Aside from his commitment to the Christian faith, our melancholic Dane might be best known in modern circles as a critic of “the Press”. An uncomfortable bedfellow of “the Right” in identifying the discourse-moulders, taste-makers, and trend-setters as the root of the nihilist bent of modernity, S. K. finds his critique of “the press” mixed up with a hodge-podge of semi-philosophical protests against hollow targets, themselves simply ideologically motivated to take down the wrong kind of press and not seeing the damage that such a structure in any form causes to social life and, particularly, religious faith.

His critique and influence on those existentialists who would adopt his work to obscure their own trend-setter social standings still speaks today, often obfuscated either through Heideggerian hatred1 or Sartrean groundlessness2. It is obvious to see how these filters have led to S. K.’s position in the modern conversation. Through, most notably, the curious book-review-cum-proto-sociological-deconstruction, A Literary Review, and the more conventional tracts of his “fellow-traveller” protege Jacques Ellul, such as Propaganda—if a more “on-the-nose” title could be imagined—the Christian critique of social nihilism is one that still has importance for the wandering individual in contemporary society, however. And, like those who walked before me, like those who sought to break up the meddling professional class’ groping fingers of influence, like those who imitated Paul as he has imitated Christ in the relentless destructio3 of all before them, I shall start not from a secular basis but from a Christian one:

“God is the sole bestower of grace. He wants every person (educated up to it through proclamation of the requirement) to turn, each one separately, to him and to receive, each one separately, the indulgence which can be granted to him. But we men have turned the relationship round, robbed or tricked God out of the royal prerogative of grace and then put out a counterfeit grace.”4

In the wilderness forty days, being tempted by the Press

“While in the tension of reflection the better energies keep each other in check, baseness rises to the surface, its impudence impressing like a kind of force and its contemptuousness becoming its protective privilege, because it allows it to escape envy’s attention.”5

“The Press” operates in two ways: i) by encouraging the readers to lose their “rootedness” in their own material lives and then ii) by turning these uprooted flowers of spring loose upon one another in the “vortex”—as, “without rootedness in particular problems, the individuals and groups become advocacy groups that are essentially particular sources of endless gossip”6. The chattering classes aim to whip up an audience and then whip that audience out of control—if you are well acquainted with the mainstream media, you will likely have noted multiple instances where, e.g., non-voters, third-party voters, and the like are put under pressure to conform with the demands of the political class; if you are better acquainted with the “Christian Right” on Substack, you might have noticed their theology extends to as much as “pray, eat well, and work out”, which is obviously as much as we can expect of these new Niebuhrs of our own generation.

While “the Press” was a specific object to S. K. and, no doubt, also is to you, my reader, the bigger problem is recognising that this instrumental-wielding of a “public voice” has now largely been democratised, leading to an even slushier, even more bizarre attack on the individual by those who would wield the collective against him—now, Judge Wilhelm’s reflections on Nero seem to apply to everyone7. Where once the movement from vox Dei to vox populi presented a challenge for those living in early modernity, the shift from vox populi to something far more widespread—as if we could have thought such a thing would come along!—has created a new problem that S. K. could not have imagined. However, that does not mean that he did not leave us valuable insights on which we can rest our resistance to the world—beginning, first, with “the Public Sphere”.

“Kierkegaard thought that the Public Sphere, as implemented in the Press, promoted risk-free anonymity and idle curiosity, both of which undermined responsibility and commitment. This, in turn, leveled all qualitative distinctions and led to nihilism, he held.”8

Here, we see the problem as it is—“the Public Sphere”, the destroyer of qualitative distinctions. Encompassing the actions and decisions of a particular “crowd-former”, “the Public Sphere” serves as a particular form of “the Crowd” that wants to force itself into every corner that it can reach and make our lives subject to its interest. Notionally, an element of “the private sphere” also exists, where the individual can exist without intrusion from some kind of public entity; however, in practice, this sphere is so negligible that it simply acts as a propagandistic tool for those who seek to make the most of “public opinion”.

