If you want to find further reflections on Christian anarchism and taxation, see S. K.’s thoughts here:

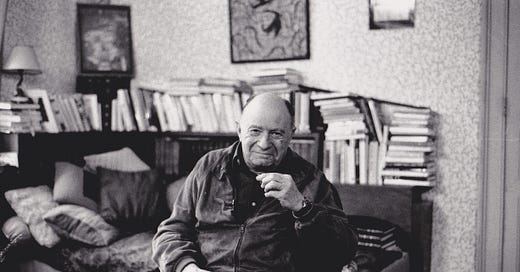

Jacques Ellul was an unusual thinker with an unusual intellectual background which made him a far more eccentric thinker than this scholar of law and society would have us first imagine. Drawing from Kierkegaard, Marx, and Barth1, Ellul also wedded his Calvinism with a radical sense of free will and the socio-political reflections of his fellow countryman Pierre-Joseph Proudhon to arrive at an explosive theo-sociology which questioned our relationship with technology, explored the radical politics of Christ’s indifference, and attempted to build a community of the faithful within the shell of the old world. A full exploration of this man’s life would require books upon books, so, my reader, we will leave this embarrassingly short biographical sketch here for the moment. I will no doubt attempt a more elaborate hagiography in the future for dear St. Jacques2.

As the most prominent example of a Christian anarchist who does not collapse into an inverted, socially acceptable form of Constantian arky-faith, Ellul’s reputation often proceeds him. In no small part, this may also be due to a particularly infamous anti-technology thinker drawing heavily from Ellul’s debut work3. As with Kierkegaard’s influence seeping through into the Nazi thought of Hirsch, Heidegger, and Schmitt, Ellul’s own influence on the violent tactics of Uncle Ted really shows us that stripping these thinkers of their theological foundations does tremendous harm to their bodies of work and teeters on the irresponsible from the second it is proposed. In an effort to illustrate the distance between Ellul and his radical, misguided false disciple, we shall turn to one of the very first issues Ellul considered in defence of his fullest exploration of Christian anarchism: Mark 12:13, render unto Caesar4.

The “money problem”

Ellul, like all good Kierkegaardians, was bitingly dialectical and unwilling to fall in line with either the main waves of conservativism or radicalism within his own time. While identifying with a broadly “Left” approach, he refused to join with the Marxists (following a similar political line to another one of his heroes, Karl Barth, who supposed it was unthinkable that anyone would mistake the Soviet Union for presenting a Christian solution to the problems of the 30s and 40s5) and was refused entry to the Situationists on the grounds of his Christian faith—having myself experienced similar with a notable anarchist-syndicalist organisation, my reader, we might wonder how far we have progressed from the sectarianism of the early 20th century!

As such, Ellul turned to Christ and Kierkegaard in order to establish something new: a movement of the Christian anarchists.

Christian anarchism - a third position

Perceptive of “the Crowd” and “the Anti-Crowd” of his time, i.e., the capitalist police state and its adherents in “kulaks” against the communist police state and its adherents in “system-builders”6, Ellul was keen to avoid the errors of both the “vulgar economists” who push everything into being a problem for the particular individual and also the responsibility-undermining objectivity of the Marxists and other systematic cultural critics who push everything into being a problem for the wider society—forcefully in the stinging first chapter of his Money & Power7, where no one from the lumpen thief to the capitalist dictator8 is left without critique. The key was to avoid falling into the problem of viewing economic matters as solely subjectively or objectively; much like S. K.’s view of ethics, love, and faith, Ellul did not see the life of the individual as possibly divisible from the wider sociological context of their existence—but this context did not absolve the individual from responsibility for their particular actions within it!

“Personal money problems are a thing of the past: I don’t need to worry about who I am or what I do because I support a system which answers for everything, is the key to all difficulties, and will solve for all humankind every problem that I come up against personally.

