Whose Judgement? Which Rationality?

S. K. contra the front pew

Every now and again, you find yourself in the presence of a real orator of theological power. Their appearance breaks through the sometimes fusty, sometimes overly formal, sometimes overly casual character of the average Sunday service, refreshing what is always already there in a way which isn’t a mere flourish into some passing fad or other (2 Timothy 4:1–4) but genuinely stirs the bones of the congregation, sets into motion what was passive and breaks up the mechanical and dreary flow of simple cause-and-effect that typifies the mass society. This person is not recognisable by some objective metric—such a thought would be to develop a formula of proclamation, which is tantamount to misunderstanding the entire effort so poorly that one would possibly not even recognise kerygmic speech if it took flesh and drove them out of the temple—but by a collection of qualities, a family of characteristics, which may or may not be present within different agents at different times. Such is the humorous mechanisation of the Spirit, it seems, ready to subvert the technical demand of modernity by refusing to become an object of science.

Perhaps there is a flair of blood and guts, fire and brimstone, which is altogether a little too impolite for the middle-class comfort of postmodernity; perhaps a story which seems to catch the jagged edges of the congregation’s subjectivities, such is the earnest held there within; perhaps it is merely a presentation of the word without chatter or pomp, disappointingly short for the one who arrived in order to see the show. There is a great deal of variance here, of course, and I have no doubt that you are perfectly capable of bringing your own stories of such a thing to the fore—and, of course, your own stories of the inverse. However, there’s something present within the presence of the real orator that should bring us to pause: how does one exalt the ideal that raises the temperature of a sermon from the comforting churchiness of the preacher-entertainer to the fever pitch of “the offense” (Matthew 11:6) without invoking the temptation to engage in judgment? What would it mean to judge the other qua sinner when engaged in the often poorly-conceptualised act of “correcting” or similar? In a way, what separates judgement from what Paul lays out in Galatians 6?

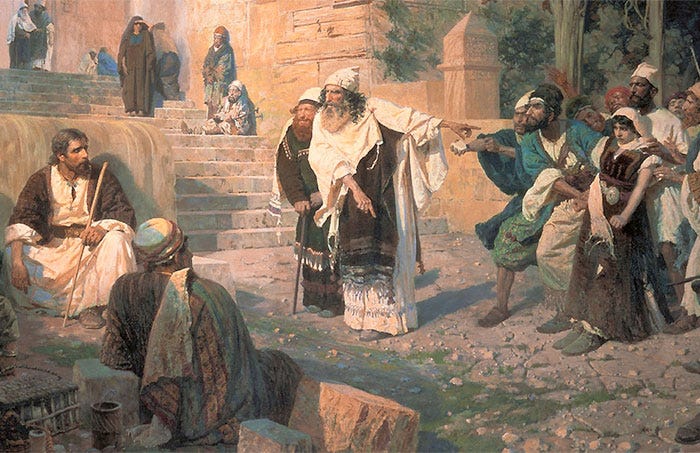

If we are to take Christ seriously—and this is usually accepted by even the most cantankerous of Christians—when he guides us on the path to freedom from the desire to judge the other, how does one hold up the mirror1 without collapsing into stone-chucking (John 8:7)?

As a preliminary, the words of a saint:

By this phrase “armed neutrality,” especially as I explain it more and more precisely, I think I am able to characterize the position I intend to take and have taken in throwing light on Christianity or what Christianity is or, more accurately, what is involved in being a Christian. Naturally, this cannot mean that I want to leave undecided whether I am myself a Christian, aspire to it, fight for it, pray about it, and trust to God that I am that. What I have wanted and want to prevent is that the emphasis would in any way be that I am a Christian to an extraordinary degree, a distinguished kind of Christian. This I have wanted and want to prevent. But what I have wanted and want to achieve through my work, what I also regard as the most important, is first of all to make clear what is involved in being a Christian, to present the picture of a Christian in all its ideal, that is, true form, worked out to every true limit, submitting myself even before any other to be judged by this picture, whatever the judgment is, or more accurately, precisely this judgment—that I do not resemble this picture. In addition, because the task of producing this ideal picture is a work in which emphasis falls upon differential qualifications for being able to do this, especially since it is to be done in relation to the manifold confusions of modern times, I have chosen for purpose of designation the words: neutrality and armed.2

S. K. stressed at length that the image of the “extraordinary Christian” is not one that he sees himself as embodying—so, therefore, he is not the one to cast judgment against the other or reform the church, but rather only to hold up “this ideal picture” that offers to intercede on his behalf. Indeed, the very presence of “the offense”3 itself, hanging in the ugly beauty of an unremarkable man that was slaughtered at the capricious hands of the state, is enough to do more than any windbag en gros ever could.4

But where is this extraordinary Christian? Who is this person who can cast the first stone? Let us consider this universal question in the mode of a particular particularity—the monastery:

