A Pessimist's Stance: Armed Neutrality

Understanding the fallen world through the eyes of the faithful

“I trust to God that in His mercy He will receive me as a Christian.”1

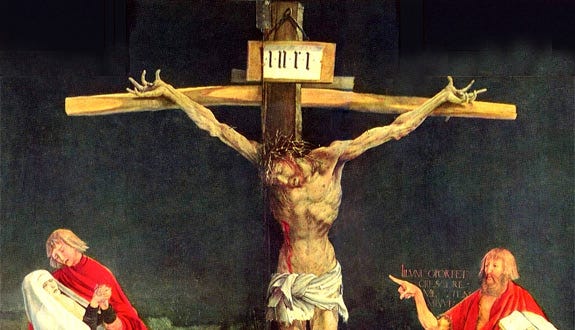

Taking up a pessimistic stance against the word is a difficult notion to explain, let alone justify. In a way, Kierkegaard would say that it is unexplainable, unsayable in a very Wittgensteinian sense; “a system of existence is impossible”2, so all we can do is present an image, the ideal (incidentally, the same word in Danish: billede) that we can hold in distinction with our own lives. Through this necessary dialectic of life, comparing my existence both with the “my existence in potential”, i.e., the unrealised future and the Prototype [Forbillede] of Christ, I discover something that can be meaningful for me, for my existence. In this radical attack on universalizability, we set the stage for an exploration or “deliberation” of existence in lieu of a “System” which would give us the answers to our lives - as if such a thing could be presented.

In an exercise in self-reflection, S. K. had written the essay “Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom” in order to answer the problem of what precisely his position was. As with all Kierkegaardian writings, we’re justified in taking a somewhat skeptical view of just how much he had actually shared about himself in this essay; as with the other two self-reflective works3, there are credible reasons to suggest that even these personal essays on the subject of “Søren Kierkegaard” himself was shrouded in irony!4 Still, the statement made in “Armed Neutrality” is still an important one for orienting a Christianity which grounds itself in the subjective, in the pessimism that Christ and Paul personified: if we are truly to be “not of this world”, then let us take up our shield of faith and sword of the Spirit (Ephesians 6:16-17) in our pessimistic indignation and difference. Assume a position of armed neutrality.

Demanded the Impossible

In 1992, the historian of anarchism, Peter Marshall, published his magnum opus: Demanding the Impossible5. An eclectic and disparate collection of stories about various anarchist tendencies, he offers a brief but superficial exploration of the history of Christian movements which are, at least in appearance, anarchist in nature:

At first sight, it may seem strange to link Christianity with anarchism. Many of the classic thinkers, imbued with the scientific spirit of the nineteenth century, were atheists or agnostics. Like the philosophes of the Enlightenment, they tended to dismiss organized Christianity as part of the superstition and ignorance of the Middle Ages. They saw the Church aligned with the State, and the priest anointing the warrior and the king. For the most part, they thought Christianity taught a slavish morality with its stress on humility, piety, submission. The traditional image of God as an authoritarian father-figure was anathema to them, and they felt no need for a supernatural authority to bolster temporal authority.6

I will allow you, my reader, to peruse the rest of the chapter on your own. As an introduction to Christian anarchist thought, it does at least present the case as something that occurred and continues to occur throughout history - aside from that, it is a little unfair and a little too secularly dismissive to really build a case.

This would be a strange aside, of course, if not for something particularly Kierekgaardian that I have in mind: Christianity is not merely demanding the impossible, but we are also demanded the impossible7. If there is indeed an Absolute that is “out there” somewhere, then we should know that God’s existence implies that the stakes for what the Christian places upon themselves in terms of moral demands is beyond the “measuring-stick” of humanity: there is a danger that the love and power of the Almighty is replaced and subverted by the failure of humanity.8 In that way, it is no mystery why Marshall could not recognize the power of Christian anarchism (or thought of Christianity in general as a kind as the Nietzschean facsimile as a “slavish morality”): he did not understand that it is not a human demand placed on reality - as if we could ever expect the individual to overpower reality itself - but rather a demand of the non-human, of the “infinitely qualitatively different”, that sets the agenda for Christians. In S. K.’s particular approach, this mismatch - the finite human in the face of the infinite God, who Himself had became finite qua the truth within time - is the source of all Christian thought. If we do not understand that before God we are always wrong, we cannot take one step as a Christian.

