Propaganda of the Creed

For context, start here:

Christianity, whilst not entirely alien to violence, has been at the root of historical pacifist and pacifist-adjacent movements throughout all creation.

On the Eternity of the Creed

The point of departure from the secular anarchist, then, my reader, is one where we find ourselves in a different world from Errico Malatesta, Carlo Cafiero, and, even, Benjamin Pauli: we are very much in the realness of reality and posed against the adversary1 in its new, modern, contemporaneously impressive way. Now at an arm’s length from the great anarchist thinkers of early liberal society and an even further length from the great Christian thinkers of antiquity, the temptation to look back and adopt more of “the same” repackage as “the interesting” is one that could overwhelm the one not practiced in fear and trembling. The new challenge rears its head, just like the new sun rises over a new day—yet God asks for consistency from the Christian, understanding that this new sun sees nothing new under it.

There is something to be said for why these individuals failed in playing a part in God’s exodromic plan for the liberation of humanity from sin (possibly only in the sense that charges were brought against Israel’s faithlessness in Jeremiah 2) and where their worldly methods could inform—but not undergird—the Christian anarchist. Without “salt”, these efforts would always descend into the bland and flavourless architectures of domination: the very architectures that our Italian counterparts, separated by creed and time, failed to recognise in their overarching desires which undermined their goals.

On anarchist-aestheticism

For the secular anarchist, aestheticism is “the demand of the times”. The somewhat incoherent and multifaceted history of anarchist thought, constantly adopting new ideas into the bloated carcass of their political perspective as “everything is political” (especially when we interpret everything as solely political before we have encountered it in a meaningful way!), is one of constantly being invented and reinvented by some external force, some adversarial undermining factor, that takes anarchism’s sometimes tenuous foundations and rips them up with great ease. Under the pressure of the anarchist’s necessarily oppositional relation to his adversary, the pressure of negation—for example, in retrospective assessment of perceived theoretical failures or in reflective ressentiment of the world’s crushing reaction against those who oppose it—has continually led anarchists into intellectual deadends, ungrounded leaps, and outright capitulation. For one example, we turn to the “bomb-chuckers” swimming in the once surging river and now trickling stream of Malatestan thought.

Having largely abandoned the powerful insights of Proudhon into economics and sociology, the slush of theoretical musings renders itself the perfect aesthetic political position: aimed at total freedom, the secular anarchist immediately undermines their goals through their methods. In pursuit of conceptual and intellectual clarity, as a kind of intellectualist service to the oppressed, the unsettled position of the anarchist—a constant reaction against the world, constantly set in motion like a jellyfish pushed by externalities2—the thinker finds that their goals are quickly isolated from the particularities of life and abstracted into the object of consequentialist imaginings. Pulled from the state of being in which they find themselves by some desirous object that sits oh-so-tantalisingly close yet oh-so-tantalisingly far away, the aesthete is defined first and foremost by his desire for change, excitement, and “the interesting”—whatever externality draws him out into the world is whatever is good.3

With a little philosophical footwork, it is easy to see that the political aesthetic—realised in the actual—is that desire for power, the desire for the display of power which tantalises the senses, which undergirds the ambitious movements of the anarchist determined to find ground in the material. When the good, however it is defined, is determined merely by how one desires for the world to be, the methods for achieving that particular state are perilously frail: not only will the heightened desire, whatever it may be, potentially allow for any and all methods to find the blessed catharsis in which the desire is realised, but the purely immanent worldview of the secular mind doesn't allow for some greater beyond which brings about the sublime qualitative shift4.

