Towards a Theory of the Christian Deed

A Literary Review in short - part IV.ii

Fundamentally, politics—or, at the very least, the victory of politics—comes in the imposition of a particular way of life onto a given population. In the technological age that we have emerged into, the nature of this victory is often totalising and everpresent: first, as an institution which imposes rule onto a given population; second, as a dictator of propaganda, providing the bounds for what constitutes a respectable opinion; and, thirdly, as a violent arm that enforces its will when people step outside of these provided bounds.

As a part of this, this also involves the creation and management of the counter-crowd as well—developing respectable avenues for protest that give malcontents ways to engage with the state in a way which absolves them of considered thought on their own part and, instead, can pick up the pre-approved notions that allow for suitably respectable protest.

Of course, whilst we occupy the balcony, my reader, it would be appropriate to note that these malcontents, malcontent in their malcontented ways-of-life, are defined by their inability to “fit into” society and the role that it allows for them—in some way, as a product of some particular meeting of the ideal and the material, they have found that they exist outside of the social order1 and compelled by the conditions of their existence to take up arms against it. Indeed, a great many political debates have circulated around what constitutes the acceptable bounds of the “in-group” and the acceptable “out-groups” which sit at the bounds—or, as we begin in leisurely descent onto the Road, the development of the shape of the crowd and the signifying of both the “anti-crowd” and “the favoured oppressed”2. NaTo illustrate, my reader, think about the kind people who sit at the periphery of “friend” and “enemy”, often in a warring situation: the Russian forced conscript, the Ukrainian Nazi; the reluctant IDF enrollee, the Palestinian Islamist extremist. Hopefully, my reader, at least one of these examples has raised your hackles in realisation of some “other” that sits outside of the acceptable narratives we are handed by the psychopolitical structures of our lives. If you should ever want to quickly bring a party to an end, playing your own version of this little game is usually an excellent first step on how to lose friends and alienate people. Without this presumption of a friend who wields the authority to dictate to us our enemies, though, it appears that these figures—reluctant and blameless or willing and guilty—may merely be our friends, our neighbours, who have been turned against us without reason. Navigating around this, my reader, then is the ordeal that besets us all—and such was the hardship of the Samaritan.3

In that sense, I offer a different hypothesis to the one that circulates around the creation and destruction of these groups: the soothing balm of Christ’s love, as prototype and pattern, actually a response to a state which only offers a call to arms—with Christ, there is only a call to alms in the offence of the world (Matthew 11:6).

If you have followed me so far, my reader, you will be aware of the contours that haunt our partially ironic, partially provocative declaration for the anarchic cause. In the effort to become a Christian in a world typified by its broken Christendom, there is a constant threat that our aims can become subverted by a desire for the display of aesthetic power and the possession that our possessions might have on us. These anarchist-aesthetes, while notable in their actions and their ability to do what they said, cannot play the role of inspiration to us: indeed, not as anarchists, as Christians, or as Christian anarchists.

To navigate our way out from amongst the crowd, who would willingly allow themselves to shed their responsibility to self and other in the readiness to use violence, we shall turn to three men in particular who have stood out from the malaise of their contemporaneousness and assert what needs to be asserted: I know that it is not I who knows all.

Paul against the arkys

Of course, a fine place to start this would be scripture. Indeed, why not start with 1 Corinthians, the piece that most notably took to the task of undermining those who would erect themselves as the foundation of the world:

Where is the wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the disputer of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of this world? For since, in the wisdom of God, the world through wisdom did not know God, it pleased God through the foolishness of the message preached to save those who believe. For Jews request a sign, and Greeks seek after wisdom; but we preach Christ crucified, to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks foolishness, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. Because the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men. (1 Corinthians 1:20-25)

It is a wonder, my dear reader, how we have so long mistaken the problem of the Ancient Christian use of Plato and Aristotle as an affirmation of their content as opposed to a leveraging of their language towards his own purposes. A flit of irony, where the master’s tools are wielded against him, so to speak. Here, Paul clears away the ground on which this world—whether it be exemplified through the acts of the Greek pagan philosophers, the anarchist-nihilist, or the “play Christian” playing Christianity—wishes to erect its own plan for how things ought to be and how things ought not to be, quickly before dressing it up in the language of a greater metaphysics.