Suffering as holiness

“[Christian piety is] a militant piety (engaged at two points, first in oneself with oneself in order to become a Christian, and then with the world's opposition and persecution because one is a Christian) is Christianity or being a Christian.”9

Christianity is no stranger to irony10: Christ as the God-Man, parables, a love letter11 disguised as a codex of law, etc. Similarly, it is no stranger to militant language: the miracle of Joshua 6:1–27 where some shouting, a horn, and divine intervention destroyed the formidable defences of Jericho, the armour of faith illustrated in Ephesians 6:10-18, or even the particularly on-the-nose practices of the Salvation Army. In this way, Christianity’s relation to “the world” is thoroughly ironic: the world is recognizable in its fallen nature, but Christianity’s sabre(of-the-Spirit)-rattling response is not one of conquest, not one of domination, but one of love. “The Sword” we wield is one of Spirit - total comfort in our combined acceptance of our finitude, realisation of the infinitude of possibility, and the acknowledgement that we are the beacon in the dark, the “sons of God”, by choice and through action. “The Sword” the Lord wields is not God's “form of justice or redemption”, but a sign of grace “by keeping God's fallen creation in existence (however destructive sin itself is) with a view toward the God-intended redemption of the fallen creation”12. But this presents us with the contradiction which has caused Christians as great as even Augustine13 to waver…

“The one who presents this picture must himself first and foremost humble himself under it, confess that he, even though he himself is struggling within himself to approach this picture, is very far from being that. He must confess that he actually relates himself only poetically or qua poet to the presentation of this picture, while he (which is his difference from the ordinary conception of a poet) in his own person relates himself Christianly to the presented picture, and that only as a poet is he ahead in presenting the picture.”14

In remembering “this picture”, we remember the deliberation: Christ’s example qua the perfect human individual is the basis our example. In the ironic militancy of Christ and the would-be cross-bearers, the example is set on the path to Golgotha: as in Matthew 5:38-40, Christ calls us to reject violence. The temptation at this point is to reduce Christian to only existing “as a teaching, as a doctrine”15; to adopt Christ’s majesty simply because He is a great teacher, which sounds like some perverse form of Ebionitism. Instead, let’s examine why nonviolence becomes necessary when we hold Christ in deliberation with “the universal” of humanity.

Following from Jacques Ellul, one of the true great Kierkegaardians, he examined the role of violence within human societies. His book Violence presented five laws which seem to pervade the use of violence within societies by necessity: continuity, reciprocity, sameness, violence begets violence, those who use violence always seeks to justify it and themselves16. A substantial analysis of these laws will be examined in the future, but let us speed ahead to Ellul’s conclusion: violence is necessary for the world, hence why we can’t find a society that has no engaged in the use of violence - especially within the secular world. And in rejecting this necessity, through the gift of Christ giving us a chance to evade the necessary, e.g. the violence of human society17, we are free from the world. Here is the Kierkegaardian deliberation, here is genuine holiness: in following Christ into the seemingly impossible for humanity, we become impossible, the unrecognizable; a Christian will follow Christ over the necessity of humanity into the liberty wherewith Christ has made us free (Galatians 5:1).

Swimming in the Vortex

Of course, the above isn’t easy. It’s very difficult, in fact; the call to take up the cross (Matthew 16:24) has actually been taken up by very few in the history of Christianity. This might lead us to say that there have been very few Christians in the history of Christianity, in fact; that those who were prepared and followed through will the ultimate sacrifice for truth were the only ones to really show their mettle in the way that Christ expected them to. If that is the case, then there is a concern about how narrow the gate (Matthew 7:13-14) actually is and what it would mean to cross it.