"...mediation is not something a subject does to an object, internalizing its other and thereby overcoming its otherness. It is rather something that happens to or within the subject as it is overcome by its other."5

The ironic endpoint of the anarchist, then, is one obsessed with world domination because there is nothing else that they can aim their obsession towards: the desire for a new universal order, brought about through the particular actions of the particular agent, creates a necessarily contradictory teleology which the agent doesn’t so much strive for as merely elects the theoretically-justifiable choice of utopia from amongst the choices of utopia. Like the abstracting philosopher of old who assures us that universality and particularity are two dishes of absolute distinction and, as such, applies the logic to his menu for his soon-to-be-enlightened guests, we might wonder how success his musings are when the poor manners of one guest—failing to appreciate the value of the elected universal, possibly due to some morally relevant intellectual failing—lead to a particular anaphylactic shock from a universally-valuable peanut. Having set out to liberate the world by the way of expanding spheres of influence, both political and ideological, the anarchist turns into a variation on a theme, a coda for the individual sitting in the inconvenient “outside” of the theory’s imposed categories.6

The consequentialism of the anarchist, who, like Malatesta, Cafiero, and those following in their footsteps, means the object of the struggle, “anarchist domination”, is both contradictory in nature and also impossible to achieve—the individual anarchist has no power, within or without the collective, to ensure the success of his goals. Yet, his goals are all that he has in order to maintain his desirous steps forward, having elected the material as the totality of his theoretical bounds and those theoretical bounds being constricted by the particular life of the particular theorycrafter. This life, he thinks, is all that there is—as such, having experienced life purely as a matter of “holding back death”, as solely defined by the fear of death and death’s forgetful nature (oh so ready to forget the dead and oh so ready to help us forget them with the cathartic exhaustion of grief that buries the memory of the dead in a tearful cry into the abyss!) and, therefore, incapable of providing something that could ever be meaningful for this life. If there is some particular aim which cannot be realised within the extent of a single life, then that particular aim cannot satisfy the desire for a seemingly achievable, unachievable consequentialist end.

