar), you discover precisely that you don’t resemble it at all… From this it follows, then, that you really and truly learn what it is to take refuge in grace.”42

My reader, a less indulgent writer might now lay out the deliberation between Luther, Müntzer, and S. K.’s particular understanding of Christ for you. However, I won’t; instead, I ask you to reflect on what is being said here and how Christ, in His perfection, in His necessity, compares to the images I have presented above. And when you deliberate in this way, you will find that it is not only Luther and Müntzer who are linked at subjective contingencies against the objective necessity of Christ. A deliberation begins with the negation of the deliberator.

The Folkekirke

“The form of the world would be like - well, I know not with what I should liken it. It would resemble an enormous version of the town of Christenfeld [which was an experiment in Christian communalism].”43

In the wake of the March Revolution, the then-monarchist S. K. found cause for a change of heart. In a moment of epiphanic natural theology, he had seen that the age of monarchy was passing and in had come the age of liberalism. With this came the unyoking of the Lutheran church from the state itself, an opportunity for a great freeing of the Christian message and a chance for Christianity to emerge from under the thumb of the ruling class. In particular, in a moment of falling hook, line, and sinker for the propagandist movement of clerical class, S. K. applauded that the church had (nominally) been transformed into the People’s Church [Folkekirke] - no longer would a figure of immanent worldliness rule over the pastoral and theological needs of the faithful, it would belong to the people! The body of Christ now threatened to take on the role of the church of the people, wherein the Lutheran state church had always existed in opposition to the people prior to that point.44

As Bukdahl noted, the split nature of Danish piety set the scene for this battle. The Moravian church and the Pietists in contemporary Denmark was a tense one: despite both “pietism” and “rationalism” being officially allowed, “the common people” often organised into local bands of radical churches that demanded more than the rationalist Lutheran state church would ever allow.45 There was a possibility, saw S. K., for this earnest faith of “the simple folk” [den Eenfoldige] could be brought into the broader Lutheran church when the power of the state (and, in particular, the power of royal approval46 and the police47 become irrelevant to ecclesiastical matters).

However, although the state church became the people's church, this process did not unfold as S. K. had expected (or, possibly, only hoped). Instead, little changed at all; even in his most pessimistic moments, S. K. had become concerned that a free church in the free state would lose the “corrective” functionality against the evil the state wields through “the sword”, but he didn’t expect that Mynster and his companions would fall into an even more servile position and gave up both their position of power (which seemed entirely reasonable for S. K.) as well as any possibility for theological impetus (which did not seem entirely reasonable). In the wake of the unyoking from the state, the potentiality for radicalism was gone; the church could not become what Denmark needed in a time when individuality was in such perilous danger and, as such, the individual would have to become greater than the collective.

And that, my reader, is where we refer to Fear and Trembling and the idea that some rules must be broken so that other rules might be followed. And, in essence, that is the methodology of Christian anarchism: a willingness to break the rules that make up our social reality so that we might follow a higher rule, a legitimate authority, the one arkys above arky faith. Again, we come back to the feet of Vernard Eller, Christian libertine par excellence:

Arky faith greatly simplifies moral decision making. One escapes the ambiguity and terrible complexity of dealing with actual individuals who always are very much a mixture of good and evil, actual forces and situations that are very much the same way. Now one can think in terms of homogenous arky power-blocs that clearly classify into either good or bad; moralizing can be done sheerly by knee-jerk reflexing. So “pacifism” (of whatever character) is good and anything that is not pacifism is “evil warmaking.” A capitalist U.S. government is bad; a socialist Sandinista government is good. “Masculinity” is bad; “femininity” is good. The Moral Majority is bad; the National Council of Churches is good.48

As Abraham, Jeremiah, and Christ have shown us, sometimes there is a teleological suspension of the ethical; it is too simple to hide away in the comfort of “the Crowd”, where there is only untruth; it is too simple to hide away in the subjectivity of aestheticism and pretend that “isolationist homesteading” and the like is anything more than a childish fantasy, a hallucination of a new monastery where you are your own God and church; Christian anarchism requires something altogether far more difficult - to have simple faith in a world which hates it, for even if Christianity is torn from the breast of Christ by Constantine or the Nazis or the Putinists or the evangelical right, “Christianity is indifferent toward each and every form of government; it can live equally well under all of them”.49 The individual shall rise out from the universal, not like a phoenix from the ashes but like a whisper in the desert, and assert that Christ is King - above the state, above the society, above the church.