But why is it so difficult? Here, we can turn to a piece of S. K.’s often neglected sociology: society as a vortex that drags down and swallows the Ideal18. Here, we are in danger of accidentally falling into Thatcherism; does Kierkegaard, whilst holding himself as (at least an aspiring) Christian, really say there is no such thing as society Absolutely not: Kierkegaard’s Christian atomism is far overblown, which leaves us with a dialectical puzzle here. It is not that society is impossible, but rather that society is impossible in liberal society.

In understanding S. K.’s concept of repetition (and this short piece by M. G. Piety really does make the sometimes confusing topic very straightforward), we must understand that humanity needs to repeat its interests and engage in upbuilding through that repetition. In short, through the process of identifying and repeating our commitments to certain concrete ideals, we develop ourselves as individual selves. So, why is that impossible in liberal society? Due to the problem of “closeness”19: without a “separating factor” that holds our personal interests apart from those around us, we get too “close” to others within society that forces the collapse of the I-Thou relationship20 and only turn to one another in “chatter”. Here is where our pessimism kicks in again: this aspect of liberal society shows us that secular radicalism has nothing to offer us; without the “separating factor”, it will always collapse into the immediacy of “chatter”. If we are to escape the vortex, we will again need to adopt Christ’s indignation with humanity21 and reject necessity.

In escaping the vortex of liberal society that forces us into the swirl and robs us of our chance of becoming a self, we can relate to “the other” and overcome this necessity. When the world has nothing to offer us on its own, only through the relation with Christ, the “separating factor” between individuals, can we stand on our own two feet and become the brake on the vortex - through the power of Christ’s infinite negation; the divine “no!” against society’s vortex.

The Christian qua time traveller

If you have followed everything that has been said so far, you might be feeling a little pessimistic about the possibility of change. That’s understandable - we are discussing two of the great Christian thinkers when it comes to pessimistic assessments of the society we live in, so it’s only natural to assume that it is hopeless. But neither of them actually saw the challenge as insurmountable - at least in no small part because “with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26).

The solution is to turn against the conventional understanding of social change: creating “sagacious” systems of logic which predict the inevitable utopian future that lies before us, like the Holy Land on the other side of Mount Nebo. These theories, inevitably like Moses, seem to have dropped dead on seeing “the other side” of the mountain and capitulated into a far cry from their previously impervious intellectual bedrock22. This is a mixture of two concepts from S. K.’s work: “the despair of defiance”23 and “the future present”24. In attempting to escape our earthly bonds, we construct elaborate systems of existence disguised as systems of logic: we assume the merely abstract can have something meaningful to say about the actual problem of existing and moving into the future as an existing being25 - but “a logical system can be given... but a system of existence cannot be given”26. This system of logic is placed into the life of the existing being and found to be incongruent; we can’t possibly live our lives out like this, so the scripture must be amended, the theory must be refined, the praxis must be halted until we are ready - we cannot go into the water until we have learnt everything there is to know about swimming!27

In this way, the solution isn’t to “go beyond” our current position, but to turn back, to “cut to the bone” of Christianity in order to find what we must do. In becoming a Christian who follows Christ, there is a commitment to “clear the middle terms” and become contemporary to Christ in His mission28. This drive backwards to the dialectical high-point of Christianity, i.e., in Christ’s presence, to understand how we should act. And when we know how we should act (which might be summarized in Hauerwas’ words in “What You Believe About Jesus is Your Politics” in a fantastic interview with Tamed Cynic), then we act exist in “the Moment”: our finitude is recognized, our ability to freely act is grasped, and we can consciously choose how to act in our relation with God, the other, and the world around us. The Christian must travel time itself in order to genuinely become a Christian: first, to the foot of a cross in Golgotha, and then back into the present in order to act. Draw strength from the memory of Christ and the power of the Spirit, allowing us to do great things because “with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26).