Note that Paul makes the point that, at the root of the Christian teaching lies the revelation that Christ—God Himself—was crucified and died in the form of the human subject in the midst of human society at the hands of human authority. Instead of offering us “first things” or “basic assumptions”, he makes the grand declaration which rips apart all prior, respectable thought of the serious scholar: indeed, it appears that Paul, in his impudence, is forced to revere the revealed where others would have it distorted to an object of science. The Jews, hearing this, find it a stumbling block; the Greek, hearing this, find it an exercise in foolishness. And yet—

On Pagan authority and intellectualism

Here, my reader, is where we find the radical reinterpretation of what came before within Paul’s thought that puts the bleating scoffs of “Platonist” and “pseudo-Stoic” to bed—he does not merely adopt these Greek positions in order to erect his own predilections on top of their carcasses, but rather he subverts their pre-propositional assumptions by way of abusing their language and turning their positions inside out. And, all along, leaves the language untouched, thereby allowing for him to claim the power that the syllogistic form has over the pagan muser and turn it back against its greatest proponent. For the Greek, in particular, the argument is the mode for understanding the truth of reality and, therefore, everything outside of the argument form can then be presumed to be false by this metric; however, this both fails to appreciate that there is a reality which exists outside of our perception of it, that may sit on the periphery of what we know and what we have yet to discover.

But this can only be true if one thing is presumed: that is possible to become the ground of truth (or, a foundation) that can accurately assess whether the objects of thought that float in the epistemological slush of our uninterrogated presumptions are true or false—if that even makes sense to believe. “No!”, says Paul to the Greek: only by sacrificing oneself at the altar of the self, in the quiet admission of finitude and limitedness, can we admit that there are things which may sit outside of our ability to make an assessment. Or, in short, the inconclusive nature of a Greek-style argument for the existence of a God or any particular thing at all about Christianity can show no more than that the argument doesn’t work—hence why the Corinthians, in their desirous arrogance to take the place of God as the ground of truth, have failed to understand the offense and the shock of the Crucifixion, the Incarnation, and revelation outright4.

What does it mean to look at the world and find only foolishness, as did Paul? It is to look at the world and declare that all things, without God, are impossible to understand as they are and as we should be: as individuals attempting to become selves from within the position of untruth against truth5. Only by way of God’s help in identifying us as against truth by the notion of revealing the individual’s condition from within sin against the good can we recognise the basic need to reject ourselves as the ground of truth.

Paul—Anarchist against Foundationalists

Presumably, this possibly doesn’t seem very “anarchist” or even political at all. Yet again, you probably think, my reader, the Christian anarchist has fallen into the trap of indulging in Christianisms and devotionals to the point where the leap to anarchism is a jarring shock, an arbitrary desire that has found its way onto the page. However, Paul’s protest has important practical implications that turn the fusty, abstract reading of his work by the academics and the critics—where the great sojourner, most notable for fostering the early seeds of the Christian church in his mission to be lifted up by God from his fallen condition and shown that roots can indeed function above the soil, is reduced to a “premise thinker” who has little to say beyond a set given brief6—attempts and fails to invert the man that not only strode down the road with purpose and power, but was also the one who had trailblazed ahead to reveal the path that had always been.