At this moment, we hold for one final piece on this topic: a fifth and final part where we explore the radicalism of faith in the most radical of all actions: foot-washing. Until then, we look at the memory of Menno Simons for inspiration:

“…the true church may be known [by] a frank, unreserved, faithful confession of Christ's name, will, word, and ordinance notwithstanding all cruelty, tyranny and fierce persecution of the world. (Matt. 10:32; Mark 8:38; Rom. 10:10). But where one is Papistic with the Papists Lutheran with the Lutherans, Interimistic with those who accept the Interim; where the Papal doctrines or ceremonies are now abolished and now again adopted, where there is dissimulation according to the command and order of the government - what kind of church this is may be judged of those who are enlightened by the truth and taught of the Spirit of God.”50

To read the other pieces in this series, see below:

Kierkegaard and the Common Man, Kindle location 112, J. K. Bukdahl

Especially in his groundbreaking work on Kierkegaardian sociality and Anabaptist theo-philosophy, Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship

The Theology of Anabaptism, p. 9, R. Friedmann

Almost any Protestant commentary on Anabaptism would suffice here, but the essay "The Young Karl Barth's Critique of Anabaptism", A. Neufeldt-Fast, from The Church Made Strange for the Nations: Essays in Ecclesiology and Political Theology, p. 66, ed. P. G. Doerksen and K. Koop offer a very useful insight into the evolving thought of one of the most important Protestant theologians to have ever lived.

Anarchists, fittingly for their opposition to formal academic establishments, have historically struggled to present academically responsible accounts of radical Christianity in a way that doesn’t reduce the theologies of the Anabaptists to secularized demands for Christian fealty to “the cause”. For one example, see “Anabaptist movement”, S. Marik, link

Christian Anarchy: Jesus' Primacy over the Powers, p. 37, V. Eller

Being and Nothingness, p. 87-118, J. P. Sartre

Menno Simons: His Life, Labors, and Teachings, p. 10, J. Horsch

Ibid., p. 12

"Does a Human Being Have the Right to Let Himself Be Put to Death for the Truth?" in "Two Ethical-Religious Essay", by H. H. from Without Authority, p. 72, S. Kierkegaard

"Is the State justified, Christianly, in misleading the people, or in misleading their judgement as to what Christianity is?" from The Instant, no. 3, June 27th 1855, from Attack upon "Christendom", p. 132, S. Kierkegaard

Menno Simons: His Life, Labors, and Teachings, p. 40-41, J. Horsch

"Love, Hate, and Kierkegaard's Christian Politics of Indifference", R. A. Davis, from Religious Anarchism, p. 86, ed. A. Christoyannopoulos

Christian Anarchy: Jesus' Primacy over the Powers, p. 37, V. Eller

While this is by no means a celebration of the violent actions of the faithful in early Protestantism, we do wonder why Luther’s own willingness to wield the sword should be an acceptable position in the history of Protestantism in comparison to the unacceptable position of the underclasses in the Peasant War.

JP III 1846-1847

JP VI, 6255

JP VI, 6727

The Peasant War in Germany, ch. II, F. Engels

Christian Anarchy: Jesus' Primacy over the Powers, p. 38, V. Eller

Ibid., p. 37-38

Violence: Reflections from a Christian Perspective, p. 103-104, J. Ellul

Quoted in Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship, p. 265-266 V. Eller

Anarchy and Christianity, p. 64, J. Ellul

Christian Anarchy: Jesus' Primacy over the Powers, p. 27, V. Eller

Ibid., p. 50

The Radical Wesley: The Patterns and Practices of a Movement Maker, p. 166, H. A. Snyder

Ibid., p. 13

Kierkegaard and the Common Man, location 1103, J. K. Bukdahl

Concepts of Power in Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, p. 84 J. K. Hyde

Kierkegaard and the Common Man, location 1291, J. K. Bukdahl

"On the (Dis)Continuity in Kierkegaard's Understanding of Faith", G. Schreiber, from Kierkegaard in Context: Essays in Honor of Jon Stewart, p. 7, edited by L. C. Barrett and P. Šadja

"Imitation and contemporaneity: Kierkegaard and the imitation of Christ", p. 3, J. Cockayne

‘Bernard of Clairvaux: Kierkegaard’s Reception of the Last of the Fathers’, in Kierkegaard and the Patristic and Medieval Traditions, ed. Jon Stewart, Aldershot: Ashgate 2008. pp. 23-45

JP II 1930

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 31, J. Climacus, tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

Anarchy and Christianity, p. 71 J. Ellul

"Imitation and contemporaneity: Kierkegaard and the imitation of Christ", p. 1, J. Cockayne

Judge for Yourselves!, p. 189, S. Kierkegaard

Training in Christianity, p. 234, S. Kierkegaard

NB6:3 (ed. Cappelørn et al., 2011,9)

The Book on Adler, p. xxv-xxvi, S. Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard and the Common Man, l. 112, J. K. Bukdahl

Ibid., location 337

"Is the State justified, Christianly, in misleading the people, or in misleading their judgement as to what Christianity is?" from The Instant, no. 3, June 27th 1855, from Attack upon "Christendom", p. 132, S. Kierkegaard

"Medical diagnosis" from The Instant, no. 4, July 7th 1855, from Attack upon "Christendom", p. 140, S. Kierkegaard

Christian Anarchy: Jesus' Primacy over the Powers, p. 26, V. Eller

JP IV 4191

Menno Simons: His Life, Labors, and Teachings, p. 31, J. Horsch