The negation of positivism

S. K., in his prophetic and pernicious way, noticed something rather worrying about the direction of the Present Age: a deification of positivist thought, scientific reason, and “systems of logic”. While not opposed to these ways of thinking (indeed, S. K. was apparently a talented mathematician and physicist in his youth and had almost taken up his studies in one of those fields, along with the repeated notion in contemporary Kierkegaardian studies that he was by no means an irrationalist29), he didn’t view them has having any obvious superiority over different ways of thinking.

And this became central to S. K.’s thought: becoming a Christian demanded ending the reliance on positivism, but without necessarily discarding it outright30. It becomes a matter of context, of relation; how do we prioritize the knowledge we gain from the natural sciences and other positivist endeavours in relation to our lives? As the sciences are necessarily dealing with “the ultimate irrationality of contingency”31, how are we meant to integrate that information with knowledge of the necessary and eternal? In even sharper terms: what precisely could scientists ever tell me about how I ought to live my life?

This is especially pernicious in S. K.’s mind when he sees the replacement of the clergy as the ideological guard dogs of early bourgeois society with the scientist and the doctor:

“Pastors are no longer spiritual conselors - physicians have become that; instead of becoming another man by means of conversion one becomes that nowadays by water cures and the like - but we are all Christians!”32

“…in our day the physician is the spiritual advisor. People even have a perhaps groundless anxiety about calling the pastor, who quite possibly in our day would talk somewhat like a physician anyway - so one calls the physicin… For what is an anguished conscience?” And the physician answered: “such thing does not exist anymore, is a reminiscence of the childhood of the race.”33

A rousing speech for people to question the very thing they seem to prize most highly above all now that religious values have been discarded, their lives, is all the more rousing when we realize that S. K. was himself a rather sickly man:

“My energies, that is, my physical energies, are declining; the state of my health varies terribly. I hardly see my way even to publishing the essentially decisive works I have ready… It is my judgement that here I am allowed to present Christianity once again and in such a way that a whole development can be based on it.34

A full examination of S. K.’s understanding of the unjustified prominence of scientific, and particularly medical, knowledge would need more space than we can justify here. But the important part is: in his sickness, we see a man state that he is not given anything of note by the scientists and physicians about how he should live his life. The anguished conscience (which, due to S. K.’s particular Lutheran commitments, are essential for faith35) is something to be discarded, something to be removed from the concept of “human requirements”: we cannot comment on it positively, therefore it should be discarded.

Interestingly, much like Wittgenstein later on, S. K. wasn’t entirely opposed to this kind of thinking: in particular, he was deeply suspicious of metaphysics that claimed a bit too much, got a little too bold, got a little too sloppy. In this sense, the logical positivists and Bertrand Russell were right to doubt what could be expressed in metaphysics - however, their strong reaction against metaphysical study was unjustified: although accepting of the mistrust of metaphysics, he rejected the "leap" to the erection of a scientism which rejected what was still useful in the metaphysical tradition36. In that way, a hard swinging retreat away from metaphysics on account of inability to knowingly tread with certainty was just as much of a “leap” as Bishop Adler’s fantastic and presumably illness-induced vision of Christ as the divine anti-Hegelian37. Instead, we can “poke” at the edges of what is knowable, “poke” to investigate the “edge of reason”: we can find the “negative concepts” of God which then inform the way we see ourselves, our actions, and our drive towards something38.

In this sense, we come to the pessimist knot in S. K.’s anti-positivism: it is because there is an eternal negation, God’s Almighty “no!” that cries out across existence, that we understand ourselves in relation to something. Although S. K. teetered on the edge of cognitivism and noncognitivism as well as rejected both natural theology and any other “objective” proof for God in a wider sense, he still believed that pursuing these avenues was worthwhile, worthy of discovering something even though “hardship is the road”39 and the discovery at the end, in its negation of the human subject, is not something positive but rather a negation and humbling of our inappropriate sense of infinity.