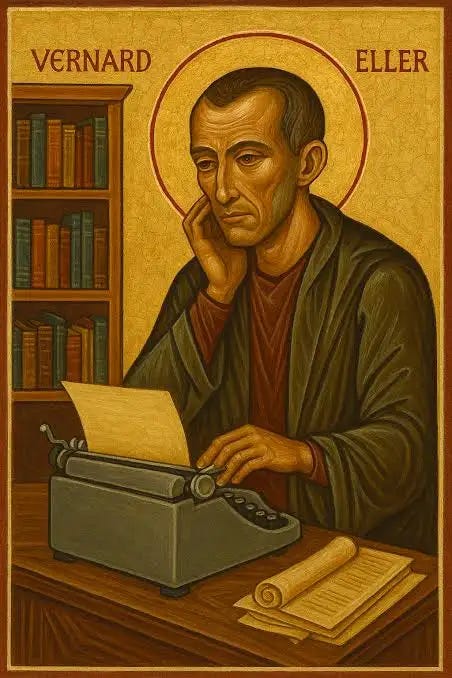

We turn to Vernard Eller, a man who saw that what Paul opposed was all arkies against the One Who “is the head of the body, the church, who is the beginning [arky], the firstborn from the dead, that in all things He may have the preeminence.” (Colossians 1:18):

“Arky faith is that enthusiastic human self-confidence which is convinced that Christian piety can generate the holy causes, programs, and ideologies that will effect the social reformation of society.”7

In our awareness that the temptation of the world, sly as it can be, can even subvert itself into seemingly holy words and sanctified deeds, Eller wields Paul against the one who will take up the Holy Mantle for his own cause: “No!”, this self-confidence, rooted in your determined grit that, above all, you are right and your neighbour shall suffer for this reason, is little more the insertion of Christ’s image into your cause in order to reach your cause’s ends. If we are to learn anything from Kant, we might say that Eller has exposed the human willingness to take the very Lord God Himself, the One Who Weeps, and made Him a means to our ends—a basic position of willful abuse of the other, let alone the One Who is “Wholly Other”. Whether Right or Left—if we are childish enough to let these cracks of the whip be enough to turn us from the path that God laid out in His blood and His love—these individuals view themselves as messianic and that they’re God’s anointed social agents of redemption.8

Eller implores us to read Paul again and again without ceasing to understand the message which turns theology from the mere expression of one’s self-confidence into a theology contra the one who believes he has forged the arky proper by his own hands. As Climacus would note, it appears that faith is “[a]n objective uncertainty, held fast through appropriation with the most passionate inwardness, is the truth, the highest truth there is for an existing person.”9 By inserting this “objective uncertainty” into our methodolgy and remembering that all “ours” are, indeed, “mine”, we find ourselves in a place where we can understand the distance between those best laid plans of vice in men and the object of their veneration—that distance, of course, being sin, the qualitative difference between man and his Maker10. This “anti-arkys” approach to theology, where we first of all and last of all reject that we are the ground of truth in all senses, leads us to the perniciously “realist” kernel of both Paul’s and S. K.’s thought: in receiving the teaching the we are first and foremost to love God and love the neighbour against the background that we, quite simply, have spent some parts of our lives not loving God and not loving the neighbour11, we can become born-again in the knowledge that Spirit has been the one taking us on this journey towards becoming aware that we are on a journey.

Kierkegaard against the arkys

When we become aware that not only is it possible for us to engage in the self-renunciation of doubt and not only is it possible for us to will to engage in the self-renunciation of doubt, then we can recognise that the fundamental need for love is the calling of our deepest desires, our primordial desire to become a self, the rooted existence that cries out to become a self before God—then we can see that, first of all and last of all, learning to become a self as God shows us is possible means learning to cast out what has already been cast out and draw in what is already drawn in for us. That thing which we are moved to do as opposed to merely decide to take up. But what is a faith that looks like this?

“Faith no longer treats Jesus as a piece of cognitive content to be studied and mastered, but as a person to whom others must have a relation. By virtue of faith, true knowledge of God and the self is first made available to a person because only through faith does a person come into relation with Jesus the source of such eternal, essential truth that sets a person free.”12

Here we come to the crumb that S. K. had left on the forest floor for us, that ingenious aesthetic frill which turns his artful prose from the mere appearance of another Christian author who had a little too much to say for themselves before they set to work into the revelation of Paul’s that rips the living individual asunder and allows for more:

“Imitation, the imitation of Christ, is really the point from which the human race shrinks. The main difficulty lies here; here is where it is really decided whether or not one is willing to accept Christianity. If there is emphasis on this point, the stronger the emphasis the fewer the Christians. If there is a scaling down at this point (so that Christianity becomes, intellectually, a doctrine), more people enter into Christianity. If it is abolished completely (so that Christianity becomes, existentially, as easy as mythology and poetry and imitation an exaggeration, a ludicrous exaggeration), then Christianity spreads to such a degree that Christendom and the world are almost indistinguishable, or all become Christians; Christianity has completely conquered—that is, it is abolished!”13

S. K. sets the challenge which brings Paul’s critique of the Corinthians into the full-blooded, full-fleshed demand of care that God has issued to humanity: if to understand is to do and if to do is to be, then it is not enough to know that Christ’s life and death—that God was born as a child, lived in poverty, and died on the cross—is the basic offense to the nihilistic malaise of antiquity, modernity, and on into the unknowable future.

Rejecting the temptation of arky-dom through participation

We must live as if that is the case before we can understand that this foolishness, this stumbling block, is actually the case. Against the romantic-idealists of his contemporary European bourgeois society, S. K. carves out a realist theology of action, a theology that tears the tolerant academics who would open up the sphere of what Christianity is so that it would include those who use its very name for untruth, that rips up the intolerant fanatic who would close down the sphere of what Christianity is so that they can reign as king supreme over their arky forged in the fires of their hatred of the neighbour—so that Christianity itself becomes a play thing, a trifle and passtime in the hands of the passive ones who do not even value their own lives enough to grasp it outright. “No!”, the cry calls, “This will not do.”

“...for the divine refuses “at any price [to] be a kingdom of this world; on the contrary, it would be that the Christian might venture life and blood to prevent it from becoming a kingdom of this world.”14

When one knows that the divine, in its “infinite qualitative difference” from humanity, rejects the very basic assumptions that humanity would make against it, the individual brought to radicalism may actually find that their most radical lashing-out against society, against the world that wrongs them, is really more of the same and a mere inversion on a theme that has haunted human history: the self-confidence to assert that I and I alone hold the keys to the kingdom that will unlock the door that obscures Christ and His salvation for us (Revelation 3:8). It appears, then, that a break from this theme would come only by way of refusing foundationalism outright—in declaring one’s uncertainty, in one’s inability to become the foundation on which the world is built. Only in the uncertainty—the objective uncertainty—of a life lived in the deliberation between what one does and what One did, does, and will do clears away the idea that we would need a ground on which to stand before we can take up the call to faith and live life as a self before God.

“Christian heroism... is to risk unreservedly being oneself, an individual human being, this specific individual human being alone before God, alone in this enormous exertion and this enormous accountability.”15

By stepping out from under the canopy of aestheticism and violence, whereby what we want is merely a thing and what we shall do is merely compel those who stand between us and that thing, we can identify the undergirding hope which breaks up the possibility of an anarchism of violence and a liberation of imposition: only by way of surrendering to the prime arkys of the universe, the One Who bears authority by virtue of His power, and through His power granted us, you and I, my reader, the power to even topple the very Great and Good Almighty Himself by way of a declaration that He doesn’t exist whatsoever16—this is the way to avoid the very danger that attractive calls to the crowd, those tempting shouts that stir the rebellious and sly mechanations of the human subject into action in the state of untruth: by becoming a self who sees, first and foremost, His God in the face of the other and the other as the neighbour who cries out to him.

And, of course, my reader, it must be noted: this willingness to join the caravan that does rove through time may extend to the willingness that we lie down and accept the world’s power in the self-sacrifice of the lamb to the secular wolf. How else could we propose such a thing but by the knowledge that vicit angus noster?17

On Malatestans and Escaping Their Trap

We have made a great deal of fuss about the need to sheer anarchism of the woolly coat of violent secular power if we are first to tread lightly enough that a phrase like “Christian anarchy” would make much sense at all. In a way, this exercise has been an indulgence to myself, a corrective against the notion that I am the rock on which I shall build my house and that maybe, just maybe, I could take up these mantles of the world—worldly politics and violence—and use them in a way which all those other silly Christians in the past had failed to do so. In the mistaken wondering as to whether it was me, really just me, who God had loved first and, therefore, I was the one to correct the alms of a scattered Christendom into a new union of Christian arms that would bring about salvation, it was always good to walk through the offense and take assessment of the ones who had fallen—secular or otherwise—at the feet of temptation and to clear away the footprints that they had left over the ones of He Who walked in freedom.