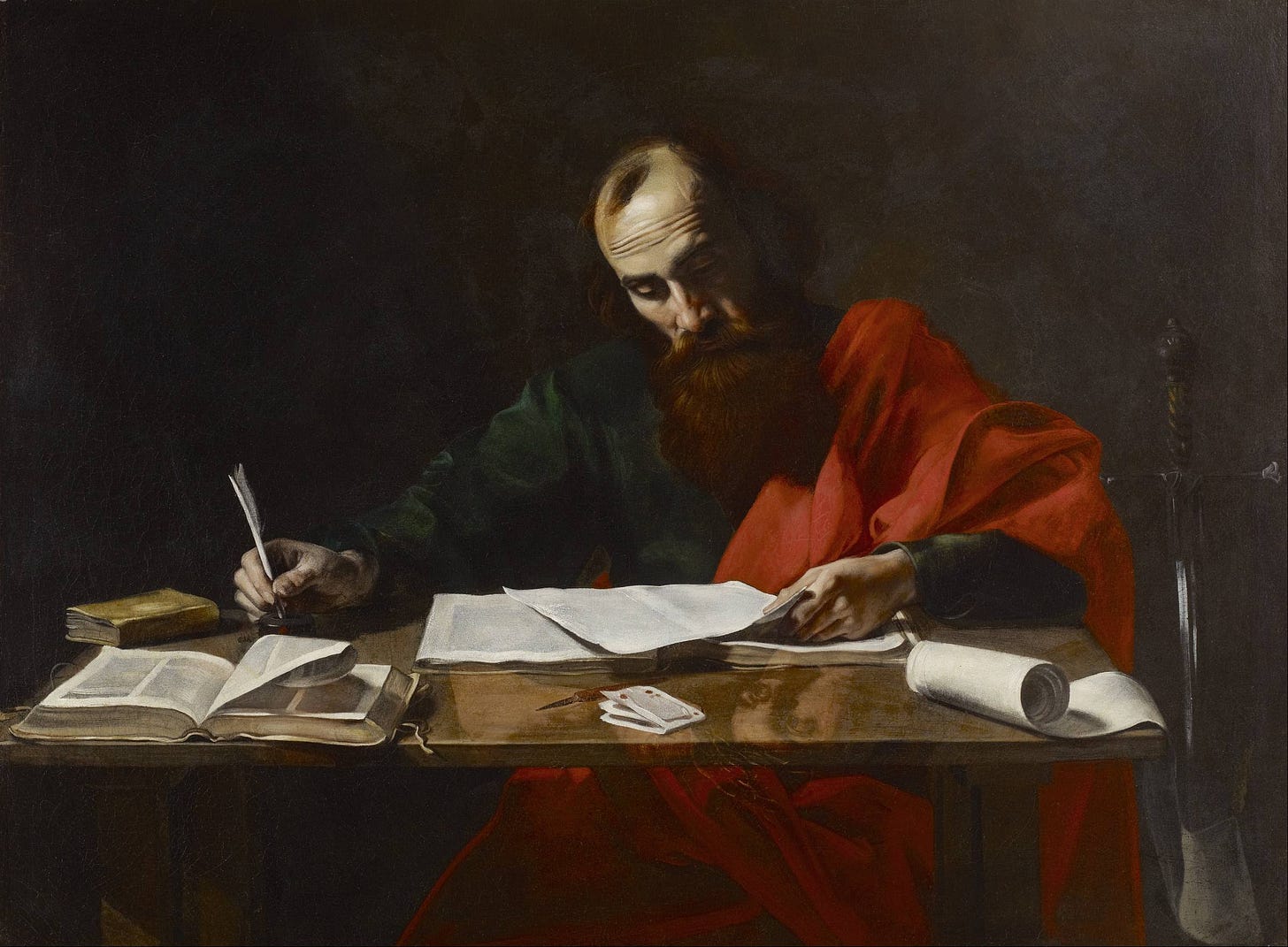

Paul against the aesthetic

However, not all is lost. The aporetic endpoint of the secular anarchist is not the dead-end that you and I, my reader, must drive ourselves into. Indeed, a man who recognised that his sin weighed on him terribly understood that the error was completely avoidable—although, not by exchanging “the aesthetic” for “the ethical”, but rather by laughing at the idea that this was the only choice available to those free in Christ.

Without the Apostle in mind, it appears that the anarchist finds himself at a standstill and unable to step forward in repetition: if the only thing that can be accounted for is biological life restricted to immanence, then life is subordinated to death.7 Whether the Malatestan method was correct or not8, the unsettling factor of reality’s imposition onto the individual, the causation of disappointed utopianism, dismisses it to the scrap pile without a second thought because—like the child, having first impressed his carers by drawing some shape that elucidates a knowing response of “square”, grins when the second, manic shape produces confusion that could only mean this drawing has outwitted them—if the theory does not immediately produce some desired affect in reality, then it must be false and it must be false for me in my life. Having presented something as if it were objective, it is dismissed with an indignant, groundless subjectivity. The crowd would laugh if it were in on the joke.

As noted by Pauli, the emergence of increasingly terroristic methods in the wake of the Malatestan revolt in 1877 shows an uncertainty, an intellectual to-ing and fro-ing, that allowed the collective strength of those radicals to dissipate into vapour. Regardless of whether they were right or wrong in their political insights—such a notion was unimportant to the unimpressed spectators, unimpressed that the consequences they had been promised had gone unrealised—the fractures appeared. Having ascended to a point of alienating terrorism, the anarchists had nowhere to turn but back against themselves. It would require a total reinvention of the position in the form of anarchist-syndicalism, and particularly the pacifist anarchist-syndicalism championed by Bart de Ligt, to give the anarchist heartbeat that had romantically pulsed throughout history some crumbs with which to rebuild itself.