As liberal society is based upon the creation of national consensuses, international relations, and bounded populations that can be turned towards different goals as and when they are required, the individual within liberal society might view this modern-day superstition, the existence of some kind of “public opinion” as if it belongs in uniformity with those forced into uniform, to be a necessary good of the modern liberal society. We are, after all, working together towards our collective betterment, aren’t we? Liberal theoreticians such as Richard Rorty went as far to criticise S. K.—along with Dostoevsky and Nietzsche—as presenting individualist figures which are a threat to democracy because their committed figures of action and passion, the Knight of Faith and the Overman, are “conversation stoppers” and “a disaster in the context of democratic society”9. Interestingly, we find this particular approach also embedded in the late liberal theology of the Niebuhr brothers, especially the creeping pragmatism of Reinhold, the older of the pair.10 The individual may be an individual in number, but they are still only an extension of the collective that grants them their rights—it is the legal biopolitics of modernity which precedes our relation to the world.

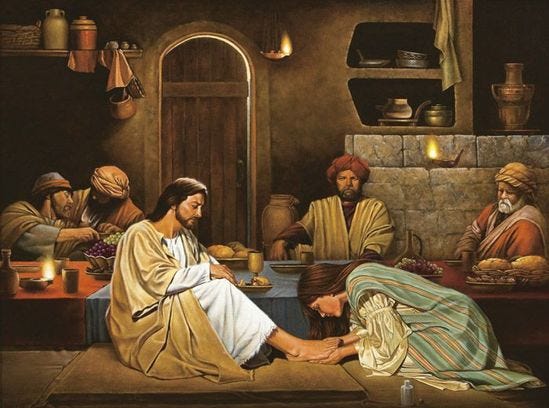

However, phenomenologically, this overlooks a considerable theological problem for our liberal theological comrades-in-alms: “the Public Sphere” is confronted as an object without substance, reminiscent of “the Crowd” in scripture (Matthew 9:23-26; Mark 2:4, 7:17; Luke 7:1-10, etc.) and the sociological works of our dear Melancholic Dane11. If God truly does “want every person (educated up to it through proclamation of the requirement) to turn, each one separately, to him and to receive, each one separately, the indulgence which can be granted to him”, then how can this happen when “the Public Sphere” crushes us under the weight of the seemingly abstract object of public opinion, herd mentality, and social pressure? Unlike the apparently innocuous and innocent “private sphere” of life, “the Public Sphere” is tyrannical in that it demands obedience, piety, and willful co-operation. The ideality of the legal structures that haunt modernity precede reality—we are expected to take these impositions as sociologically more basic than the relations between those at hand. It attempts to capture the “God-function” without offering anything that God actually holds for us12. “The Crowd” is whipped up into a frenzy, placing it against the Christian ideal—the individual who lives in the liberty of the body of Christ.

“In fact, if the daily press, like some other occupational groups, had a coat of arms, the inscription ought to be: Here men are demoralized in the shortest possible time, on the largest possible scale, at the cheapest possible price”.13

As the mouthpiece of “the Public Sphere”, “the Press” is the knot around which it revolves. Unlike the Marxists, however, who simplistically relate “superstructual” components of society with particular class interests and (if we are to extend this analysis to degenerated forms of Marxism) power relations, S. K. viewed “the Press” as taking on an opportunistic and unloyal role within the struggles that are necessary within the world. While “the Press” may well represent capitalist class interests whenever it is most suitable for both parties—and, pragmatically, it is fairly obvious why this is; it is in the corporate interest of a media corporation to get into bed with those who can actually fund further corporate existence—it can also turn and twist to new avenues whenever it is most beneficial to maintaining its semi-class role within a particular social situation. Regardless of who “the Press” falls in line with, however, it serves as a negative force within society that attempts to destroy any possible positive claims for how people ought to live—even if these only extend as far as traditional rationalisations which recognise the debt we might owe to those came before us. The negative interaction with “the Public Sphere” completely negates any and all values that the individual holds—regardless of what the individual might think when rooted in their particular social nexus, the media attempts to intercede any real social relation and subvert it towards its own ends because community must always make way for the “pseudocommunity”14, man must be recreated in the image of the new “demand of the times”. Reality must bend a knee to the demands of ideality; to suggest otherwise is treason against “the Idea”—to ensure that ideality reigns supreme, “the Press” operates obscuring the line between the two in a wave of language.15 Here, conventionally, the “Right” has had something to say about the matters at hand, but this has rarely extended beyond grumbling that they do not control the narrative or—even worse—snivelling self-victimisation. In either respect, there is a distinct childishness to their approach that falls short of the demands of Christianity; regardless of their effectiveness, there seems to be no scriptural basis for soundlessly begging for cancellations to stop.