For that indulgence, I can only apologise. However, we should be sure to say that we are not quite done: firstly, we shall demonstrate where we have corrected ourselves from the path of the Malatestans; then, and only then, we shall reorient ourselves back to where we had begun and notice how this path, in the radicalness of its orthodoxy, may now appear a little different, a little more palatable, a little more walkable for those who desperately search for footprints. As is so often the case, I pray that the words of Vernard Eller do a little more to help me navigate my way out of this bind. Undergirding it all, as always, is that dialectical mastery whereby the believer’s inner relationship with God finds outer expression.18

Nachdenken against Aestheticism

First, the temptation for power:

The secular anarchist, it should be clear now, lives downstream in a genealogical chain of the would-be ethical thinkers who cannot escape their aestheticism. They are, in S. K.’s terms, the “negative unity”19 of desire and principle that arises when the unity of means and ends is divorced, when one’s aims qua consequentialist despair become frayed from one’s means qua increasingly violent isolation. Such a position, I say, my reader, is a failure to imbue the radical with the necessarily subjective: it doesn’t matter if love is recognised by all (the world will never allow for such a thing to become universal), but the lover must be able to be recognised by his fruits.20 When the anarchist, in its remoreless turn to violence, was unmasked in his shame that mere failure to be the one who would hold the crown of power was enough for him to abandon the good and view it as a temptation, it becomes clear that the apparently ethical nature of this radicalism is accidental and the aestheticism of its desire unstable21. His slavery to technique, in the Ellulian sense22, sees no possibility that the right idea might fail merely because the wrong agent or the wrong environment has not yet cleared to allow its realisation. In truth, the anarchist wishes to fail: if he does not fail, then his desire for power finally reaches the place where he could refuse power—and, with that, he ceases to be.23

This will for power, then, is one which rises up form the depths of the human agent and causes one to seize the other qua thing in an act of domination. Not only that, this act of domination is often the product, the calling card itself, of a despairing instability in the mind of the one who seizes—in an attempt to exert power, any power, into the world, it appears even the “bomb-chucker” is aware that they can assert themselves into life and history through the death of the other. But is this the life that we shall lead? Is this the freedom of Christ promised to us—bound up in the aesthetic presence of the other who is little more than the “will be dominated” to our fleeting desires?

Eller stops us short—and offers obedience, that obedience to the Word that is freely chosen, as the balm for the caustic presence of this Nietzschean will:

“If I do everything he has in mind but do it because I happen to agree that what he has suggested is the intelligent and appropriate thing to do, then in actuality I am not obeying him... this is not putting God’s kingdom and his justice before everything else; it is putting myself first, my judgements, my ideas of good and bad, of right and wrong.24

While the scoffer would like for us to think that obedience, that obedience to the Word that is freely chosen, is a surrender of freedom, it appears that it is first and foremost a freedom from this unstable desire to erect oneself as the ground of the truth, the foundation to the universe itself—that choosing to place a preeminent value on God and the God-relationship25 by way of choosing to respond to His love in the way the lover responds to the will of the beloved is itself a freedom which guards us from the temptation to use violence against the other.

But how? Obviously, Christians have been amongst those who have used violence, often under the banner of the faith. Are we merely engaging in this silly game of declaring everything I like correct! and everything I don’t incorrect!—or, as it were, electing myself to be judge, jury, and executioner on the part of the Lord? Not quite.