To solve the problem of money by joining a system is to choose an

alibi which allows me, in all good conscience, to remain uncommitted... But all this activity is a justification for avoiding personal decision making. My money? My work? My life? I don’t have to worry about them because I am involved in such-and-such a movement which will take care of all that for everyone once it comes to power. This escape hatch gives me an enormously easy way to avoid facing reality and realizing the power money has over me.”9

Here we broach the “money problem”. What is a view of money that escapes both the aestheticism of the vulgar economist and the objectivity of an ideologue?

Whenever we talk about money, we always end up by asking. How should we organize the economy?—or even, What economic system should I support? “At the moment,” we explain, “I may not be using money the way I should, but when the new system (whatever it may be) is instituted, when the general money problem is solved, I in turn will become just.”

Thus we subordinate moral and individual problems to the collective problem, to the total economic system. If a man is a thief, it is not his fault; his economic conditions were such that he could be nothing else. Let us beware. If we accept this excuse on behalf of a poor person, we must accept it for everyone. Both the capitalist who exploits workers and the farmer who dabbles in the black market are also involved in impersonal economic conditions which leave them no options. As soon as we accept the supremacy of global concerns and of the system, as soon as weagree that material conditions remove our freedom to choose, we absolve all individuals of all responsibility for their use of money.

Seen in this light, how can capitalism be more valid than communism, or communism than capitalism? The same error lies at the heart of both : the flight from responsibility and the pursuit of an alibi.10

From this perspective, it is clear that Ellul’s Christian anarchism is neither “right-anarchism” in the tradition of Tucker and Rothbard nor “left-anarchism” in the tradition of Bakunin and Kropotkin—any attempt by the Christian to hide in the irresponsibility of championing either capitalism or socialism is to choose someone before God. If we are going to present a Christian account, we must begin with the idea that this is not a secular position because a determinant should be discarded if doesn’t actually determine anything 11. So, surely, Ellul’s view of tax will be a matter of finding the individual within the object of mass society—which can only lead us to conclude that tax resistance could be appropriate, correct? This perspective could potentially reduce the problem to a matter of conscience, not theology.

A “Left-er” perspective—without essentialism

While Marx and the anarchists that emerged within the period of the formidable German’s intellectual greatest influence can be considered anti-essentialist in many ways, aiming to turn away from such high metaphysics that would stand in the way of social change and liberation, there is a strange dogmatic immovability within the ranks about the need to abolish money. For some like Kropotkin, this was a matter of utmost urgency, with the social catastrophe of revolution allowing for a rapid reorganisation of society which is fundamentally rational and based on a want for the common good12; for others like Marx, this would be a gradual process as money specifically and the “money-form” more generally would be phased out within the movement from “the lower stage of communism” to “the higher stage of communism”13—whatever that might look like.

If we are charitable to Marx, this is due to the special importance that he placed on alienation in the capitalist economy14 and the way that money acts as a “point of separation” through commodity fetishism15; the social reality is replaced by a reified system of economic exchange that “hangs over” society, meaning that genuine sociality replaced with transactional relationships and a dehumanisation of the other qua the means by which I acquire commodities which fulfil my particular consumerist ends. This, in turn, identified radical politics of consumption, i.e., radical thought rooted in the position that we simply stop consuming certain commodities, as ineffectual towards the goals of revolutionary change as the alienation of commodity fetishism forces the proletariat to partake in commodity exchange—telling the proletariat not to buy products xyz does about as much as telling the drug addict we can solve the social ill of addiction by simply consuming half as much fentanyl.

Whether we agree with Marx or not here is irrelevant—indeed, a Kierkegaardian assessment of commodity fetishism is due. What we should understand here is that Ellul did not hold to this particular view of money. Instead, he rejected that money is evil (or, at least, an impediment to social change) per se on two grounds: i) the relationship between humanity and wealth can’t be simply understood as a two-way relation, but as a broader three-way relation16, and ii) despite the popular image of wealth being detestable emerging from the New Testament, this is not the only image of wealth within the Biblical texts. In his usually brutish manner, Ellul quite simply says that money is how economies function and it isn’t obvious that we can have complex economies without it; to suggest otherwise, without invoking the “myth of human perfectability”17, might be reactionary in the worst kind of way and imply that we go back to the gift economies of the indigenous family on a mass societal level—reactionary here because it is simply “unethical to the ethical” to imply such a thing could obviously happen. Unless we plan to dehebraicize Christ and scripture, the Old Testament must be addressed as well—through Abraham, Job, and Solomon, we see a positive account of wealth that still doesn’t call us to become capitalist hoarders18. Only when we understand Ellul’s view of wealth can we understand his perspective on taxation.