Where is “the Left”?

The problem here for “the Left” is simply a matter of embarrassing guilt. Having outed the liberals as hypocrites and liars (as all agents of “the world” will eventually be discovered to be), they simply took up the master’s tools and set to work with their uncritical adoption. The anarchists, the Marxists, the “left-liberals” and the “progressives”16 are complicit in the development of this “professional-activist” caste within our modern-day societies, where “the one” finds themself thrust into a leadership position for the scrambling masses.

Of course, the problem of the scrambling masses is that they are a creation of this circular process: the engaged individual has certain obligations and wants relating to the immediate world around them (family, local politics, work, etc.) which is undermined by the forced “zoomed out” global perspective. This then leads to a certain groundlessness of trying to see the world from the God’s eye view. Much as God is suspended by seemingly nothing at all, the individual in the liberal democratic society finds themself out on the “70,000 fathoms of the deep”17 and attempts to find a light by which all other lights can be illuminated. The objective view of the world, the “view from nowhere”, the process of running away from our concrete subjective existence, leads to a rootlessness that tears the individual from any and all possible grounds—and, of course, these are by no means certain grounds—for meaning. But who is to blame for this sensation? Where do we point the finger?

As with “the Press” at large, the “Old Left”—by whom I mean the likes of Kropotkin and Marx—were members of the intellectual class and made their money through the emergence of mass media publishing. Any critique of “the Press” quickly becomes a critique of these titans of “Left-facing” thought; any attempt to exonerate them leads us into a pathetic18 display of favouritism that is as unjustified as it is idealist and as unimpressive as it is unconvincing. To turn on journalists, publishers, and “thought-leaders” is to turn on the professional class—and to turn on the professional class is to turn on the mainstays of “Left-facing” thought that planted the breeding grounds for progressivist nihilism and not-quite-post-modernist charlatanry. This is why, even when there have been attempts to undercut these themes within secular circles, the thinkers have been pushed aside and delegitimized by the faithful amongst the ranks. For a notable example from history, we might turn to the maligned Malatesta, an anarchist operating in the shadow of Prince Kropotkin. Reflecting on the Italian’s life, Levy writes:

Like the Russian populists, he sought to declass himself and go to the people, and he feared and detested the development of a class of left-wing professional journalists, orators, and politicians who fed off the social movements and betrayed their principles.19

This has been a problem for many “Left-facing” individuals since that point; an embarrassing admission, something to be kicked under the rug. The “one-another” behaviours20 of seeming pro-social movements21 are immediately replaced by the “Left-facing” propagandist’s want to mould and modify the behaviours of those around them towards a particular telos—anarchist utopia, Marxist revolution, or similar. This utopian tendency is found, ironically, in one who makes the double error in dealing with history: firstly, by failing to understand how their current condition is handed to them by the contingencies that preceded them, and secondly, by failing to understand that they are not bound to any particular future simply because these contingencies exist—after all, they are only contingent and not necessary.

The concrete wants of particular subjective existences, i.e., in the lives of the moral agents that are subjected to this assault and corraled into “the Crowd”, are undermined by appeals to eccentric and esoteric universalist moral claims (which, for the Marxist, are wrapped up as if they were not moral claims at all). Here, we find the contradiction of this particular approach to ethical thought—in attempting to establish these ethical norms, the journalist provides the universalising voice to the water-trending, globalized individual, ripped from their social fabric; the particular problems of their particularity are forced into irrelevance, allowing, unaccountably, for this cosmopolitanised individual to forget that they have a concrete existence in a concrete location and a concrete time and instead to become an expert on Soviet bureaucratic structure, Chinese financial planning, or postcolonial psychoanalysis. The individual ceases to exist, “born again” in the image of his chosen “radicalism”.

The process has worked to perfection: by drawing upon the rootlessness of the liberal subject in modernity, “the Press”—whether it is notionally “Left-facing” or “Right-facing”— rebuilds man in its image.