While we might refuse to allow ourselves to slink away into “the ethical” and, instead, continue to recognise the danger of allowing ourselves to be tempted by “the aesthetic”, we need not fall off the wagon at this stage. In a sense, Christianity offers us an out here—one that de Ligt recognised. Despite the “pull” of Christ calling us unto Him out from over our groundless existence, we are not merely engaged in aesthetic desire; indeed, even Johannes de silentio could recognise that faith “not an aesthetic emotion but something far higher”9. The Christian has the possibility of recognising life’s existential nature, where, as a self, they step out from the ever-present, ever-potential capacity for nihilistic despair and asserts through repetition that the desire to love the neighbour, to love God’s creation, and to bear the suffering that may come—should it so come—are all fundamental, formative goods that build this fractured self from the aimless floating of the jellyfish into a Christian who sojourns. Whereas the Malatestan, concerned with worldly expansion and defining positions through signs of power over creation, is necessarily tied to the material which defines the full extent of his thought, the Christian finds that it is possible to go beyond this—that it is possible to endure through hardship and failure, even when the world shows that it is opposed to the holy; that it is possible to be a Christian, even when the world seems completely lifeless.

Even in the oppression of Letino or worse, it is possible to make a shift in thinking, a leap from one mode of thought to another: “a shift away from thinking of creation in the past tense to thinking of creation in the present tense.”10 Instead of seeing the world as something handed onto us and merely the object of our reckoning, the very goodness of creation can deliver us something that is deontological good—the genuine unity of means and ends.

“The communication is far from being the direct paragraph- or professor-communcation; being reduplicated in the teacher by the fact that he ‘exists’ in what he teaches, it is in manifold ways a discriminating art.”11

In seeing the Teacher is the teaching, the Christian is protected in his retreat into the Body of Christ: that it is possible for what one does to be good as a “movement of infinity”12 that is good qua expression of Christian character and only defined, contoured in that expression. In the deliberation between the self and the Teacher, it is possible for means and ends to be united. The world does not turn by virtue of our self-elected radicalism, but as a movement towards God and the part we might play in His plan—a plan that preceded us and will outlive us. At no point can the Christian ever make himself the centre of the universe or his politickeering the centre of his life as we must always be aware that God loved others before us, loves others besides us, and will continue to love others when we have gone.13

The tension of the in-between

The secular anarchist, it should be clear now, lives downstream in a genealogical chain of the would-be ethical thinkers who cannot escape their aestheticism. They are, in S. K.’s terms, the “negative unity”14 of desire and principle that arises when the unity of means and ends is divorced, when one’s aims qua consequentialist despair become frayed from one’s means qua increasingly violent isolation. Such a position, I say, my reader, is a failure to imbue the radical with the necessarily subjective: it doesn't matter if love is recognised by all (the world will never allow for such a thing to become universal), but the lover must be able to be recognised by his fruits.15 When the anarchist, in its remoreless turn to violence, was unmasked in his shame that mere failure to be the one who would hold the crown of power was enough for him to abandon the good and view it as a temptation, it becomes clear that the apparently ethical nature of this radicalism is accidental and the aestheticism of its desire unstable16. His slavery to technique, in the Ellulian sense17, sees no possibility that the right idea might fail merely because the wrong agent or the wrong environment has not yet cleared to allow its realisation. In truth, the anarchist wishes to fail: if he does not fail, then his desire for power finally reaches the place where he could refuse power—and, with that, he ceases to be.

My reader, remember: there is nothing new under the sun—and, yet, there are more in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in this radicalism. Before we set off, sojourning from the safety of the camp into the valley, pulled by the sublime beauty of a future not yet known, i.e., the very concern of ethics in a world which mistakes the field for abstracted calculi and exercises in imaginary probabilities, the need to “cut to the bone” and remember on whose shoulders we stand and to what we owe them. The will to drive on into the blackness of an as-yet-empty future is the realisation of that anxiety which could make the life of the bomb, the ravacholier18, all the more tempting in the face of failure, the assurance and promise that this can work as this has worked that streams forth from Christ’s twin faithfulness, first in the love for Father and then in the love with the neighbour, like a raging torrent that flows through the arteries of that individual who understands that freedom requires discipline and discipline requires responsibility. In this way—or, rather, the imitation of this way—the proclamation rings out.