Wealth and detachment

Firstly, Ellul was keenly aware that the use of money was very different in the ancient world compared to today. He understood that, “[l]ooking at money from a purely naturalistic viewpoint (which we must do if we want to understand the prevailing world view), we no longer seem responsible for our money, how we earn it or how we spendit, for in the impersonal interplay of the economy, we are quite insignificant,”19 which was obviously different from the state of things in Christ’s time where money was, if nothing else, certainly not a fiat currency. “It is untouchable; the individual can do nothing about it. We each get our share of money. We spend it. What else can we do? If things do not go well, the most we can hope for is a change in the economy. And indeed, if money is an economic reality tightly linked to the social complex, what can we as individuals do when we see injustice, imbalance, disorder? In the presence of such an enormous machine, the individual act can hardly be taken seriously.”20 As with so much of Ellul’s writing, we’re justified to think that maybe the hope we hold is necessarily against all hope.

However, this hopelessness is only perceived—using the illustration of Abraham, Job, and Solomon, Ellul addresses the often-unpopular-in-“radical”-circles viewpoint that wealth is not rejected wholesale in the Old Testament. Indeed, wealth is praised as a gift from God!21 If we were the kind of Christians who view natural theology as an appropriate way to approach Christianity, we might even conclude that wealth is a concrete identifier of blessings in the Old Testament. Of course, we’re not like that as we are good theologians. And, as good theologians, we should hold Abraham in dialectic with Christ.

Abraham - the holy rich man!

Much to the offence of the usual “Left” readings of the Bible and much to the (misguided) relief of the “Right” readings of the Bible, Abraham is portrayed as a man of considerable wealth. In being blessed by the Lord, he takes the best of his wealth and prepares to embark on a journey based solely on his faith in God (Genesis 12:5) of which, after “quarreling arose”, he gave half to Lot—enough to sustain a small community (Genesis 13:6-17)! To do that requires extensive wealth, to say the very least; but, of course, this is not criticized at all in the text. Maybe we should think twice about the seemingly obvious faithlessness and spiritlessness of the Prosperity Gospel and the American secular religion more generally, my reader.

Considering the literary economy of scripture, we might consider this an interesting omission, especially when Abraham is continually praised as the paragon of faith otherwise. Ellul notes:

“[Abraham] separates from Lot in order to avoid strife, leaving his nephew free to choose the best land. Against the natural law which would give him precedence, he gives Lot first choice. He subordinates himself without paying attention to his own need to find pasture for his flocks. In actual fact, Lot takes the richest land, and Abraham puts up with the desert and the mountains.

And as he renounces wealth Abraham receives God’s promise concerning this land. Because he gave up his right of first choice and the foundation of his fortune, Abraham is given the whole land. “All the land which you see I will give to you and to your descendants for ever” (Gen 13:15). This wealth is not only material. Neither is it actual.”22

Here, Ellul drives ahead of S. K. in terms of the power of his critique: wealth is not only material and neither is it actual. In the story of Abraham’s grand journey, still only in the first steps out into the desert and beset with quarrels, we find a faithfulness in God that rises above all other values—including money. Abraham, in his supererogative care for his nephew, does not allow wealth or the love of wealth to become an issue that separates the faithful from his neighbour; regardless of what else comes, God will care for us. The wealth, then, is not simply the material gifts from God that Abraham had brought on his adventure into the ethical-religious following, but it is also the assurance from God that there is wealth that transcends over both the actual and the material. But this isn’t the only time when Abraham faces the temptation to surrender his piety in the struggle with wealth—in Genesis 14:21-24, the King of Sodom tempts our heroic simple man of faith:

Now the king of Sodom said to Abram, “Give me the persons, and take the goods for yourself.”