Sanders and the Press’ Raging Maw

While the good Kierkegaardian will always insist that “Christianity is indifferent toward each and every form of government; it can live equally well under all of them”22, this does not mean that there are no specific challenges that particular forms of government and society can bring to the would-be faithful in the faithlessness of “the world”. S. K. saw “the Crowd” as that particular challenge, the social realisation of the “vortex” of internalised lawlessness—something which we might possibly still say is the problem to this day. As evidence of that, in lieu of providing an example from this current spin of the vortex, can be found in Sanders’ attack on the establishment (ironically, from within the wings of the establishment) covered by Politico here.

Bernie Sanders, once the beacon in the darkness for now disaffected right-wing talking heads and, incomprehensibly, the political second-coming identified by more than a handful of Marxists, came out against the politicized media (or, “the media”) by setting his sights on the Bezos-owned Washington Post. A more general assessment of Sanders’ particular political position at this point is uninteresting—prioritising the speck here instead of the plank would be as intellectually interesting as it is theologically justified, so we will pass over that until we feel slightly more bored and slightly less concerned with saying something interesting. Sanders drew ire from the Washington Post by saying:

“I talk about that all of the time… And then I wonder why The Washington Post — which is owned by Jeff Bezos, who owns Amazon — doesn’t write particularly good articles about me. I don’t know why. But I guess maybe there’s a connection. Maybe we helped raise the minimum wage at Amazon to 15 bucks an hour.”

Fighty.

As one can imagine, the Emporer does not like having his new clothes exposed to the unwashed masses—they, in their unwashedness, when simple dialogue cuts across the enforced dialectic23, would be better served if they could remain reduced to the nothingness that “the Press” requires in order to operate. The aforementioned ire first arose from Baron, the editor under attack:

“Sen. Sanders is a member of a large club of politicians — of every ideology — who complain about their coverage,” Baron said in a statement. “Contrary to the conspiracy theory the senator seems to favor, Jeff Bezos allows our newsroom to operate with full independence, as our reporters and editors can attest.”

And the response from within the Sanders’ camp:

“The hyperoverreaction from many in the media to Senator Sanders’ critique reveals a bias,” Sanders’ campaign manager, Faiz Shakir, wrote in an email. “There is a sneering, contemptuous disdain that infuses those comments and a willingness to put words into Bernie’s mouth that he just didn’t use.”

My reader, stay with me here—obviously, we are witnessing the various arms of “the Press” scratching at one another. However, this fight within the ranks of the establishment shows that “the Press”, laying its own gizzards before us, is openly exposing class interests here. And, despite the Post’s denial of this problem, here we stand years later, staring down the barrel of Bezo’s actualised threat. Reality runs up against ideality again and now a new ideality is constructed to spin the vortex towards new goals.

Christ contra the Raging Maw

Any secular examples of this will always rely on identifying some kind of hypocritical agent which has discord to sow towards some particular political end. This is simply a matter of fact when it comes to “the world” in modernity. Even here, by broaching “the political”, the temperature is turned up and simple dialogue becomes difficult—we must draw upon propagandists in order to even access the hypocrisy within the ranks. If we were to rebuke either side, the mechanisms of modernity attempt to draw us into the dialectic and insist we take a side—which, of course, means becoming a member of “the Crowd”. This is not a free choice, but a structural one; this is not an intellectual response, but a coerced one. So, from where does the Kierkegaardian speak?

In understanding that we are always under the threat of becoming a slave to the proclivity of “the world” (John 8:33-35), Christians have a special duty. Not a duty as in the slavish impositions of the Law onto others or the terrified doubt of falling back into world-slavery, but rather in presenting the freedom that comes in walking with Christ. However, this is a rather difficult to understand—what does it actually mean to been known by fruits? S. K. never moved from his position that, at its most basic, this is related to the anxiety of existence, as first described in detail by Vigilius Haufniensis:

“[A]nxiety is the dizziness of freedom that emerges when spirit wants to posit the synthesis, and freedom now looks down into its own possibility and then grabs hold of finiteness to support itself.”24

I will let you chew over this short excerpt in your own time, my reader—our emphasis here is that important phrase: “the dizziness of freedom”. Anxiety presents itself to us in the moment where we must choose, we must turn to the universe and make a movement that moves from us. But what is the condition of the person forced into making a choice by reality?