Pattern, Paradigm, Prototype

“The one who presents this picture must himself first and foremost humble himself under it, confess that he, even though he himself is struggling within himself to approach this picture, is very far from being that. He must confess that he actually relates himself only poetically or qua poet to the presentation of this picture, while he (which is his difference from the ordinary conception of a poet) in his own person relates himself Christianly to the presented picture, and that only as a poet is he ahead in presenting the picture.”40

The dialectical nature of S. K.’s understanding of Christianity as an historical phenomenon leads us into the tight “knot” of choice: do we accept Christ’s message as Christ’s message?

Understanding the dialectical relationship between Christ’s ministry and contemporary Christian society, we should at least notice a difference of some kind. I am not going to lay out an exhaustive list of these differences, but the most notable one should be that “religion” is something ideological, something of an identity in this Present Age; this would not have been the case in times gone by, where a Christian was identified by their commitment and praxis as an individual being within a collective. This sets the challenge before us: is it greater to follow in Christ’s footsteps or to accept the status quo today? Which Christianity is greater?

This, then, becomes a matter of action for the Christian: Christ’s message - whether from His own mouth or via the Apostle - is one which demands we do something, we can’t simply hear it and nod along with a bourgeois agreement that does little to actually put that agreement into the world. Instead, the steadfast holding to Christ’s mission is not neutrality qua quietism, but “Armed Transcendence”41; we shall take up a position of meekness, surrender, and servitude to the other in becoming unrecognizable. If we do hold that Christ was perfect and that His mission was necessarily played in such a way that it was necessary for it to have been as such, then the imitatio Christi is necessary for us in order to take up our positions as being judged as Christians. The fear and trembling of the God-relationship should be held exalted over all as the hope that guides us into the unknowability of future existence, which may or may not include the blood of the martyrs to be spilled - pagans also died for an idea, but they lacked an inward relation to the Eternal to make their sacrifice worthy, so what does that mean for the Christian in following Christ?42 In following Christ, it is essential to view Christ as the negation of our worldly fears: the Pattern, Paradigm, and Prototype of the Lord is not necessarily the path we must literally walk, but the negation of the paths we shouldn't. As the difference between the path the Pharisee and the Good Samaritan walked was visibly the same but invisibly different43, we must learn to see the invisible: we must learn to distinguish God’s workings in the world from the world’s workings in us. We trace the footsteps in the sand to walk the path of necessity: and hardship is the road because hardship is the road we are destined for (1 Thessalonians 3:3).

As mentioned above, the problem of accepting Christ’s message is in attempting to think beyond sociological pressures - which would include something I am saying, if it contradicts Christ in any way. Can we actually escape our sociological, temporal confinement? Is it possible to break out, “cut to the bone”, and walk amongst the apostles in discipleship? This question requires further thought, something we will unpack in the future.

That Holy Anarchist…

As with so many thoughts concerning Christianity and Kierkegaard, we circle back to Nietzsche, the anti-Christian par excellence. With his usual snappy approach to propose, he took this look at Christ in his most appreciative work on Christianity:

That holy anarchist who summoned the people at the bottom, the outcasts and “sinners,” the chandalas within Judaism, to opposition against the dominant order-using language, if the Gospels were to be trusted, which would lead to Siberia today too - was a political criminal insofar as political criminals were possible at all in an absurdly unpolitical community.44

It is clear how Christ was viewed in the eyes of the iconoclastic German. Christ’s mission, which led Him to the cross, was an act of political significance. While there are certainly those who would like to hide away from the political implications of the religious convictions, it might be best to remember that genuine theological commitments have political consequences of the highest order: the Lord Himself bore them so that we might have eternal life.