But Abram said to the king of Sodom, “I have raised my hand to the Lord, God Most High, the Possessor of heaven and earth, that I will take nothing, from a thread to a sandal strap, and that I will not take anything that is yours, lest you should say, ‘I have made Abram rich’— except only what the young men have eaten, and the portion of the men who went with me: Aner, Eshcol, and Mamre; let them take their portion.”

Abraham encounters “the powers” that Christ similarly warned us against and identifies the very thing which turns the messily abstract concept of power into the concrete: the transfer of wealth. The snake in the grass is identified in the avoidance of the threat and the indifference is displayed in response: the faithful should not become compromised by their dealings with the world lest the world demand the faithful forget the genuine power in which they are faithful—as Christ affirms and intensifies in Matthew 5:33-35, an oath, the promise to the other who would supplant God, is a temptation for the faithful. As Abraham clearly showed and Christ clearly preached, the Christian should be aware of the insipid faithlessness in uttering the words “I swear by Almighty God…” or “I pledge allegiance…” in that the individual reduces God to pleading for the authority to be God from the secular powers—a thematic knife that S. K. was all too willing to twist in the side of the Christian who had decided that sola fide implied to the exclusion of works!23

Wealth simpliciter, my reader, as such cannot be viewed as holy. Abraham’s anarchism, contra the Prosperity Gospel, here is two-pronged and directly informs Ellul’s understanding of the Christian teaching concerning taxation:

Wealth is a gift from God: its mere existence is not, despite the appearance it has to the contemporary “Left”, obviously evil—it is a tool with which we can turn to the world and offer riches in our will to share the love of God with creation. But to do that, a detachment from wealth is essential.

Wealth is a temptation to escape our responsibilities as Christians: by submitting to “the powers” in the exchange of wealth, the Christian becomes compromised and in danger of holding wealth as key to their very existence. Whether this means resisting the temptation to take money or to resist paying what one might owe is irrelevant as the problem is simply rooted in the priority of one’s obligation to wealth itself ahead of the duty to God.

The “childishness” of tax resistance

And that brings back us to the matter of taxation. In the grand scheme of things, Ellul did not depart too far from S. K.’s thought—how could he? It would mean to depart from Christ, something very much not in the interest of our unusual Marxian-Calvinist professor. But, of course, bear in mind that Ellul held a particular view of wealth as not necessarily evil—this should be added to the arsenal of our reflection. Although Ellul’s assessment of his anarchist perspective on taxation is varied within Anarchy and Christianity, we will only deal with his two points of discussion relating to Christ: Mark 12:13 and Matthew 17:24.

We begin with Mark:

“The enemies of Jesus were trying to entrap him, and the Herodians -put the question. Having complimented Jesus on his wisdom, they asked him whether taxes should be paid to the emperor: "Is it lawful to pay the taxes to Caesar or not? Should we pay, or should we not pay?" The question itself is illuminating. As the text tells us, they were trying to use Jesus’ own words to trap him. If they put this question, then, it was because it was already being debated. Jesus had the reputation of being hostile to Caesar. If they could raise this question with a view to being able to accuse Jesus to the Romans, stories must have been circulating that he was telling people not to pay taxes.”24

As was so often the case with our French troublemaker, he perfectly captures the drama and peril of the situation: Christ is being cornered by “the enemies” (a theme also emphasised in Luke 20:20). The question does not exist outside of a political context—Christ was caught between both apologists for Rome and zealots against her. Yet, with a deft turn, he undermines the dialectical tension of the question and refuses to become complicit or revolutionarily committed to the opposition:

As he often does, Jesus avoids the trap by making an ironical reply: “Bring me a coin, and let me look at it.” When this is done, he himself puts a question: “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” It was evidently a Roman coin… The mark was the only way in which ownership could be recognized. In the composite structure of the Roman empire it applied to all goods. People all had their own marks, whether a seal, stamp, or painted sign. The head of Caesar on this coin was more than a decoration or a mark of honor. It signified that all the money in circulation in the empire belonged to Caesar. This was very important. Those who held the coins were very precarious owners. They never really owned the bronze or silver pieces. Whenever an emperor died, the likeness was changed. Caesar was the sole proprietor. Jesus, then, had a very simple answer: “Render to Caesar that which is Caesar's.” You find his likeness on the coin. The coin, then, belongs to him. Give it back to him when he demands it.25