“The prohibition makes him anxious, because it awakens in him freedom’s possibility.”25

To meet the Law is to have the Law judge one; we are pushed into the same situation as Adam and Eve in Genesis 3:6-8: we are presented with a choice, an either/or, between whether to obey or to be left to anxiety. Note here that this condition of the anxious uncertainty of the confused mind is the exact feeble creation that “the Press” wishes to create—wrapped up in Indesluttethed [“shut-upped-ness”]26, the individuals cannot identify a genuine relation to the world around them; they are thrown from pillar to post, corraled by the loudest voice that appeals to empty concepts such as “saving democracy,” “making great again,” and the utterly idiotic obsession of “being on the right side of history.” It almost seems silly to wonder what these people think because they seem to lack any thoughts whatsoever when “the Crowd” rolls out its sloganeering. In this haze, the crushing weight of the Law and the obedience it demands is the only freedom from the anxiety of choice—a break must be applied to the vortex’s velocity, a harsh “no!” that brings a stop to the chatter.

If there is a contradiction drawn between the Law and freedom, then we have failed to understand what is being said: there is no contradiction at all because in complete obedience to God's Law, the individual becomes “free to achieve the simplicity and singleness of his own authentic existence.”27 The anxiety of choice that “the Press” would shove us into, would hold over us like a holy judgement, is not forced upon us at all when there is a committed system of ethics to which we hold fast. The intellectual, embarrassingly confident in his ability to differentiate and delineate a seemingly endless onslaught of intellectual propaganda, hops from argument to argument as if it is commendable to evidently have no opinion about the world that would bring one to obstinately oppose certain notions—open-mindedness being the clarion call of those who see ethics and metaphysics as curious puzzles to solve, not real investigations with real applications and real consequences. Through the commitment to God, we are not corralled into believing that the proletariat (or, rather, the idea of “the proletariat”) is the engine of history; we are not strong-armed into thinking that salvation comes from overthrowing governments to form a commune (or, rather, the idea of “the commune”); we are not promised safety from within the confines of a freed market (or, rather, the idea of a “free market”) which provides all our needs for as long as we keep government interference out. We are held aloft by the promise that God will grant salvation to those who seek salvation from Him:

“For Christians, the matter is clear: the law is no longer a duty. It is there to give indications, for we singularly lack imagination and boldness for action.”28

There is no essential character to the Christian life—it is an existential promise, a journey that we are called to, which offers us freedom from within the Law. The indicators of God’s “no!” to humanity reveal the genuine liberty that emerges when one uncovers the “yes!” behind it. But this, of course, is not simple.

Standing Alone—With the Help of the Other!

The child who has the comfort to automatically turn to his mother after the toils of the day, safe in the knowledge that their decision to go out and play, to listen to music, to draw the things that come to their imagination, to ride a bike, to climb a tree, to indulgence in indulgent Romantic imagery, and possibly even remember to say a prayer or two—this child is always safe in the knowledge that they have been given their tasks for the day by another, safe in the knowledge that someone looks over them and guides them through their days in order to stave away that “dizziness of anxiety”, that terrible looming threat of choice. “Behold, children are a heritage from the LORD, the fruit of the womb a reward. Like arrows in the hand of a warrior are the children of one’s youth” (Psalms 127:3-5), an expression of the freedom of Christ when one has someone to guide the way through the darkness, to point the path ahead when it might seem obscured. But the adult, the grown individual who knows that “the Good” is, who do they turn to? They do not have this freedom from choice—if anything, the anxiety of freedom marks the difference between the child and the grown adult because the latter is always aware that they could, in a situation where a choice is demanded, always choose freely. Their choices offer them no salvation from despair, but instigate it; their choices are not free like the child’s, but the object of competing desires—holy, demonic, and everything in between. Their choices carry responsibility to the self, to God, and to the other. The child turns to their master when there is a need for guidance. What are we to do? Where are we to turn?