But this wasn’t only true of Christ - it would be trivial to list out martyrs or explain the role of martyrdom in the culture of the primitive church. However, for Kierkegaard, in the age of reason, he saw martyrdom as slightly different: instead of coming up against the Sword of the State, he came up against the mockery, cruelty, and ostracism of “public opinion”. But public opinion or democratic self-congratulation cannot be the basis of our thought because the individual - by the grace of God - must transcend the oppression of levelling of a society which wants to drag everything down into the vortex45. Despite the obvious change in the particular technologies we are exposed to, our challenge isn’t all that different to that of S. K.: “public opinion”, as expressed through the press and over social media, doesn’t actually seem to represent anyone’s view of the world. The represented don't seem to exist - who is this person of the "public opinion"?46 In the age of propaganda, S. K. calls us out into the unknown to “cut to the bone”: we will engage in Armed Neutrality in our Armed Transcendence in rising over the represented, “the Crowd”, in order to hold fast to Christ.

The Eternal Infinite Negation

This leads us to the most humbling realisation of the divine, in the gift of faith, for the Christian: just like S. K., I am no extraordinary Christian47. In fact, I am not sure that I will be received as a Christian at all by the Lord. But hopefully, this has made the challenge clear for the aspiring Christian; hopefully, this has made the demand of the challenge actually challenging for the aspiring Christian; hopefully, as S. K. intended to in times gone past, this attempt to understand “armed neutrality” leads us to present a “negative-manifesto” of Christian political theology: not creating theories or systems of existence, but defining the contours of our lives as followers of Christ in the negative, using negative concepts and the eternal “no!” of Christ’s eternal infinite negation of worldliness to lend us the strength to walk as Christians in the footsteps he left behind for us. As I said in the beginning, “I trust to God that in His mercy He will receive me as a Christian.” May the Lord have mercy on me, a sinner.

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 136, S. Kierkegaard

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, vol. I, p. 107, J. Climacus

“On My Work as an Author”, p. 1-20 and “The Point of Vew for My Work as an Author”, p. 21-97, along with other shorter essays such as “The Single Individual”, Point of View, S. Kierkegaard, ed. H. V. Hong and E. H. Hong

Love's Grateful Striving: A Commentary on Kierkegaard's Works of Love, p. 15, M. J. Ferreiras

Demanding the Impossible, p. 65, P. Marshall

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 139, S. Kierkegaard

"The Exposition" in Training in Christianity and the Edifying Discourse which 'Accompanied' It, p. 91, Anti-Climacus, edited by S. Kierkegaard

Ibid., p. 130

Understood as the gap between the appearance of a thing and the thing itself; an ironic relation between appearances and reality which we usually find amusing - unlike this footnote, presumably.

For Self-Examination and Judge For Yourselves! and Three Discourses (1851), p. 51, S. Kierkegaard

Discipleship as Political Responsibility, p. 18-19, J. Yoder

Contra Faustum Manichaeum, book 22, sections 69–76, St. Augustine

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 133, S. Kierkegaard

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 129, S. Kierkegaard

Violence: Reflections from a Christian Perspective, p. 94-103, J. Ellul

Violence: Reflections from a Christian Perspective, p. 127 J. Ellul

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 134, S. Kierkegaard

"Envy as Personal Phenomenon and as Politics", R. L. Perkins, from International Kierkegaard Commentary, vol. XIV: Two Ages, p. 118

Works of Love, p. 56, S. Kierkegaard - yes, the famous Buberian couplet began as a theme within Kierkegaard’s oeuvre!

"The Pessimism of Christ", C. G. Shaw, from International Journal of Ethics, Jul., 1916, Vol. 26, No. 4, p. 473

For two examples, see Ellul in Christianity and Anarchy and Jesus and Marx, where he assesses both anarchist and Marxist movements as effectively dismissing both the core aspects of their intellectual foundations under the slightest pressure, adopting new and contradictory concepts as soon as the intellectual bedrock is frayed, and turning into dangerously incoherent political philosophies-turned-sloganeering before long. Extended assessment of “Christian” anarchist and Marxist movements are shown to be neither Christian nor anarchist/Marxist in any meaningful sense.