Again, this Kierkegaard-like perspective of indifference emerges in the reading of Christ: this obviously belongs to Caesar, so give it back to him! Why would I want to hold this coin as important to me when it is marked for someone else? Take it and “render unto Caesar what is his!”—with the second phrase of the couplet undermining the power of the question that “the enemies” have posed. Money is robbed of its mammonic qualities in this moment—instead of seeing the value of appealing to Rome alongside “the enemies” or viewing tax resistance as a viable mode by which one could oppose Rome, Christ views it as an object amongst objects. This has his seal, it obviously belongs to him, so give it to Caesar. It is about as interesting, especially from a theological perspective, as a toy bearing the name of its child owner.

With this answer Jesus does not say that taxes are lawful. He does not counsel obedience to the Romans. He simply faces up to the evidence. But what really belongs to Caesar? The excellent example used by Jesus makes this plain: Whatever bears his mark! Here is the basis and limit of his power. But where is this mark? On coins, on public monuments, and on certain altars. That is all. Render to Caesar. You can pay the tax. Doing so is without importance or significance, for all money belongs to Caesar, and if he wanted he could simply confiscate it. Paying or not paying taxes is not a basic question; it is not even a true political question.26

Without taking a side, Christ has deflated the issue from its apparent dramatic and perilous beginnings. Ellul goes beyond this implication, however, to remind us to become contemporaneous with Jesus: Christ came as a theological solution to a theological problem, refusing to become politicized unnecessarily by the workings of “the enemy”—we should do the same by remembering that although there are political elements to many things (including, obviously, Christianity), not everything is political and, as such, not everything requires a political response27. To suggest such a thing would be a category error.

And so, the Christian anarchist can become contemporaneous with Christ and remember the indifference and obstinacy that the “third position” of our political theology allows us: Caesar could always just confiscate the money if he wished even if it “belongs” to you, so Christ took no time to entertain the idea that tax resistance could lead to the Kingdom—because the government can always just seize it anyway, so paying or not paying taxes is not even a proper political question for the Christian (or possibly anyone at all!). As such, the idea that tax resistance could be a positive Christian action—even in the knowledge that Christ specifically saw no importance in such a tactic—is an effort to remove our responsibility from actual theologically sound political action, or, as S. K. put it, an escape into “childishness”. Turning to tax resistance is to break the law for the sake of breaking the law; it has no theological purpose, no virtuous goal, so it should be abandoned as a tactic which can have no possible relation to the coming of the Kingdom.

Ellul strengthens us:

On the other hand, whatever does not bear Caesar's mark does not belong to him. It all belongs to God. This is where the real conscientious objection arises. Caesar has no right whatever to the rest.28

And now, onto Matthew:

We read in Matthew 17:24ff. that “when they came to Capernaum, the collectors of the halfshekel tax spoke to Peter and said, ‘Does not your teacher pay the half-shekel tax? Peter responded, ‘Yes.’ And when he came into the house, Jesus said to him, ‘What do you think, Simon? From whom do the kings of the earth take tribute or taxes? From their own sons or from foreigners?’ Peter answered, ‘From foreigners.’ Jesus then said to him, ‘The sons are thus free. However, not to scandalize them, go to the lake, cast your line, and take the first fish that comes up. Open its mouth, and you will find a shekel; take that and give it to them for me and for yourself.’”