“The order of priority cannot be reversed; and the Christian simple life always is a positive doctrine of the enjoyment of God before it is a negative doctrine concerning the evil of the world.”26

Because, when I find faith, the faith that grips those who would have it and turns them from what they have been and makes them again into what they are and always have been, I will see that the positive enjoyment of God means that I cannot displace those Greatest Commandments: love God and love the neighbour. In the obedience to God’s Word, where I freely choose to remember that God has asked for my love and given me the tools to accept or reject it and then asked me to turn that love out into the world towards the person who calls out to me in despair qua my neighbour, I am freed from the pressure to become the ground of truth, the metric of success, or one who will clear away sin in the end of days.

In the “deferred pacifism”27 that does not allow for us to claim the authority to know that the other should be punished in the name of God and, instead, that they will be offered forgiveness and a path to salvation, we err away from claiming the other as the evidence of our power—we choose to turn the other cheek away from those temptations that drive us to think on God’s behalf (Vordenken) and, instead, take the option which would allow us to foster the seeds of healing in the soil of the sinner by way of “thinking after” (Nachdenken)28. Always, we all the hands that God uses to work in this world: and that willingness to work only with His guidance is the willingness to admit that even God may be correct when He offers the universal possibility for redemption.

The Possession of Possessions

Secondly, the temptation of ownership:

“When the object of our desire, the thing itself that either “draws” us or tempts us, becomes understood as a merely rational, a merely intellectual objective that sits in relation to some consequentialist goal or as the product of “common sense” that proceeds from whichever position the “common sense” thinker emerges from, here the danger of the will to possess and subjugate comes to the fore. When those Italian anarchists stormed into Letino and set to turning the world to their goal, their overarching aims to bring about an anarchist society through their objectivising, political mechanications were little more than an idealism given flesh—they had taken actions to allow for a “liberated” relation between subject and object, but they had not ascended beyond the need for a mere possession-relation with their objective reality.”29

Possession is often thought of within legal categories, therefore assumed to amount to a kind of contract that exists between various parties—knowingly or otherwise. However, this can’t be the mere extent of possession, because we can possess things without the law enforcing that possession. Therefore, we should recognise that there are certain things which fall into our “realm of control” which fall outside of the realm of the other and vice versa. But what does it mean for the Christian to possess something and how does that defend against this kind of power-grab where the anarchist is reduced to a moth that flutters by the burning ashes of the city he desires to see destroyed?

Eller, again, offers us a path out through his notion of “simplicity”: simplicity proper can only flow from the desire to “enjoy God”, allowing for lesser concerns to be cleared away30. Although the Christian ideal does indeed call for both the personal eschewing of wealth and the social organisation of justice in the name of worshipping God, it does not frame these things in the context of them being outright goods on their own. Taking the story of the young, rich man who speaks to Jesus, Eller notes:

“Yes, social justice, equality, and help for the poor are involved in the simple life; yet keep them where they belong, not as its motive and rationale, but as a “plus,” a gift, a freedom, a grace out of the “all the rest” that will come to you as well.”31

Christianity is not a religion of asceticism, whereby the individual can assert power over their life by way of eschewing the world around them. Indeed, such a thing seems to spit in the direction of Genesis, which takes such a strong stand on suggesting that creation is still fundamentally good—even in its imperfect nature. To eschew wealth and work for social change is not to assert those things as basic goods in a way which becomes self-referential—no, it is to express the love for God and the love for the neighbour in obedience to God’s loving commandments in a way which allows for the sloughing away of the desire for material wealth or societal authority which would undermine one’s God-relationship. In the story of the rich man, he was not being ordered to sell his possessions, but asked to sell his possessions in order to fulfil the important part: following Christ.32

From this point, our understanding of possessions, then, must become one where we are aware of how possessions can possess us and turn us away from our better interests. Instead of asserting that aesthetic desire to burn the town to the ground or to take up arms against the neighbour who sees you as the enemy, we are reminded to do one thing and one thing alone33: love God in a way which allows for that inner life to spill out into the world.

The Hegelian Sittlichkeit, parodied at length throughout S. K.’s corpus.