When the flabbiness of aesthetic rhetoric and objective ritualism is stripped away, the core is exposed: “faith is precisely this paradox, that the individual as the particular is higher than the universal, is justified over against it, is not subordinate but superior.”19

“[“Satan” is] only the composite, the synthesis, the sum total of all the accusations brought by people against other people in the world.” If You Are the Son of God..., p. 8, J. Ellul

Kierkegaard and the Climate Catastrophe: Learning to Live on a Damaged Planet, p. 13, I. W. Holm

Søren Kierkegaard's Christian Psychology, Kindle location 1631, C. Stephan Evans

For obvious investigations into this, see the quick intensification of oppressive tactics by the “Makhnovist” tendencies in Ukraine under the shadow of the Bolshevik revolutions. While it would be an error to consider these movements to be necessarily reactionary in flavour, the hagiographic apologetics offered for Nestor Makhno by ideologues often collapses into the same comic hilarity of those who would exalt the Crusades as the height of Christian faith—a pagan error, where the omnipotent God is reduced to some entity that requires “defending”—or the well-trodden irony of priest who enjoys the sound and only the sound of the kerygma—an intellectualist error, where sermons and the like are understood to be a particular kind of lecture.

"Kierkegaard's Teleological Suspension of Religiousness B", M. Westphal, *Foundations of Kierkegaard's Vision of Community: Religion, Ethics, and Politics in Kierkegaard*, p. 111, edited by G. B. Connell and C. S. Evans

To illustrate, in a more general sense, Ellul points to the “kulaks” in the Soviet Union as an unfashionable “othered” group that refused to fit into the glorious planned society of the utopian Marxists. See Money & Power, p. 15, J. Ellul. While there are, indeed, many “othered” groups that the radical theorist might be comfortable with integrating into the palacial grandness of their thought, this selection of the “othered” leads to the creation of a “favoured oppressed” that becomes socially acceptable—or, possibly, a “virtuous” signal to the unobviously virtuous—at the behest of the socially unacceptable “unfavoured oppressed”. In some extraordinary moments, the Christian might even be tempted to advocate for violence(!) on behalf of these oppressed. See Violence : Reflections from a Christian Perspective, p. 21, J. Ellul.

“Paul Against Biopolitics”, J. Milbank, from Theory, Culture & Society 2008, p. 140

And, for the sake of those who are unsure of which side of the fence I sit on, it was incorrect.

Fear and Trembling: a Dialectical Lyric, p. 38, [J. de silentio]

“Toward a Kierkegaardian Understanding of Hitler, Stalin, and the Cold War”, C. Bellinger, Foundations of Kierkegaard's Vision of Community: Religion, Ethics, and Politics in Kierkegaard, p. 219, edited by G. B. Connell and C. S. Evans

Training in Christianity and the Edifying Discourse which 'Accompanied' It, p. 123, [Anti-Climacus], ed. S. Kierkegaard

Fear and Trembling: a Dialectical Lyric, p. 33, 93, [J. de Silentio]

“The Gift of the Church and the Gifts God Gives It”, S. Hauerwas and S. Wells, from The Blackwell Companion to Christian Ethics, p. 17, ed. S. Hauerwas and S. Wells

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 69, S. Kierkegaard

Love's Grateful Striving: A Commentary on Kierkegaard's Works of Love, p. 24, M. J. Ferreira

“Pacifism, Nonviolence, and the Reinvention of Anarchist Tactics in the Twentieth Century”, B. Pauli, from Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vol. IX, no. I, p. 71

The “totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.” See: The Technological Society, p. xxv, J. Ellul

Ibid.

Fear and Trembling: a Dialectical Lyric, p. 46, [J. de silentio]