This is truly one of the stranger sequences in the gospel: Christ, in a moment of aristocratic obstinacy, invokes the miraculous to a seemingly trivial end. Firstly, we might suggest that this shows that God has a sense of humour—when placed in situations of ridiculous political attempted crowd-formation, the Lord undermines the very thing that the world demands from Him. The dialectical tension between the seriousness of the Old Testament and Christ’s good news is a point of interest here. However, that is not the end of the story. Ellul continues:

Jesus first states that he does not owe the tax. The halfshekel tax was the temple tax. But it was not simply in aid of the priests. It was also levied by Herod the king. It was thus imposed for religious purposes but was taken over in part by the ruler. Jesus claims that he is a son, not merely a Jew but the Son of God. Hence he plainly does not owe this religious tax. Yet it is not worth causing offense for so petty a matter, that is, causing offense to the little people who raise the tax, for Jesus does not like to cause offense to the humble. He thus turns the matter into a subject of ridicule. That is the point of the miracle. The power which imposes the levy is ridiculous, and he thus performs an absurd miracle to show how unimportant the power is. The miracle displays the complete indifference of Jesus to the king, the temple authorities, etc. Catch a fish - any fish - and you will find the coin in its mouth. We find once again the typical attitude of Jesus. He devalues political and religious power. He makes it plain that it is not worth submitting and obeying except in a ridiculous way. One might object again that this was no doubt possible in his day but not now. At the same time it was an accumulation of little acts of this kind which turned the authorities against him and led to his crucifixion.29

Ellul invites us to consider the possibility of turning the concept of radical politics around completely—from revolution to obstinate non-co-operation. In holding fast to the imitatio Christi, although we are obviously unable to perform such miracles, we can absolutely adopt the same tactic: indifference and sarcasm in the face of the would-be authority. The anarchist theological view of money becomes key: wealth has no theological weight, so the idea that it does should be met with the exact derision it deserves. It would be asking something ridiculous and ill-thought-out of the Lord, much like scanning the text for a justification for military service.

This is key to understanding Ellul’s overall anarchist reading of Christ’s life: in attempting to gain authority over the God-Man, a simple moment of the unexpected unveils an obstinate temperament that not only places Christ in opposition to the state but also places Him alongside the poor—all of the poor. Regardless of who is presenting the case on behalf of the powerful (and bearing in mind that the particular tax collectors are not the Kierkegaardian “one” who attempts to wield “the Crowd”, but rather a worker simply attempting to get by30), the poor and oppressed are spared from Christ’s insolence. While the individual representative of “the Crowd” is certainly held as a moral agent avoiding their moral agency by both Ellul and S. K., the target to shatter is the leader, “the one”, the individual that has the power to whip up the “vortex” in the confusion present within the malleable crowd below them. Christ looks beyond the agent of “the one” and, in an act of political indifference, pays the tax in the most absurd way—by telling Peter to pull the halfshekel from the mouth of a fish, any fish, to put an end to the absurdity. Christ pays the tax as a ridiculous request: have your money, even when it is unjust to request it from the other; regardless of your absurdity, the money shall have no power over the Lord. While we cannot call forth currency from the mouths of fish, we can certainly adopt this indifference and refusal to accept that a tax could ever have priority over God.

Tax is simply wealth

In this twin exploration, first of Abraham, then of Christ, we see Ellul’s lightning-sharp analysis of tax resistance and its implications on the life of the Christian. Despite doing the impossible—building a Christian political approach from scripture!—we have found that tax resistance is simply not an anarchist action for a few reasons. Ellul guides us:

Wealth is to be shared not simply because it is moral to share what we hold, but because wealth can never be prioritised over the obligation to God or to the neighbour.

Wealth is not to be dealt with lightly for fear that it offers the other power over us—either directly or indirectly—that pulls us away from actual moral behaviour.

Wealth, despite it being a gift from God, is not free from the temptation of “the enemy”—if they insist that the wealth we hold belongs to them, let them have it!

The absurdity of taxation can sometimes be leveraged over in order to undermine us—but resisting this actually draws us into the grasp of “the powers”.