Violence : Reflections from a Christian Perspective, p. 21, J. Ellul

To illustrate, my reader, think about the kind people who sit at the periphery of “friend” and “enemy”, often in a warring situation: the Russian forced conscript, the Ukrainian Nazi; the reluctant IDF enrollee, the Palestinian Islamist extremist. Hopefully, my reader, at least one of these examples has raised your hackles in realisation of some “other” that sits outside of the acceptable narratives we are handed by the psychopolitical structures of our lives. If you should ever want to quickly bring a party to an end, playing your own version of this little game is usually an excellent first step on how to lose friends and alienate people. Without this presumption of a friend who wields the authority to dictate to us our enemies, though, it appears that these figures—reluctant and blameless or willing and guilty—may merely be our friends, our neighbours, who have been turned against us without reason.

“Revelation: What Forms of Authority, and to Whom?”, T. Bokedal, from Clark T & T Companion to the Theology of Kierkegaard, p. 285, ed. A. P. Edwards and D. J. Gouwens

“Paul and Kierkegaard: A Christocentric Epistemology”, H. B. Bechtol, from The Heythrop Journal 55.5 (2014), p. 944

The Religious Confusion of the Present Age Illustrated by Magister Adler as a Phenomenon: A Mimical Monograph, p. 18, [P. Minor], ed. S. Kierkegaard

Christian Anarchy: Jesus’ Primacy over the Powers, V. Eller

Ibid.

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments: A Mimic-Pathetic-Dialectic Composition - An Existential Contribution, p. 203, J. Climacus, tr. D. F. Swenson, ed. W. Lowrie

The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin, p. 95, [V. Haufniensis]

Thereby accruing the infinite debt of rejecting God’s infinite love offered to us unconditionally. Works of Love, p. 102, S. Kierkegaard.

“Paul and Kierkegaard: A Christocentric Epistemology”, H. B. Bechtol, from The Heythrop Journal 55.5 (2014), p. 954

Judge For Yourself!, p. 188, S. Kierkegaard

“Destitution of Sovereignty: The Political Theology of Søren Kierkegaard”, S. Brata Das, from Kierkegaard and Political Theology, edited by R. Sirvent and S. Morgan

Sickness Unto Death, p. 23, [Anti-Climacus], ed. S. Kierkegaard

“It is incomprehensible that omnipotence is able not only to create the most impressive of all things—the whole visible world—but is able to create the most fragile of all things—a being independent of that very omnipotence. Omnipotence, which can handle the world so toughly and with such a heavy hand, can also make itself so light that what it has brought into existence receives independence. Only a wretched and mundane conception of the dialectic of power holds that it is greater and greater in proportion to its ability to compel and to make dependent.” JP 2:1251

The Politics of Jesus, p. v, J. H. Yoder

The Simple Life: The Christian Stance Towards Possessions, p. 11, V. Eller

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 69, S. Kierkegaard

Love’s Grateful Striving: A Commentary on Kierkegaard’s Works of Love, p. 24, M. J. Ferreira

“Pacifism, Nonviolence, and the Reinvention of Anarchist Tactics in the Twentieth Century”, B. Pauli, from Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vol. IX, no. I, p. 71

The “totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.” See: The Technological Society, p. xxv, J. Ellul

“Proclamation of the Creed”, unpublished

The Simple Life: The Christian Stance Towards Possessions, p. 22, V. Eller

Ibid., p. 23

Ibid., p. 43

“Pacifism and the problem of protecting others”, H. Dexter, from International Politics, vol. 56, p. 249

Beyond Immanence: The Theological Vision of Kierkegaard and Barth, l. 2955, A. J. Torrance & A. B. Torrance

“Salination of the Deed”, unpublished

The Simple Life: The Christian Stance Towards Possessions, p. 31, V. Eller

Ibid., p. 35

Ibid., p. 33

Because, to become a self is to recognise that the will to one thing and one thing alone in the purity of heart; and, in the dialectical tension of that idea given flesh, to live the simple life is to recognise that the will to one thing and one thing alone in the purity of heart as salt amongst the world.

Have you read any Johann Hamann?