“It is a special sort of a retreat we should make. Back to the monastery—the question must be brought back to the monastery from which Luther broke out (this is probably the truth) [...] The monastery’s error was not asceticism, celibacy, etc. No, the error was that Christianity was reduced by allowing this to be regarded as pertaining to extraordinary Christians—and then all the purely secular nonsense as ordinary Christianity. No, asceticism and everything belonging to it is merely a beginning, a condition for being able to be a witness to the truth. Therefore the swing Luther made was in the wrong direction [...] Consequently the error in the Middle Ages was not the monastery and asceticism but that basically the secular mentality had conquered in the monk’s parading as the extraordinary Christian.”5

S. K. seems to be leading us in the direction so as to suggest that a person cannot possess faith “in an extraordinary degree, since the ordinary degree is the highest,”6 and, when one is in possession of this ordinary degree, one would be aware that power is not exercised in the thirsting desire to cast judgment against the other.

At this point, we can pause for the hilarious self-exposure of the play-Christian: if the notion that one should not judge the other as an existential expression of faith proper brings about anger, fury, calls for practicality and realism by the upset counterpart of our loafing musings, then it appears that one falls short of the ideal—“it’s not my Christianism if I can’t throw stones”, if you will. However, already here, we should be aware that this is also judgement: this sets the boundaries for Christ’s love, where I, my reader, have misled you down the garden path in (falsely) taking up the mantle of the “extraordinary Christian” (oh so very falsely) in order to drop my little stones onto the heads of those below the balcony, as if sin were not to so impolite as to reach up into my baronial castle that fails to protect me from secularity. No, my reader, I’ve misled you—I have misstepped and you would be wise not to elevate the footprints in the sand that I have left for you.

Maybe, then, there is something more for me to do: somewhere else for me to go and another path that, whilst obscures, has surely been trodden before. Instead of, perhaps, grasping that delicious aesthetic temptation of the will to taunt the other with a false judgment, just perhaps I am being drawn unto some point where “chatter” is not the aim at all: it is the reception of the word that only finds practical expression.

Here, my reader, we find ourselves learning to praise the characters that we have so often heard gone without a single word of praise in the services that haunt the background noise of our thought: the Ancient Israelites, sinful, impudent, and occasionally faithless as they were. This is not to praise sin—the work of liberal theology has already been done—but, rather, to recognise that the vessel is as important to the quenching relief of water for the man in the desert as the water itself: the sinful backdrop of the Hebrew stories, those people “living life”, is itself a signal to the faithful to maintain faith even in the times where faith seems to be even more vanishingly invisible that it already is.

While Christ shines as the transfigured contingent arrival of a necessary truth, the mode by which God’s eternal goodness came into being by way of a man, we are first handed figures who either sin bravely against the Lord or participate in their upbuilding by ways which the external world sees as sin: for all the crowd that would have turned against a father ready to sacrifice his son and forced him to turn back, the one sanctified in the fire of the Lord recognises their particularity in a way that the other may not (Genesis 22); for all the despair that fell upon the Hebrews in Egypt, the one who bolstered to guide them out into the desert himself was an impertinent and disobedient leader (Numbers 20:11); for all the sin that seeped into the society of the Israelites, they had survived to walk sinfully God’s path of liberation from sin7. The notion of goodness that shines through the sinful as is illuminated in the fractured glass of the sinful social life is the necessary corrective for our arrogance: we are, like shards that insist they remain a pane, those same sinners—and our first task is to discover that qua the infinite qualitative difference as our lives—as my life—in comparison to God—my God, my Saviour, the One Who died for me. To first turn to the other and accuse him of sin is an error in thinking that I am “extraordinary enough” to offer the final judgement against the one that God has not and, indeed, lends power to in the way that only One Who is omnipotent could.

In the quiet repose of the one turned towards God in prayer, that same emergence—of the individual realising themselves qua self for the first time in the way that they always already ought to be and always already are8—occurs again: the sinner can begin to swim alone through my own power and, by way of God’s help, I am pulled from the water to breathe again.

For Self-Examination and Judge For Yourselves! and Three Discourses (1851), p. 50-68, S. Kierkegaard

“Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom” in The Point of View, p. 129, S. Kierkegaard, emphasis mine.

Philosophical Fragments, p. 64, ]J. Climacus]; Works of Love, p. 59, S. Kierkegaard; “The Exposition“ in Training in Christianity and the Edifying Discourse which ‘Accompanied’ It, p. 94, [Anti-Climacus], ed. S. Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard and the Question Concerning Technology, p. 32, C. B. Barnett

JP III 215, emphasis mine.

Concepts of Power in Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, p. 144, J. K. Hyde

“The Meaning of Kierkegaard’s Choice between the Aesthetic and the Ethical: A Response to MacIntyre”, J. J. Davenport, from Kierkegaard After MacIntyre, p. 105, edited by J. J. Davenport and A. Rudd

“Every Good Gift and Every Perfect Gift is from Above II”, from Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 in Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, p. 154 S. Kierkegaard