The Sickness Unto Death, p. 67-74, Anti-Climacus, ed. S. Kierkegaard

Repetition: A Venture in Experimenting Psychology, p. 137, C. Constantius

"An Introduction to the Problem", from On Kierkegaard and the Truth, p. 7-8, P. L. Holmer, ed. D. J. Gouwens and L. C. Barrett III; Comment on "Kierkegaard's Attack on Hegel", M. Weston, from Thought and Faith in the Philosophy of Hegel, p. 141, ed. J. Walker

Concluding Unscientific Postscript, p. 109, J. Climacus

"Kierkegaard and the Logic of Insanity", M. Westphal, from Religious Studies, vol. 7, issue 3, p. 199 - this line, parodied from Hegel’s “we cannot go into the water until we are sure we can swim”, shows the divide between thought and existence when life, if we remember, must actually be lived and not simply read about.

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 132, S. Kierkegaard

For example: Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship, p. 131-132 V. Eller; "Common People: Kierkegaard and the Dialectics of Populism", from Argument: Biannual Philosophical Journal 11(1), p. 178 R. Rosfort; Kierkegaard: Existence and Identity in a Post-Secular World, p. 35, A. Hannay; "Passionate Reason: Kierkegaard and Plantinga on Radical Conversion", R. Otte, from Faith and Philosophy, vol. 31, no. 2, April 2014, p. 171-172; "Kierkegaard and the Relativist Challenge to Practical Philosophy", P. Mehl, from Kierkegaard After MacIntyre, p. 22, edited by J. J. Davenport and A. Rudd;"Kierkegaard on Rationality", M. G. Piety, from Kierkegaard After MacIntyre, p. 63, edited by J. J. Davenport and A. Rudda

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 141, S. Kierkegaard

Comment on "Kierkegaard's Attack on Hegel", M. Weston, from Thought and Faith in the Philosophy of Hegel, p. 135, ed. J. Walker

Pap. X2 A238

For Self-Examination, p. 201-202, S. Kierkegaard

Pap. IX A227

Love's Grateful Striving: A Commentary on Kierkegaard's Works of Love, p. 19, M. J. Ferreira

On Kierkegaard and the Truth, p. 11, P. L. Holmer, ed. D. J. Gouwens and L. C. Barrett III

"Historical Introduction", from The Book on Adler, p. xv, S. Kierkegaard, tr. H. V. Hong and E. H. Hong

Comment on "Kierkegaard's Attack on Hegel", M. Weston, from Thought and Faith in the Philosophy of Hegel, p. 146, ed. J. Walker

"The Gospel of Sufferings: Christian Discourses", from Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, S. Kierkegaarad, p. 300

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 133, S. Kierkegaard

"The Crowd and Populism: The Insights and Limits of Kierkegaard on the Profaity of Politics", p. 14, J. J. Davenport, from Truth is Subjectivity: Kierkegaard and Political Theology, ed. S. W. Perkins

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 137, S. Kierkegaard

"The Gospel of Sufferings: Christian Discourses", from Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, S. Kierkegaarad, p. 299

The Antichrist, F. Nietzsche, from The Portable Nietzsche, p. 599, ed. W. Kaufmann

Concepts of Power in Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, p. 130 J. K. Hyde

"Kierkegaard on the Internet: Anonymity vs. Commitment in the Present Age", by H. L. Dreyfus, from Kierkegaard Yearbook, 1999, p. 101, edited by N. J. Cappelørn, H. Deuser, C. S. Evans, A. Hannay, and B. H. Kirmmse

"Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom" in The Point of View, p. 129, S. Kierkegaard