“Shall I seek to secure a position that corresponds to my abilities and strengths, so that I can be effective in it? No, you shall first seek God’s kingdom. Shall I give all my fortune to the poor, then? No, first you shall seek God’s kingdom. Shall I go out and proclaim this teaching to the world, then? No, you shall first seek God’s kingdom.”29

In S. K.’s own language, the adult who says the right things, goes the right places, and seemingly lives the right kind of life (an essentially Christian life—what a thought! A life more essentially Christian than Christ’s, no doubt.) but does not seek God’s kingdom starts from a position of autocracy—the arkys faith of the sovereign individual against the world. This, often presented as some kind of ideal by a particular flavour of Protestant Americanism, is the fundamental disbelief that God works amongst us. This solitary person, as are all people, is terribly frail alone—a single stick underfoot in the forest, fooled into thinking that it is strong because it lies close by to other sticks; a single rabbit in the field, under the talon of the falcon flying overhead, fooled into thinking that it is strong because it nestles amongst other rabbits in the field; a single person in “the Crowd”, broken by batons, fooled into thinking that it is strong because it stands with other people in direct danger. “The Press”, with jaw agape, stalks its prey by spinning the great-many into “the Crowd”—the individual without grounding, fooled into thinking that they are safe, finds that they have abandoned themselves by asserting their self-mastery by attempting to wrestle their lives from their Master. “[T]he adult is simultaneously master and servant; the one who is to command and the one who is to obey are one and the same”30, which means that the choices the adult makes matter—but will they turn to themselves, reflexively relating to their physical existence, as if it were not something that is infinitely frail? Do we trick ourselves into thinking we cannot die at any moment, for any reason, “when death comes, the word is: Up to here, not one step further; then it is concluded, not a letter is added”31? Or do we accept that we must die to the world, accept that we are frail and in need of God-leadership—in need of a master who we must choose?

Here, we find the differentiation between S. K.’s concepts of Religiousness A and Religiousness B: the choice to find rest in Christ is one which calls the believer to inaction, to doubt, to Nachdenken. While a certain type of hot-headed faith might drive one to relentlessly launch accusations and judgements against the world might attract plenty of attention, it can be a cover for the kind of liberal theological thought that represents Christianity as a particularly intricate sequence of syllogisms or an aspect of a system—in modernity, we might even view Creationism to be a modern expression of this, where Christianity (or, really, Genesis 1-11) is reduced to a historical and/or scientific theory. To avoid shifting over the various problematic implications, in short: liberal theology presents theology as if it is only worthy inasmuch as it can kill another field of inquiry and wear its skin. As with all skin-wearing, however, all this does is expose the skin-wearer as something not to be trusted. By falling back into the security of mathematics with Descartes, of philosophy with Hegel, or of the scientific method (applied in an unusual way) with Ham, these theologians admit that God must gain authority from somewhere—somewhere we actually afford authority, because it obviously isn’t afforded to theology itself. Our choice to have faith is forced down, forced to hide behind the actual authority—the authority that no one would doubt!—of another mode of inquiry. It is not our fault that we believe this: anyone with eyes to see and ears to listen would believe such a thing if only they understood maths or philosophy or science in the proper way! Like the intellectual, faith becomes a plaything for the other to show us; it is an immediacy that meets us where we are and politely accepts us as we are—stuck in the techniques of the age, with the conventions of the age untouched. It lacks the willed response to follow when there is no contingent system of logic supporting the necessary truth that cuts across it. “No!”, we say; we have chosen to follow God above what we are into what we will be. We willingly accept the task to find that which “I cannot do otherwise, God help me”32; we accept the independence of becoming an adult in faith by learning “to stand by oneself - through another's help!”33 The person who cannot take this leap will find that their head can be turned with a sufficiently popular and sagacious argument, so why bother talking about these outdated ideas of transcendence and volition? Why should we first seek God’s kingdom if, instead, all we need is the correct proof?

“The Press” has no power over the faithful because first they shall seek God’s kingdom. There is no need to be drawn into the danger of anxiety, the danger of choice, when the person begins first by choosing to follow God. There is no platform that “the Public Sphere” can erect that turns us towards its own ends—because there is no platform that could summarize the message of God’s self-revelation. And this message, in all of its bustling existence, love of creation, and love for the other, cannot be reduced to a theory amongst theories, propaganda amongst propagandas, or a proof amongst proofs. “The Public Sphere” cannot touch God’s revelation because God calls neither the atomised individual nor “the Crowd” to worship—He calls the concrete existing individual, in the caravan with his fellow travellers. The nihilism of mathematical, philosophical, or scientific(!) proofs for God’s existence—especially stomach-turning when presented from a place of “no presuppositions”, as if such a thing were possible—is the final hurdle for the faithful to recognise that their lives themselves point towards God, towards Christ, and towards the neighbour who reaches out to us in their need. To recognise the face of the weeping God in the other and to be washed in love when the leap appears to us is faith. And, from there, we begin our ethical journey—not a theory!—and our political action—not a platform!—that shows fruits to the world.