In a capitalist economy, resisting these factors can be extremely difficult. Some, such as Kropotkin, viewed them as impossible31. However, his dismissal was based on consequentialist grounds—something far too embarrassing for the Christian to base their thought upon. As Johannes de silentio correctly identified, my reader, consequences have a bad habit of coming after moral behaviour—as such, to base a moral decision on consequences is to base our choices on the non-existent, the necessarily outside of our control, to be “unethical to the ethical”. However, what S. K., Ellul, and Christ called us to do, before all, is simply to have a change of heart, to will towards metanoia; “seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added to you” (Matthew 6:33). With the detachment from wealth, the ironic understanding of taxation, and the “turned-aroundness” of faith, we can do something far greater than tax resistance: the deprioritization of wealth—but not as a teleological, political aim, but rather as the natural byproduct of the prioritization of God through Christ. We rob money of its demand on us that we absolutely relate to it absolutely.

And with that, Jacques Ellul has given us the keys to the Kingdom.

“But we must bear in mind that Christians are not required to do this [decide between capitalism and socialism which is the proper economic mode for Christianity], and that in any case this is not true commitment. To believe that joining a movement is the same as committing oneself is simply to capitulate to today’s sociological trends, and it is to follow the herd while claiming to make free choices. Better to judge the herd instinct beforehand and give in to it only when it is objectively valid, as we are trying to do here; otherwise we are in exactly the situation described by St. Paul: “children, tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine” (Eph 4:14). It is painful to see countless Christians in this situation.”32

If you enjoyed this deliberation, see S. K.’s thoughts here:

Kierkegaard Renders Unto Caesar

Taxation. A fundamentally stateful problem, one that has forced individuals from various perspectives and walks of life to contend with the cost-benefit analysis of seemingly unconsented seizure of earnings by an official body of some sort, it is no surprise that it plays a prominent part in both the history of anarchism and the gospel itself. While tho…

An intellectual heredity which the author, my reader, also confesses to some extent—accounting for the useful addition of Ellul himself, of course.

As with semi-ironic references to Kierkegaard as “St. Søren” by the likes of Hirsch and Wittgenstein, my appraisal of Ellul as saintly in his own right should be understood as only said with a teasing yet affectionate tone of which he would have disapproved. I like to think that he would approve of my intention to worm out his disapproval.

The Technological Society, J. Ellul

Anarchy and Christianity, p. 59, J. Ellul

Theologians Under Hitler, p. 18, R. P. Ericksen

Money & Power, p. 15-16, J. Ellul

Ibid., particularly p. 9-19

Admittedly, simply another example of a thief.

Money & Power, p. 16, J. Ellul

Ibid., p. 11-12

“When all are Christians, Christianity eo ipso does not exist”, from The Instant, no. 5, July 27th 1855, from Attack upon "Christendom", p. 166, S. Kierkegaard—in this case, my reader, we might consider that when all ethical frameworks are secular, Christianity eo ipso does not exist for the opposite reason.

“Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles”, from Kropotkin's Revolutionary Pamphlets, p. 59 P. Kropotkin, edited by R. N. Baldwin

Critique of the Gotha Programme, p. 10, K. Marx

Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, p. 29-30, K. Marx

Capital, vol. I, p. 47-53, K. Marx

Money & Power, p. 47, J. Ellul

Ibid., p. 15

Ibid., p. 36-42

Ibid., p. 10

Ibid., p. 11

Ibid., p. 37

Ibid.

“Is the State justified, Christianly, in misleading the people, or in misleading their judgement as to what Christianity is?” from The Instant, no. 3, June 27th 1855, from Attack upon "Christendom", p. 132, S. Kierkegaard

Anarchy and Christianity, p. 59, J. Ellul

Ibid., p. 59-60

Ibid., p. 60

“Kierkegaard on Politics: Putting the Modern State in its Place While Loving Our Neighbours”, p. 53, J. J. Davenport, from Truth is Subjectivity: Kierkegaard and Political Theology, ed. S. Walsh Perkins

Anarchy and Christianity, p. 60, J. Ellul

Ibid., p. 63-64, emphasis mine

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age–A Literary Review, p. 76-77, S. Kierkegaard, ed. A. Hannay

“Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles”, from Kropotkin's Revolutionary Pamphlets, p. 56 P. Kropotkin, edited by R. N. Baldwin

Money & Power, p. 23-24, J. Ellul