In the final subversion of all categories, the Lord gives us nowhere to turn, but we must find that nowhere through the choice to turn to Him—and in that cul-de-sac, we find freedom.

“A poet has told of a youth who on the night when the year changes dreamed of being an old man, and as an old man in his dream he looked back over a wasted life, until he woke in anxiety New Year's morning not only to a new year but to a new life.”34

Søren Kierkegaard's Christian Psychology, Kindle location 825, C. Stephan Evans

“Kierkegaard and the Relativist Challenge to Practical Philosophy”, P. Mehl, from Kierkegaard After MacIntyre, p. 4, ed. J. J. Davenport and A. Rudd

The Political Theology of Kierkegaard, p. 31, S. Brata Das

JP II 1476

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 73, S. Kierkegaard

“Dreyfus on Kierkegaard and the Web”, p. 1, F. M. Dolan

“Melancholy and Modernity”, C. B. Barnett, p. 179, from Kierkegaardian Essays: A Festschrift in Honour of George Pattison, ed. C. Carlisle and S. Shakespeare

“Kierkegaard on the Internet: Anonymity vs. Commitment in the Present Age”, by H. L. Dreyfus, from Kierkegaard Yearbook, 1999, p. 96, edited by N. J. Cappelørn, et al.

“Kierkegaard in the Context of Neo-Pragmatism” by J. A. Simmons, from Kierkegaard's Influence on Philosophy - Tome III: Anglophone Philosophy, p. 184, ed. J. Stewart

As critiqued in The Peaceable Kingdom: A Primer in Christian Ethics, S. Hauerwas

E.g., Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 11 S. Kierkegaard; “On My Work as an Author” in The Point of View, p. 9, S. Kierkegaard; The Religious Confusion of the Present Age Illustrated by Magister Adler as a Phenomenon: A Mimical Monograph, p. 14, [P. Minor], ed. S. Kierkegaard

The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air, p. 37 S. Kierkegaard

JP II 489

Christian Anarchy: Jesus' Primacy over the Powers, V. Eller

“Immediacy is reality; language is ideality; consciousness is contradiction [Modsigelse]. The moment I make a statement about reality, contradiction is present, for what I say is ideality”. Johannes Climacus, or, De Omnibus dubitandum est, p. 168, [J. Climacus]

I place the final two categories here with heightened scepticism, viewing them not as genuine “Left-facing” fellow travellers but consistent historical enemies of the disenfranchised, the poor, and the meek—while the Marxist is the propagandist par excellence and the anarchist his less successful little brother, those who openly preach “progressivism” are best understood as nihilists and wreckers representing the same PMC class that “the press” draws its power from.

Works of Love, p. 363, S. Kierkegaard

In both senses of the word.

Life and Ideas: The Anarchist Writings of Errico Malatesta, Kindle location 67, forward by C. Levy, ed. V. Richards

Potential Christian examples of these include James 5:16; Hebrews 3:12-13, 10:24-25; 1 Thessalonians 5:11; Colossians 3:16; Romans 12:15; and Matthew 18:15-18, as identified in The Radical Wesley: The Patterns and Practices of a Movement Maker, p. 200, H. A. Snyder

Although it would be improper to reduce Christianity to a “social movement”, an ethical theory, or some kind of political tendency, there is a certain analogy that you, my reader, should be able to identify here.

JP IV 4191

Propaganda: the Formation of Men's Attitudes, p. 6, J. Ellul

The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin, p. 61, [V. Haufniensis]

Ibid., p. 39

Ibid., p. 124

Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship, p. 161, V. Eller

“The Bible and Christian Action”, J. Ellul, tr. L. Richmond, from Jacques Ellul and the Bible: Towards a Hermeneutic of Freedom, Kindle location 1147, ed. J. M. Rollinson

The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air, p. 25, S. Kierkegaard

“The Gospel of Sufferings: Christian Discourses”, from Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, S. Kierkegaard, p. 294

"At a Graveside", from Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions, p. 78, S. Kierkegaard

Works of Love, p. 78, S. Kierkegaard

Ibid., p. 275

“At a Graveside”, from Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions, p. 76 S. Kierkegaard